Finding Arthur (2 page)

Authors: Adam Ardrey

Tags: #HIS000000; HIS015000; BIO014000; BIO000000; BIO006000

Glossary of Names

T

HE

S

COTS

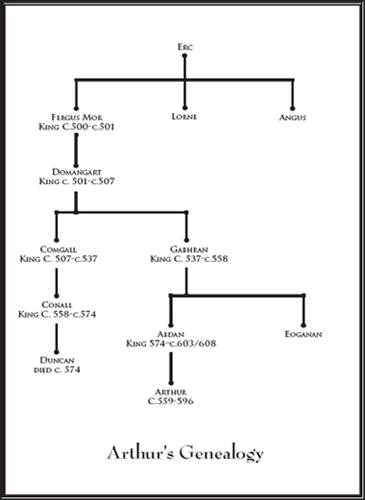

Fergus Mor Mac Erc, Fergus the Great, Arthur’s great-great-grandfather, the man who led a Scots army from Ireland to Scotland c. 500 (r. 500–501)

Domangart Mac Fergus, Arthur’s great-grandfather (r. 501–507)

Comgall Mac Domangart, Arthur’s granduncle, king of the Scots (r. 507–538)

Gabhran Mac Domangart, Arthur’s grandfather, (r. 538–559)

Conall Mac Comgall, king of the Scots (r. 559–574 ), Arthur’s second cousin once removed

Aedan Mac Gabhran, Arthur’s father, king of the Scots (r. 574–608)

Arthur Mac Aedan

Éoganán, Arthur’s uncle

Duncan, Arthur’s third cousin

S

TRATHCLYDE

Rhydderch, king of the Strathclyde Britons (r. 580–612)

Gwyneth, daughter of Morken of Cadzow, twin-sister of Merlin-Lailoken, wife of Rhydderch, queen of Strathclyde, known as Languoreth (the Golden One), The Swan-Necked Woman, The Lioness of Damnonia

Merlin-Lailoken, son of Morken of Cadzow, twin brother of Languoreth, Rhydderch’s chief counselor, a leading druid

Gawain, Arthur’s nephew by the first marriage of his sister Anna

Cai (Kay), one of Arthur’s warriors, perhaps his foster-brother

Gildas,

Gille Deas

, Servant of God, son of Caw of Cambuslang

Hueil, Gildas’s brother

Domelch, a Pictish princess of Manau, possibly Arthur’s mother

Ygerna/Igraine, a lady of Strathclyde, possibly Arthur’s mother

T

HE

P

ICTS

Bridei Mac Maelchon (Brude Mac Maelcon), king of the Miathi Picts

Guinevere, a princess of the Picts of Manau, Arthur’s wife

T

HE

A

NGLES

Hussa, king of the Angles of Bernicia (r. 585–593)

Hering son of Hussa, an Angle prince

Aethelfrith, king of the Angles of Bernicia (r. 593–616)

T

HE

G

ODODDIN

Mungo, son of Taneu (a princess of the Gododdin) and a lord of Strathclyde

Mordred, son of Arthur’s sister, Anna, by her second marriage to Lot of the Lothians

“There is … no more difficult task than to substitute the correct ‘

sumpsimus

’ for the long cherished and accepted ‘

mumpsimus

’ of popular historians. All that the Author has attempted … is to show what the most reliable authorities do really tell us of the early annals of the country [Scotland], divested of the spurious matter of superstitious authors, the fictitious narratives of our early historians, and the rash assumptions of later writers which have been imported into it.”

—W. F. S

KENE

,

Historiographer Royal to Queen Victoria

Introduction

F

OR MORE THAN A THOUSAND YEARS INNUMERABLE WRITERS HAVE

invented stories about King Arthur. Even now, children all over the world grow up hearing tales of Arthur’s legendary adventures with the Knights of the Round Table, his love for Guinevere, his friendship with the magician Merlin, and his mythical home in Camelot.

The writers telling these stories have been, by and large, Christian, English, and monarchist. Naturally, their Arthur has been portrayed, almost invariably, as a Christian English king—perhaps the greatest one of all.

But was he any of these things? Who was the historical Arthur, really? When did he live? Where did he live? What did he do? Why did he do it? Why is he so famous?

The question

Who was Arthur?

has confounded scholars for centuries. It has never been satisfactorily answered or, at least, it has never been answered in a way that allows all these other questions to be answered too.

