Fighter's Mind, A (23 page)

Authors: Sam Sheridan

Frank maintained that this process has helped him check his ego. He knew he had a reputation for being an occasional egomaniac. “If my ego was so big, I would never need to visualize anything. I would just do it and everything would be a hundred percent wonderful, right?”

I thought of Eddie Bravo’s discussion on ego, and Frank had a lot to say about it. “Ego is an evil thing. Confidence is important, but ego is something false. Humility is the way to build confidence, and ego is hugely dangerous in this sport, because if you’re running on ego you aren’t running on good clean emotions, or cause and effect. You bypass it to support a false idea. It’s all garbage, the ego is garbage.

“The hardest thing about being an MMA fighter is the huge ego boost you get from winning—not only from yourself but from your community. I hear, ‘Oh you’re the greatest, you don’t have to train all the time.’ Marcelo Garcia made the exact same complaint.

“Your own community is the hardest on you, because they’re in love with ego, too, and you have to fight yourself

and

them now. Anyone can fight, fighting is easy, but to sustain it, to remain normal and relaxed and grounded within yourself and your community, is really challenging.”

and

them now. Anyone can fight, fighting is easy, but to sustain it, to remain normal and relaxed and grounded within yourself and your community, is really challenging.”

This is related to the other aspect of fighting that Frank has found to be challenging: fame. “Being famous is hard to do—it amplifies everything negative and positive about you. It’s amplified by your fans, whoever watches you. I see guys get famous and that’s a big test for them: what will you do with your ego and power and influence now?

“False ideas about yourself can destroy you,” Frank said. “For me, I always stay a student. That’s what martial arts are about, and you have to use that humility as a tool. You put yourself beneath someone you trust. That’s extremely useful.

“There is a belief in our system”—he was referring to his school—“that I came up with years ago, that it takes three people to make you into the best person you can be. Somebody better than you, someone equal to you, and someone less than you. People hear that and get freaked out, because they want to be better than everyone, or at least equal. The goal is actually to put yourself as the last person, even if you’re the guy in the lead. You can

always

find something other people are better at. So teach me, show me, let’s work on that. If you can accept the humility and understand why it’s important, you’ll grow so strong in every way. Imagine if you did that to every person you came in contact with? You put yourself underneath them to learn? I always stay a student.”

always

find something other people are better at. So teach me, show me, let’s work on that. If you can accept the humility and understand why it’s important, you’ll grow so strong in every way. Imagine if you did that to every person you came in contact with? You put yourself underneath them to learn? I always stay a student.”

Frank launched into one of his favorite topics, his own scientific approach. “I study the biomechanics of the human body and look for the angles of strength. Where energy is distributed—I break down techniques into how much energy they expend. I go through the technique in my mind, and if your mind sees it, it happened. Whether it’s true or not, if your mind saw it, it happened. So I go through these techniques mentally. My confidence gets built up and I go in and try them, and then I evaluate it, think about how it worked. There’s always something that could be better, so you stay a student.”

One of the things I was interested in was the pysch-out games Frank played. He would very famously talk shit. He made it very clear that, at this level, anything was fair game.

“I listen to people,” he said. “They will inherently tell the truth about themselves—it always happens. I amplify things they say about themselves, either right or wrong. But the truth is stronger than anything. If you know a guy has bad feet, then he’s got bad feet! Just tell the truth. Some people, when they hear something like that, will fight it. They’ll argue, ‘Oh, no, it’s not like that.’ Now the game is on—because you’ve got a guy defending something you both know is false. He

should

say, ‘You’re so right, and I’m grinding in the gym to make myself better,’ but ego jumps in, ‘Of course I’m good and my footwork is fantastic!’” He gives me his now-familiar smile. “If someone says to me, you’re hands suck then I’ll be in the gym working on that extra hard for the next six months.

should

say, ‘You’re so right, and I’m grinding in the gym to make myself better,’ but ego jumps in, ‘Of course I’m good and my footwork is fantastic!’” He gives me his now-familiar smile. “If someone says to me, you’re hands suck then I’ll be in the gym working on that extra hard for the next six months.

“Everyone has stuff they get nervous about, their personal shit, and if you hang around long enough they’ll volunteer it, or they’ll tell somebody else for you. I go after that stuff. Phil Baroni stutters. We know it, he knows it. Most people don’t pick up on it. But Phil hasn’t made peace with it. When I’d goof on him, he’d get mad.”

In one press conference, Phil was almost in tears. I get what Frank is about. He’s not picking on Phil out of nowhere, he’s not just an asshole. Mental toughness is on the table.

“Now he’s not in a peaceful mind, ready to fight. Now he’s somewhere else, some other issue from when he was a kid. He’s not focused on the task or the goal.

“I talk to people during fights the whole time. I build on what I said beforehand. I picked that up from Bas Rutten. We’d both talk to each other the whole fight, and the ref used to warn us. Bas was funny. He’d talk to me as a way to pump himself up, ‘I’m so strong, I almost got you,’ more like Muhammad Ali, to empower himself. What he did wasn’t crafted to get into you, but I’m all about that privacy, that inner attack. It’s distracting and confusing and it’s supposed to be. If you hear it, it exists. Especially if you’re in a high-stress situation, with uncertainty anyway. I look in a guy’s eyes, and I talk down low, just for him. I don’t want anyone to hear it but him, not his corner, not the crowd. So when he goes back to his corner, and his trainer is telling him things, there’s another voice he’s been hearing. It falls into what he thinks about.”

