Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things (6 page)

Read Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things Online

Authors: Charles Panati

Tags: #Reference, #General, #Curiosities & Wonders

The wedding cake was once tossed at a bride as a symbol of fertility. The multitiered confection is a French creation

.

Thus, the throwing of shoes, rice, cake crumbs, and confetti, as well as the origin of the wedding cake, are all expressions for a fruitful union. It is not without irony that in our age, with such strong emphasis on delayed childbearing and family planning, the modern wedding ceremony is replete with customs meant to induce maximum fertility.

Honeymoon: Early Christian Era, Scandinavia

There is a vast difference between the original meaning of “honeymoon” and its present-day connotation—a blissful, much-sought seclusion as prelude to married life. The word’s antecedent, the ancient Norse

hjunottsmanathr

, is, we’ll see, cynical in meaning, and the seclusion it bespeaks was once anything but blissful.

When a man from a Northern European community abducted a bride from a neighboring village, it was imperative that he take her into hiding for a period of time. Friends bade him safety, and his whereabouts were known only to the best man. When the bride’s family abandoned their search, he returned to his own people. At least, that is a popular explanation offered by folklorists for the origin of the honeymoon; honeymoon meant hiding. For couples whose affections were mutual, the daily chores and hardships of village life did not allow for the luxury of days or weeks of blissful idleness.

The Scandinavian word for “honeymoon” derives in part from an ancient Northern European custom. Newlyweds, for the first month of married life, drank a daily cup of honeyed wine called mead. Both the drink and the practice of stealing brides are part of the history of Attila, king of the Asiatic Huns from

A.D

. 433 to 453. The warrior guzzled tankards of the alcoholic distillate at his marriage in 450 to the Roman princess Honoria, sister of Emperor Valentinian III. Attila abducted her from a previous marriage and claimed her for his own—along with laying claim to the western half of the Roman Empire. Three years later, at another feast, Attila’s unquenchable passion for mead led to an excessive consumption that induced vomiting, stupor, coma, and his death.

While the “honey” in the word “honeymoon” derives straightforwardly from the honeyed wine mead, the “moon” stems from a cynical inference. To Northern Europeans, the term “moon” connoted the celestial body’s monthly cycle; its combination with “honey” suggested that all moons or months of married life were not as sweet as the first. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, British prose writers and poets frequently employed the Nordic interpretation of honeymoon as a waxing and waning of marital affection.

Wedding March: 19th Century, England

The traditional church wedding features two bridal marches, by two different classical composers.

The bride walks down the aisle to the majestic, moderately paced music of the “Bridal Chorus” from Richard Wagner’s 1848 opera

Lohengrin

. The newlyweds exit to the more jubilant, upbeat strains of the “Wedding March” from Felix Mendelssohn’s 1826

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

.

The custom dates back to the royal marriage, in 1858, of Victoria, princess

of Great Britain and empress of Germany, to Prince Frederick William of Prussia. Victoria, eldest daughter of Britain’s Queen Victoria, selected the music herself. A patron of the arts, she valued the works of Mendelssohn and practically venerated those of Wagner. Given the British penchant for copying the monarchy, soon brides throughout the Isles, nobility and commoners alike, were marching to Victoria’s drummer, establishing a Western wedding tradition.

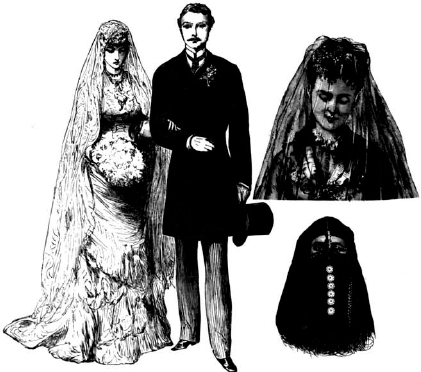

White Wedding Dress and Veil: 16th Century, England and France

White has denoted purity and virginity for centuries. But in ancient Rome, yellow was the socially accepted color for a bride’s wedding attire, and a veil of flame-hued yellow, the

flammeum

, covered her face. The bridal veil, in fact, predates the wedding dress by centuries. And the facial veil itself predates the bridal veil.

