Fiction Writer's Workshop (2 page)

Read Fiction Writer's Workshop Online

Authors: Josip Novakovich

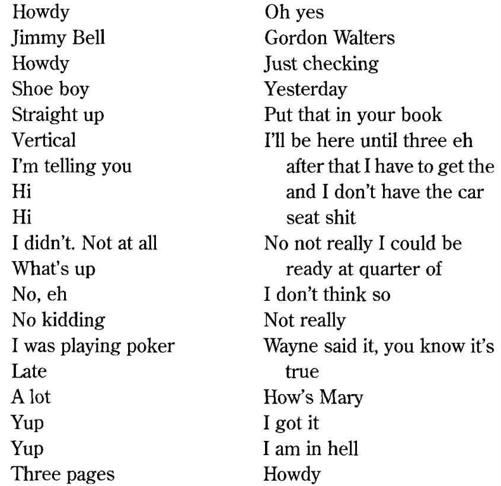

That was about fifteen minutes of talking, I think, to eight or ten different people. I believe most of this particular section occurred in the halls outside my office, with my co-workers or with my students. Whenever I ducked back inside my office, I scribbled in my spiral. Whenever I felt I was slipping into Cary Grant-speak, I just stopped talking, or found an excuse to go record in my spiral.

I was able to keep up with this from the time I woke until I went into my first class (about five hours), and I started again after my last class too.

What does it leave me with? Where's the connection to fiction? Well, I now realize that I jabber. I chatter on. I am, as I said, a wellspring of cliches and euphemisms. These are the very words and phrases I worry about most in my student's work and in my own. This sort of stuff has no place in fiction. In class, I say things like these: Avoid cliches. Don't let the dialogue rattle on. Compress. Don't lose the tension of a dialogue. And yet, when I talk, I sound like everything I am warning against. I sound, more disturbingly for me, like a prattling moron.

But sometimes jabber tells a story of its own. Return to my spiral notebook page. What can you draw out of it? Lots of greetings. Those took place in the halls of my office building, as I've already said, where I run into lots of students and fellow teachers. It's also because I teach at a small Midwestern college, where everyone seems to say hello no matter what mood they're in. These are matters of context, of setting. You also find very few complete sentences. Most of the exchanges are punchy, three or four words and no more. This too comes from context—the halls of a college between classes—but it also has to do with character. It's what I like to do. I float around, give people grief, then move on. Does everyone talk like this? Lord, no. But there was a time when I thought I spoke in full sentences. I've since found that, at one time or another, most of us don't. Finally, although I didn't punctuate the jabber, if you look closely at it, you'll see some rhythms, and in those you see my own tensions and stresses: I was worried about picking up my children; I was telling a student he had to give me three pages, no less; I was late, feeling overwhelmed. You see this in the incomplete sentences too.

Context, character, rhythm, tension and stresses. You'll be hearing a lot on these matters. I find them within a twenty-minute segment of my own life. You can too. It's worth studying the way you talk, the ways people around you talk. In these you can find the shapes of life. And by listening, you can begin the process of shaping dialogue to suit your fiction.

LISTENING: TUNING IN AND TUNING OUT

Listening is not easy. We train ourselves to tune out language. To get through a day during which you move from point A to point B in our culture, you have to slip in the word filter. Forget what

you

say for a moment. Button your lip. But think about all the words you hear. Deejays on the radio. Paging calls at the airport. The calls of a waitress to her short-order man. The voice at the drive-through. The two guys in the row behind you in the theater, the ones who just won't shut up. Not to mention the guy at work, the one who goes on about rebuilding an engine while you try to carve out ten silent minutes to eat your tuna salad on rye.

To live our lives without going bonkers, we run a sort of white noise over the top of all of this. We tune out, and we are trained to do so from the very start of our lives. We treat words the way we might treat junk mail or a forgotten toy. Words become scenery. The jabber of a cartoon on the television is a part of the background, even if it is in another room, part of the scenery in a home, the sort of voice we live with, the words no more than pulses, sounds without meaning.

Not me, you say. Maybe you live in the mountains, with your wolf, to whom you speak three words a day. Maybe you just boil the coffee in a tin pot and then chop wood for winter. At night you might lie down and say a blessing. Then you go to sleep without having said twenty words. No tuning out for you. No rush and razzle of contemporary life. Congrats! But I still think you should go buy a spiral. In fact, drive all the way into Butte, go to a mall and buy it at a chain drugstore. While you're at it, try

not

tuning a few words out. You'll be looking for the earplugs before you know it ("Aisle seven, on the right, next to the swimmer's ear drops. Right down there. Keep going. A little farther. There. Right in front of you. There. Look down. Yes. There. Okay.").

I have a sister-in-law, whom I like very much, who is hard of hearing. Every Christmas, I sit next to her on the couch during the festivities and find that she can hear me only when I shout directly into her ear. She won't wear her hearing aids. This past year, I asked her why. She told me that they work too well. "Hear too much," she said. "I hear everything—

everything

—when those are in my ears, every word that's spoken within forty yards. I hear people's stomachs. Everybody's shouting. And people talk so much. So many wasted words. Jabber. Jabber. Jabber."

It's a sad fact really that we are forced to filter out so much in contemporary life. We are assaulted by images from the moment we are born. No argument here. But we are in a hailstorm of words too. And to survive, we have to filter, tune out, stop listening. But to write

fiction, you have to listen. You have to tune in. Eavesdrop. Take note. But you also have to listen carefully. Select. Edit. Pare down. This is tuning out. These are opposite sorts of disciplines, but they are part of the same act. I guarantee it. Think of the world as if it were a short-band radio, which you can crank up when you need to. Indeed, you need to be able to turn up the power on your listening abilities to catch even the most stray signals on the most obscure channels. There are several ways to do that.

