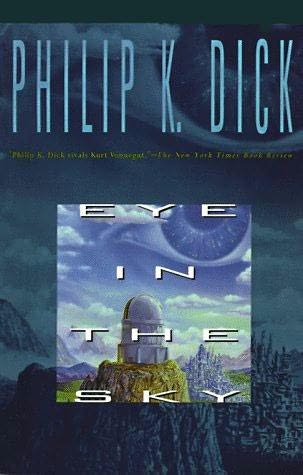

Eye in the Sky (1957)

EYE IN THE SKY

by

PHILIP K. DICK

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places,

and incidents

are either the product of the

author’s imagination or are used

fictitiously. Any resemblance to events

or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright (c) 1957 by A. A. Wyn, Inc.

First published by Ace Books

All rights reserved. No part of

this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means,

electronic or

mechanical, including

photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system,

without permission in writing from the Publisher.

Collier Books

Macmillan Publishing Company

866 Third Avenue

, New York, NY 10022

Collier Macmillan Canada, Inc.

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dick, Philip K.

Eye in the sky/Philip K. Dick.—1st Collier Books ed.

p.

cm.

ISBN 0-02-031590-2

I.

Title.

PS3554.I3E9 1989

813’.54—dc20 89-9949

CIP

First

Collier Books Edition 1989

10

98765432

Printed in the United States of America

I

THE PROTON BEAM DEFLECTOR

of the Belmont Bevatron

betrayed its

inventors at four o’clock in the afternoon of

October

2, 1959. What happened next happened instant

ly. No longer adequately

deflected—and therefore no longer under control—the six billion volt beam

radiated

upward toward the roof the

chamber, incinerating,

along its way, an observation platform

overlooking the

doughnut-shaped magnet.

There were eight people

standing on the platform at

the time: a group of

sight-seers and their

guide. Deprived of their

platform,

the eight persons fell

to the

floor

of the

Bevatron chamber and

lay

in a state of injury

and

shock until

the

magnetic field had

been drained and the hard radiation partially neutralized.

Of the eight, four required

hospitalization. Two, less severely burned, remained for indefinite

observation. The

remaining

two were

examined, treated, and then

released.

Local

newspapers

in San

Francisco

and Oakland reported the

event.

Lawyers

for the victims drew up the beginnings of lawsuits. Several officials connected

with the

Bevatron

landed

on

the scrap heap, along with the

Wilcox-Jones Deflection System and its enthusiastic inventors.

Workmen appeared and began repairing the

physical

damage.

The incident

had taken only a few moments. At 4:00 the faulty deflection had begun, and at

4:02 eight people had plunged sixty feet through the fantastically charged

proton beam as it radiated from the circular internal chamber of the magnet.

The guide, a young Negro, fell first and was the first to strike the floor of

the chamber. The last to fall was a young technician from the nearby guided

missile plant. As the group had been led out onto the platform he had broken

away from his companions, turned back toward the hallway and fumbled in his

pocket for his cigarettes.

Probably

if he hadn’t leaped forward to grab for his wife, he wouldn’t have gone with

the rest. That was the last clear memory: dropping his cigarettes and groping

futilely to catch hold of Marsha’s fluttering, drifting coat sleeve… .

* * * * *

All

morning Hamilton sat in the missile research labs, doing nothing but sharpening

pencils and sweating worry. Around him his staff continued their work; the

corporation went on. At noon Marsha showed up, radiant and lovely, as sleekly

dressed as one of the tame ducks in Golden Gate Park. Momentarily, he was

roused from his brooding lethargy by the sweet-smelling and very expensive

little creature he had managed to snare, a possession even more appreciated

than his hi-fi rig and his collection of good whiskey.

“What’s

the matter?” Marsha asked, perching briefly on the end of his gray metal

desk, gloved fingers pressed together, slim legs restlessly twinkling.

“Let’s hurry and eat so we can get over there. This is the first day they

have that deflector working, that part you wanted to see. Had you forgotten?

Are you ready?”

“I’m

ready for the gas chamber,” Hamilton told her bluntly. “And it’s

about ready for me.”

Marsha’s

brown eyes grew large; her animation took

on

a

dramatic, serious tone. “What is it? More secret

stuff

you can’t talk about? Darling, you didn’t tell me

something important was happening today. At breakfast

you

were kidding and frisking around like a puppy.”

“I

didn’t

know at breakfast.” Examining his wrist watch, Hamilton got gloomily to

his feet. “Let’s make it

a

good meal;

it may be my last.” He added, “And this

may

be the last sightseeing trip I’ll ever take.”

But

he

didn’t reach the exit ramp of the California

Maintenance

Labs, let alone the restaurant down the

road

beyond the patrolled area of buildings and installations.

A uniformed messenger stopped him, a tab of

white

paper folded neatly and extended. “Mr. Hamilton,

this is for you. Colonel T. E. Edwards asked me to give

it

to you.”

Shakily,

Hamilton unraveled it. “Well,” he said mildly

to

his wife, “this is it. Go sit in the lounge. If I’m

not

out

in an hour or so, go on home and

open a can of pork

and

beans.”

“But—” She gestured helplessly. “You

sound so—so

dire.

Do you know what it

is?”