Historians of fashion claim that the facial veil was strictly a male invention, and one of the oldest devices designed to keep married and single women humble, subservient, and hidden from other males. Although the veil at various times throughout its long history also served as a symbol of elegance and intrigue, modesty and mourning, it is one article of feminine attire that women may never have created for themselves.

Originating in the East at least four thousand years ago, veils were worn throughout life by unmarried women as a sign of modesty and by married women as a sign of submissiveness to their husbands. In Muslim religions, a woman was expected to cover her head and part of her face whenever she left the house. As time passed, rules (made by men) became stricter and only a woman’s eyes were permitted to remain uncovered—a concession to necessity, since ancient veils were of heavy weaves, which interfered with vision.

Customs were less severe and formal in Northern European countries. Only abducted brides wore veils. Color was unimportant, concealment paramount. Among the Greeks and the Romans by the fourth century

B.C

., sheer, translucent veils were the vogue at weddings. They were pinned to the hair or held in place by ribbons, and yellow had become the preferred color—for veil and wedding gown. During the Middle Ages, color ceased to be a primary concern; emphasis was on the richness of fabric and decorative embellishments.

In England and France, the practice of wearing white at weddings was first commented on by writers in the sixteenth century. White was a visual statement of a bride’s virginity—so obvious and public a statement that it did not please everyone. Clergymen, for instance, felt that virginity, a marriage prerequisite, should not have to be blatantly advertised. For the next hundred fifty years, British newspapers and magazines carried the running controversy fired by white wedding ensembles.

The veil was a male invention to keep women subservient and hidden from other males. A bride’s white wedding ensemble is of comparatively recent origin; yellow was once the preferred color

.

By the late eighteenth century, white had become the standard wedding color. Fashion historians claim this was due mainly to the fact that most gowns of the time were white; that white was

the

color of formal fashion. In 1813, the first fashion plate of a white wedding gown and veil appeared in the influential French

Journal des Dames

. From that point onward, the style was set.

Divorce: Antiquity, Africa and Asia

Before there can be a formal dissolution of marriage, there has to be an official marriage. The earliest extant marriage certificate was found among Aramaic papyri, relics of a Jewish garrison stationed at Elephantine in Egypt in the fifth century

B.C

. The contract is a concise, unadorned, unromantic bill of sale: six cows in exchange for a healthy fourteen-year-old girl.

Under the Romans, who were great legal scholars, the marriage certificate mushroomed into a complex, multipage document of legalese. It rigidly stated such terms as the conditions of the dowry and the division of property

upon divorce or death. In the first century

A.D

., a revised marriage certificate was officially introduced among the Hebrews, which is still used today with only minor alterations.

Divorce, too, began as a simple, somewhat informal procedure. In early Athens and Rome, legal grounds for the dissolution of a marriage were unheard of; a man could divorce his wife whenever like turned to dislike. And though he needed to obtain a bill of divorce from a local magistrate, there are no records of one ever having been denied.

As late as the seventh century, an Anglo-Saxon husband could divorce his wife for the most far-flung and farfetched of reasons. A legal work of the day states that “A wife might be repudiated on proof of her being barren, deformed, silly, passionate, luxurious, rude, habitually drunk, gluttonous, very garrulous, quarrelsome or abusive.”

Anthropologists who have studied divorce customs in ancient and modern societies agree on one issue: Historically, divorce involving mutual consent was more widespread in matrilineal tribes, in which the wife was esteemed as the procreative force and the head of the household. Conversely, in a patrilineal culture, in which the procreative and sexual rights of a bride were often symbolically transferred to the husband with the payment of so-called bridewealth, divorce strongly favored the wishes and whims of the male.