Jotting

First thing, start a journal. A spiral notebook like the one I used in the earlier exercise about listening will be fine, but it should be small enough to carry around with you. I have one I keep in the glove compartment of my truck. While I don't slip it into my pocket every time I leave the truck, I have taken it with me to meetings, malls and at least one county fair. Jot in it. Listen for good fragments. Try to catch oddball phrases.

How do you do this? You have to be comfortable eavesdropping for one thing. Sometimes you just get lucky. I play in a regular basketball game at noon, and the court is situated alongside two others in the middle of an indoor track. Before the game starts, I stretch my Achilles tendon like there's no tomorrow. I find this is quiet time for me, so I listen. A day or two ago, while the game was shaping up on the court, two or three groups of people were walking or running around the track. One couple caught my attention—two women, dressed in street clothes, walking. I could tell they worked in an office from the way they dressed and that they were fairly serious about the walking from the look of their shoes. Normally I would pass right by these two without a thought. Prime candidates for the word filter from the get-go. But as I stretched, I found they were easy to watch, cruising the far side of the track. One of the women, the heavier one, was doing most of the speaking, and the other one was listening. Soon they passed out of my line of vision and I started answering the hoots from the court—"Let's Go!" "Shake it out!" "Skin up!"—then as I passed from my stretching spot, I found that I was walking behind the women, as they had circled the track. And for a moment, I was close enough to hear one of them say, "That's what's funny about all of it."

Having seen even at a distance that it was a fairly animated story, I wanted to hear the rest, and as I was directly behind them, I took a step or two along the track, pretending to limber up some more. "When he took that day job," the woman said. Then no more. Someone from the court bounced me a ball. I caught it and walked behind, now fully tuned in. The woman went on. "Well, she was over there all morning just doing her business in that nasty little trailer."

The other woman howled. "Yucky!" she said.

At that point, I made a key mistake in my listening exercise: I casually bounced the basketball once. They became aware of my presence crowding them on the track. They fell silent and I slipped back, still disturbingly interested in that nasty little trailer, begrudgingly joining the game. Later, when I was in my truck, I took my spiral in hand and wrote down their exchange. I made a note about where I heard it, but not a long one.

Two women, circling: When he took that day job, she was over there doing her business in that nasty little trailer. Yucky.

This is jotting. I do it all the time. It's not exact recording. It's capturing a phrase or words and a circumstance. Nothing more. It's a fine starting point for writing dialogue. Just grab the words for whatever reason, and slap them down so they stay with you.

Why did I write these words? There's a story in them, of course. The nasty trailer, the marriage falling apart, the guy shifting jobs, the woman and her "business." That's good stuff, and I'm going to suggest throughout this book that good fiction can be created out of things overheard. But for me the news about the woman, the trailer, the "business" was not as interesting as the response it got from the other woman circling the track: "Yucky."

Why? Let's say you've never heard this exchange and you're writing a story. One character, Linda, is about to tell the other, say Helen, this juicy piece of gossip.

'When he took that day job," Linda said, pressing forward, "she started going over there to that nasty trailer every morning, doing her business."

Think like the writer now. What can Helen say? The news is out there. One choice would be to allow her response to invite the dialogue to slide forward, inviting another bit of news. This is so easy it's almost mindless.

"You're kidding," Helen said.

"No! Really?" Helen said.

"I can't believe it," Helen said.

"Wow," Helen said.

I'm a realist. Writing dialogue is tough, and sometimes you just have to let the characters say something that allows things to trip forward. After all, Linda will probably have more to say. But Helen's responses above are just jabber. If a writer uses one of these lines, or one like it, he's just using jabber to indicate the back and forth of a conversation. Back and forth, like a metronome. I would argue that this is not how most conversation runs, for one thing, but frankly I think this type of thoughtless response forces the reader to slip on the word filter.

What a waste that is. Think about it. You invite a reader into your story. The fact that you wrote it says you want the reader to pay attention to your words. So why let wasted words slip right into the mouths of your characters?

"Yucky" is a better response than any of those I suggested. The woman on the track could have said, "You're kidding," and I wouldn't have been surprised. Frankly I tuned in at that moment because the word "yucky" related so much of what she was thinking. It might have been the nasty trailer she was responding to or the woman's infidelity or her doing "her business" while her husband was at work. And while it's not a word I used a lot before (although now I do use it, having since test-piloted it into conversations, which, later on, I'll recommend to you), it is a word that might describe a reaction to all three of these bits of news. (In a trailer. Yucky! Infidelity. Yucky! Doing her business. Yucky!) Beyond that, it seemed like a word a kid would use, a word far too young for those two women circling my basketball game. And, notably, I think it was a funny response to what might be called bad news.

If I hadn't had my spiral in my glove box, I likely wouldn't have thought to write that down. But I'm in the habit because I make myself jot lots of things. A writer has many uses for a notebook, or a journal, uses that are well documented and well reasoned by writers far more accomplished than I. You should take notes vigorously. On everything. No argument here. But I'm telling you something a little more focused. I'm talking about jotting. Make a note on the physical circumstance, but keep it brief. No more than three words.

By the fountain:

What's the flower? What's the symbol?

Running:

No. No. No. I'm. I'm. I'm not.

On a plane:

That's why it always goes this way.

So true.

And weddings are usually a disaster because of it.

New York:

I take photographs. But I'm not a photographer.