He

knew

what it was. Leaning forward,

he

kissed

her

briefly

on her red, moist, and rather

frightened

lips. Then,

striding rapidly down the corridor

after

the

messenger, he headed for Colonel

Edwards’ suite of offices,

the

high-level

conference rooms where

the

big

brass

of the

corporation were sitting in solemn session.

As he seated himself, the thick,

opaque presence of middle-aged businessmen billowed up around him: a compound

of cigar smoke, deodorant, and black shoe polish. A constant mutter drifted

around the long steel

conference table. At

one end sat old T. E. himself, forti

fied by a mighty heap of forms and

reports. To some

degree, each official had

his mound of protective papers,

opened briefcase, ashtray, glass of

tepid water. Across from Colonel Edwards sat the squat, uniformed figure of

Charley McFeyffe, captain of the security cops who prowled around the missile

plant, screening out Russian

agents.

“There you are,” Colonel

T. E. Edwards murmured, glancing sternly over his glasses at Hamilton. This

won’t take long, Jack. There’s just this one item on the conference agenda;

you won’t have to sit through anything

else.”

Hamilton

said nothing. Tautly, with a strained expres

sion,

he sat waiting.

This is about your wife,”

Edwards began, licking his fat thumb and leafing through a report. “Now, I

understand that since Sutherland resigned, you’ve been in full charge of our

research labs. Right?”

Hamilton nodded. On the table, his

hands had visibly faded to a stark, bloodless white. As if he were already

dead, he thought wryly. As if he were already hanging by the neck, squeezed out

from all life and sunshine. Hanging, like one of Hormel’s hams, in the dark

sanctity of the abattoir.

“Your wife,” Edwards

rumbled ponderously on, his

liver-spotted

wrists rising and falling as he flipped pages,

“has been classified

as a plant security risk. I have the report here.” He nodded toward the

silent captain of the plant police. “McFeyffe brought it to me. I should

add,

reluctantly.”

“Reluctantly as hell,”

McFeyffe put in, directly to Hamilton. His gray, hard eyes begged to apologize.

Stonily, Hamilton ignored him.

“You, of course,” Edwards

rambled on, “are familiar with the security setup here. We’re a private

concern, but our customer is the government. Nobody buys missiles but Uncle

Sam. So we have to watch ourselves. I’m bringing this to your attention so you

can handle it in your own way. Primarily, it’s your concern. It’s only

important to us in that you head our research labs. That makes it our

business.” He eyed Hamilton as if he had never set eyes on him before—in

spite of the fact that he had originally hired him in 1949, ten solid years

ago, when Hamilton was a young, bright, eager electronics engineer, just

bursting out of MIT.

“Does this mean,” Hamilton asked huskily, watching his two hands clench and unclench convulsively,

“that Marsha is barred from the plant?”

“No,” Edwards answered,

“it means

you

will be denied access to classified material until

the situation

alters.”

“But that means …” Hamilton heard his voice fade off into astonished silence. “That means all the

material I work with.”

Nobody answered. The roomful of

company officials sat fortified by their briefcases and mounds of forms. Off in

a corner, the air conditioner struggled tinnily.

“I’ll be goddammed,” Hamilton said suddenly, in a very loud, clear voice. A few forms rattled in surprise.

Edwards regarded him sideways, with curiosity. Charley McFeyffe lit a cigar and

nervously ran a heavy hand through his thinning hair. He looked, in his plain

brown uniform, like a pot-bellied highway patrolman.

“Give him the charges,”

McFeyffe said. “Give him a chance to fight back, T. E. He’s got

some

rights.”

For an interval Colonel Edwards

fought it out with the massed data of the security report. Then, his face

darkening with exasperation, he shoved the whole affair across the table to

McFeyffe. “Your department drew it up,” he muttered, washing his

hands

of

the matter. “You tell him.”

“You mean you’re going to read

it here?” Hamilton protested. “In front of thirty people? In

the

presence of every official of the company?”

“They’ve all seen the

report,” Edwards said, not unkindly. “It was drawn up a month or so

ago and it’s been

circulating

since then.

After all, my boy, you’re an important man here. We wouldn’t take up this

matter

lightly.”

“First,”

McFeyffe

said, obviously embarrassed, “we

have

this

business

from

the FBI. It

was forwarded to us.”

“You requested it?”

Hamilton inquired acidly.

“Or

did it just

happen to be circulating

back

and

forth

across

the

country?”

McFeyffe colored. “Well, we

sort of asked for it. As a routine inquiry. My God,

Jack,

there’s a file on

me—

there’s even a

file

on President Nixon.”

“You don’t have

to

read all that junk,” Hamilton said, his

voice shaking. “Marsha joined the Progressive Party

back in ‘48 when she was a freshman in college.

She con

tributed money to the Spanish Refugee

Appeals

Committee. She subscribed to

In Fact.

I’ve heard all that stuff

before.”

“Read the current

material,” Edwards instructed.

Picking his way carefully through

the report, McFeyffe found the current material. “Mrs. Hamilton left the

Progressive Party in 1950.

In

Fact

is

no

longer published.

In 1952 she attended

meetings

of

the

California

Arts, Sciences, and Professions, a

front

organization with

pro-Communist leanings. She signed the Stockholm

Peace

Proposal. She joined the Civil Liberties Union, described by some as

pro-left.”

“What,” Hamilton demanded,

“does

pro-left

mean?”