Birthdays: 3000

B.C

., Egypt

It is customary today to celebrate a living person’s birthday. But if one Western tradition had prevailed, we’d be observing annual postmortem celebrations of the

death

day, once a more significant event.

Many of our birthday customs have switched one hundred eighty degrees from what they were in the past. Children’s birthdays were never observed, nor were those of women. And the decorated birthday cake, briefly a Greek tradition, went unbaked for centuries—though it reappeared to be topped with candles and greeted with a rousing chorus of “Happy Birthday to You.” How did we come by our many birthday customs?

In Egypt, and later in Babylonia, dates of birth were recorded and celebrated for male children of royalty. Birthday fetes were unheard of for the lower classes, and for women of almost any rank other than queen; only a king, queen, or high-ranking nobleman even recognized the day he or she was born, let alone commemorated it annually.

The first birthday celebrations in recorded history, around 3000

B.C

., were those of the early pharaohs, kings of Egypt. The practice began after Menes united the Upper and Lower Kingdoms. Celebrations were elaborate household feasts in which servants, slaves, and freedmen took part; often prisoners were released from the royal jails.

Two ancient female birthdays are documented. From Plutarch, the first-century Greek biographer and essayist, we know that Cleopatra IV, the last

member of the Ptolemaic Dynasty to rule Egypt, threw an immense birthday celebration for her lover, Mark Antony, at which the invited guests were themselves lavished with royal gifts. An earlier Egyptian queen, Cleopatra II, who incestuously married her brother Ptolemy and had a son by him, received from her husband one of the most macabre birthday presents in history: the slaughtered and dismembered body of their son.

The Greeks adopted the Egyptian idea of birthday celebrations, and from the Persians, renowned among ancient confectioners, they added the custom of a sweet birthday cake as hallmark of the occasion. The writer Philochorus tells us that worshipers of Artemis, goddess of the moon and the hunt, celebrated her birthday on the sixth day of every month by baking a large cake of flour and honey. There is evidence suggesting that Artemis’s cake might actually have been topped with lighted candles, since candles signified moonlight, the goddess’s earthward radiance.

Birthdays of Greek deities were celebrated monthly, each god hailed with twelve fetes a year. At the other extreme, birthdays of mortal women and children were considered too unimportant to observe. But when the birthday of the man of the house arrived, no banquet was deemed too lavish. The Greeks called these festivities for living males

Genethlia

, and the annual celebrations continued for years after a man’s death, with the postmortem observances known as

Genesia

.

The Romans added a new twist to birthday celebrations. Before the dawn of the Christian era, the Roman senate inaugurated the custom (still practiced today) of making the birthdays of important statesmen national holidays. In 44

B.C

., the senate passed a resolution making the assassinated Caesar’s birthday an annual observance—highlighted by a public parade, a circus performance, gladiatorial combats, an evening banquet, and a theatrical presentation of a dramatic play.

With the rise of Christianity, the tradition of celebrating birthdays ceased altogether.

To the early followers of Christ, who were oppressed, persecuted, and martyred by the Jews and the pagans—and who believed that infants entered this world with the original sin of Adam condemning their souls—the world was a harsh, cruel place. There was no reason to celebrate one’s birth. But since death was the true deliverance, the passage to eternal paradise, every person’s death day merited prayerful observance.

Contrary to popular belief, it was the death days and not the birthdays of saints that were celebrated and became their “feast days.” Church historians interpret many early Christian references to “birthdays” as passage or birth into the afterlife. “A birthday of a saint,” clarified the early Church apologist Peter Chrysologus, “is not that in which they are born in the flesh, but that in which they are born from earth into heaven, from labor to rest.”

There was a further reason why early church fathers preached against celebrating birthdays: They considered the festivities, borrowed from the

Egyptians and the Greeks, as relics of pagan practices. In

A.D

. 245, when a group of early Christian historians attempted to pinpoint the exact date of Christ’s birth, the Catholic Church ruled the undertaking sacrilegious, proclaiming that it would be sinful to observe the birthday of Christ “as though He were a King Pharaoh.”