This may be why some MMA fans dislike Frank; shenanigans like this are frowned on in martial arts. But Frank assured me that mental strength and focus are fair targets at this level of fighting. “It’s part of the game,” he kept saying.

Frank even confessed to a time when he was head-fucked by another fighter. It was the second time he fought John Lober, and Lober engaged in psychological warfare of a petty nature—ordering room service to Frank’s room, sending him threatening e-mails, prank calling him, getting personal.

“It was weird, funny childish stuff, but it made me upset. I was young, I had to learn. I went out all angry and kicked the shit out of him, but when it was over I had a big sobering up. I realized

holy shit I exposed myself,

being angry and frustrated. There was a moment when I could have finished him, and I thought no, I wanted to hurt him, and that could have been really bad. I could have let him off the hook, and he might have come back. I could have hurt myself or gotten hurt. He got in my head, plain and simple.”

holy shit I exposed myself,

being angry and frustrated. There was a moment when I could have finished him, and I thought no, I wanted to hurt him, and that could have been really bad. I could have let him off the hook, and he might have come back. I could have hurt myself or gotten hurt. He got in my head, plain and simple.”

I was reminded of Dan Gable talking about seeing a guy break, and staying on him—because if you gave him respite he could come back. Frank agrees wholeheartedly. “You have to stay on him when you see him start to break. My style is to break you. I try to get you to go anaerobic—change your fuel source so you’re no longer efficient, or you’re afraid of running out of gas, of getting knocked out. I fight at a pace that borderlines aerobic activity, which is hard to do unless you’ve got good technique. Don’t worry so much about positions, but keep the fight flowing at a fast pace. It’s a race. The person with the best conditioning and technique should win. I didn’t hurt Tito, I made him tired.”

Frank was talking about his epic battle with Tito Ortiz, one of the great early MMA fights. Frank fought the larger, younger, and angrier Tito for four long rounds, and in a superb technical display he finally started to take Tito apart in the fourth.

“Tito tapped because he was exhausted, and I was going to keep beating him. When you’re dog tired that lactic acid builds up, and you get sick and nauseous, and you have to do something. You can’t keep fighting. It’s conditioning. If you push them over the brink, they’ll lose everything. They break down, they feel like they could die. Fatigue makes cowards of us all, right?

“Anytime you can take a technique from somebody—absorb a big blow without damage, stuff a takedown—that’s huge. I don’t consciously do it, I technically do it. I train for it. If he’s got a great uppercut, I shift my hand over and take that away from him. I don’t think about it, but I can feel his energy subside when he thinks he’s done something good and it doesn’t work. You can feel him deflate. I’m always in tune with his energy, his emotions. You fight in front of thousands, but there’s only one guy. I hear him breathing, I hear the impacts, and I hear my corner, that’s it.”

Frank found spirituality in what he does, in teaching and training. “The core of every religion is a social structure that connects everybody, for the common good of society,” he said in a rehearsed line that rolls off his tongue. “For me, that’s what martial arts is. You teach children to make them better people, you teach adults to give them a better understanding of themselves, or of their partner. Some students will ask me to go to church with them on Sunday, and I say, ‘I go to church Monday through Saturday and Sunday I stay home with my family.’ That’s how I look at it.”

EVERYTHING IS ALWAYS ON THE LINE

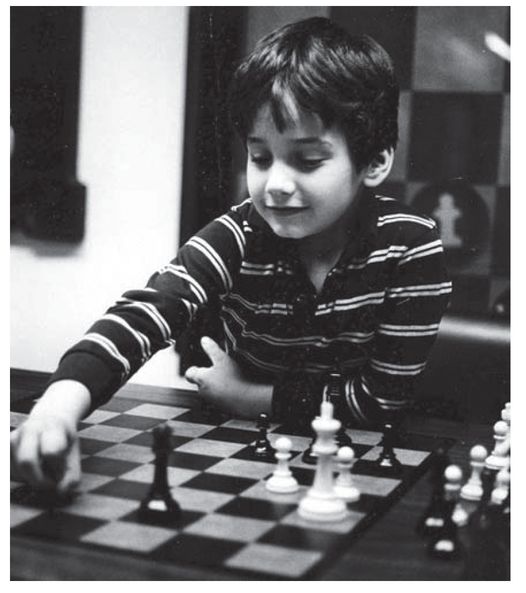

Josh Waitzkin playing chess as a kid.

(Courtesy: Josh Waitzkin)

(Courtesy: Josh Waitzkin)

Josh rolling with Marcelo Garcia in preparation

for Abu Dhabi.” (Courtesy: Marcelo Garcia)

for Abu Dhabi.” (Courtesy: Marcelo Garcia)

I first became aware of Josh Waitzkin through a friend from New York who’d played chess with him when they were both kids. “Did you ever see that movie

Searching for Bobby Fischer

? I drew that kid in a game,” he said, over a chessboard. “We were nine.” Not only had I not seen the movie, I hadn’t been aware that nine-year-olds played in chess tournaments. When I was nine I focused on tying my shoes and killing salamanders.

Searching for Bobby Fischer

? I drew that kid in a game,” he said, over a chessboard. “We were nine.” Not only had I not seen the movie, I hadn’t been aware that nine-year-olds played in chess tournaments. When I was nine I focused on tying my shoes and killing salamanders.

When I left Thailand, sailing across the Indian Ocean, I started reading chess books, just because I hadn’t studied anything since college. Funnily enough, one of the books I ended up with was Josh Waitzkin’s

Attacking Chess,

written when he was eighteen. I enjoyed the story more than the chess, which is a common thread for me; I buy chess books and read the introductions.

Attacking Chess,

written when he was eighteen. I enjoyed the story more than the chess, which is a common thread for me; I buy chess books and read the introductions.

Later, when I was living briefly in Manhattan and studying tai chi with William C. C. Chen, I saw pictures on the wall of that same chess kid, Waitzkin, winning “push-hands” tournaments. Push-hands is the competition side of tai chi, a kind of flowing, standing wrestling where you push and pull, trying to either push an opponent out of the ring or “fall” him. It’s pretty fringe in the United States but a major deal in China and Taiwan, and Josh had gone there and won world championships. Now, push-hands is not MMA, but it’s also not a joke, especially overseas, where it’s taken as seriously as judo.

I finally watched

Searching for Bobby Fischer,

based on a book that Josh’s “Pop” had written about Josh’s early chess career. It’s a great story about a chess prodigy coming to terms with competition and life, and a fascinating look into the cutthroat world of child chess in New York, high-stakes pressure tournaments for eight-year-olds.

Searching for Bobby Fischer,

based on a book that Josh’s “Pop” had written about Josh’s early chess career. It’s a great story about a chess prodigy coming to terms with competition and life, and a fascinating look into the cutthroat world of child chess in New York, high-stakes pressure tournaments for eight-year-olds.

At the age of six Josh had been walking by Washington Square in Manhattan and was lured in by the commotion of “street” chess. The Square has a famous corner where hustlers play for money, raucous as any street basketball court. I’ve played there, and it’s a little rough on the ego to get shit-talked to, then slapped around the board by a black guy with muscled arms bigger than your legs. Josh started playing with these boisterous characters without ever seeing a chess board before, and he started coming back every day, winning more than he lost. With this rough apprenticeship, he’d gone on to become one of the top young players in the country. His story is powerful, and made more so by his struggle to maintain his identity and hold on to his childhood in a chessic world without mercy.

I had picked up a new book Josh had recently written, a nonchess book called

The Art of Learning

. The back is covered with intimidating quotes, effusive praise by everyone from Cal Ripken Jr. to Deepak Chopra—you better like it. Fortunately, it’s easy to like. It’s a great book, an honest and open look into Josh’s thought processes, and the lessons he’d gleaned from his study of the world. The book takes into account both his chess and tai chi careers, and I would recommend it to anyone. Josh has been in deep waters, at least in chess and tai chi, and he’s drawn genuine insight from them. At the end of the book he mentioned he was studying Brazilian jiu-jitsu, and that drew my attention. I knew some people who knew him, so I managed to get in touch. We set up a time to meet in New York.

The Art of Learning

. The back is covered with intimidating quotes, effusive praise by everyone from Cal Ripken Jr. to Deepak Chopra—you better like it. Fortunately, it’s easy to like. It’s a great book, an honest and open look into Josh’s thought processes, and the lessons he’d gleaned from his study of the world. The book takes into account both his chess and tai chi careers, and I would recommend it to anyone. Josh has been in deep waters, at least in chess and tai chi, and he’s drawn genuine insight from them. At the end of the book he mentioned he was studying Brazilian jiu-jitsu, and that drew my attention. I knew some people who knew him, so I managed to get in touch. We set up a time to meet in New York.

Josh had been a star from six years old, immediately labeled “special” in the eyes of adults, and different than most kids . . . but then a hit movie about how wonderful you are, when you’re fifteen? What could that do to your ego? To be honest, I was pretty sure he was going to be an asshole. It was almost impossible for him NOT to be.

He was taking jiu-jitsu, though—with an eye on competing in the Mundials (the world championship). I thought,

Perfect, here’s a guy I can talk chess and jiu-jitsu with

. If he was an asshole I could handle it.

Perfect, here’s a guy I can talk chess and jiu-jitsu with

. If he was an asshole I could handle it.

Other books

The Fortune Cafe by Julie Wright, Melanie Jacobson, Heather B. Moore

Locked by Maya Cross

Sentido y Sensibilidad by Jane Austen

Mouse Noses on Toast by King, Daren

Race Against Time by Christy Barritt

Slave Jade by Claire Thompson

Thief of Light by Rossetti, Denise

The Avenger 7 - Stockholders in Death by Kenneth Robeson

Might as Well Be Dead by Nero Wolfe

The Killing Hour by Lisa Gardner