Geoffrey of Monmouth’s twelfth-century

History of the Kings of Britain

is one of the main pillars upon which the story of Arthur stands. According to Geoffrey, his

History

was based on “a certain very ancient book written in the British language,” which was given to him by his mentor, Walter, Archdeacon of Oxford. Unfortunately Geoffrey did not identify this book, and it is now lost.

Some fifty years after Geoffrey wrote his

History

, a bishop of Glasgow

commissioned a monk called Jocelyn of Furness to write a hagiography of a local saint, Mungo Kentigern (now patron saint of Glasgow). Jocelyn’s

Life of Kentigern

contains much of what we currently know about the story of Merlin. According to Jocelyn, his book was based on a “codicil, composed in the

Scottic

style” that he found while going about the streets and quarters of Glasgow. Like Geoffrey of Monmouth, Jocelyn did not identify his source material, and it too is now lost.

Some 820 years after Jocelyn wrote his

Life of Kentigern

, I wrote in my previous book,

Finding Merlin

, of an “eighteenth-century book based on sixth- to ninth-century sources,” in which I found evidence that enabled me to identify the historical Arthur. Like Geoffrey and Jocelyn, I chose not to name my source, as I thought it was more a part of Arthur’s story than of Merlin’s. Some readers were justifiably annoyed when I said I would identify this book but that this would “have to wait until later.” Fortunately, unlike Geoffrey and Jocelyn, I am now able—and willing—to name my source: John O’Brien’s

Focalóir Gaoidhilge-Sax-Bhéarla; An Irish-English Dictionary

, which clarified the connection between the earliest reference to Merlin, at the Battle of Arderydd in the year 573, and the presence of a historical Arthur at a place called Dunardry in 574.

Until I found that “eighteenth-century book based on sixth- to ninth-century sources,” I had had no particular interest in Arthur or in Merlin. I liked television programs and films about the “Knights of the Round Table” when I was a boy, but I also liked Sword-and-Sandal epics and Westerns. The comics and the books I read as a child were as likely to be about Custer and his Seventh Cavalry, or Jason and his Argonauts, as Arthur and his Knights. I was an equal-opportunity hero-worshipper.

The Arthur who appeared in these children’s stories was almost always the same character. The young Arthur was the pure and simple boy of the Disney cartoon

The Sword in the Stone

, a film inspired by T. H. White’s book

The Once and Future King

. The adult Arthur could also be found in film—the musical

Camelot

; John Boorman’s atmospheric

Excalibur

; the stolid

Knights of the Round Table

starring Robert Taylor—as well as in television shows such as

The Adventures of Sir Lancelot

. This Arthur was almost always an avuncular stay-at-home,

who lost the woman he loved to his best friend, the dashing Lancelot. Worse still in the boyhood-hero-stakes, this Arthur lacked the warrior spirit and fighting prowess of his rival.

Like most people, I pictured King Arthur’s Camelot as existing in some vague conception of the Middle Ages inspired by Thomas Malory’s

Le Morte d’Arthur

: a place of turreted castles somewhere in England, inhabited by men in plate armor and women in pointed hats topped with chiffon. It was only later that I realized there was no historical Arthur in medieval English history, far less a “King” Arthur, and came to accept the general consensus that if there really was a historical Arthur he must have lived in the late fifth or early sixth centuries. Later still I found out that there was no historical Arthur in the late fifth or early sixth centuries either.

If I had known when I was a boy that Geoffrey’s “ancient book” was in a “British language”—that is, in a Celtic language—and that Jocelyn’s codicil was “Scottic,” I might have guessed that Arthur was probably a Celt and possibly a Scot and looked to the north to find him. But along with almost everyone else I did not doubt the conventional wisdom that Arthur had lived in the south of Britain.

It was only in 1989, when I read Richard Barber’s

The Figure of Arthur

, that I realized there was another possible Arthur, a Scottish one. However, after considering a goodly number of possible Arthurs, Richard Barber concluded that “Short of some fantastic invention, a time machine, say, or an equally fantastic discovery, an inscription naming him from a period which has barely left a word engraved on stone, Arthur himself will always elude us.”

1

I thought Barber was right and accepted that Arthur would always elude us, unless, of course, someone discovered something fantastic. I didn’t imagine that I’d be the one to make or even to pursue such a discovery. Why would I? People who set out on such quests—and they do usually refer to them as quests—often end up as eccentrics, at best. Then, by sheer chance, I came across the source I’ve already mentioned, and the real story became clearer than I ever thought possible.

Several years ago, I was researching my family name in advance of a trip I’d planned with my young son to Argyll, Scotland, where our family had lived before they became part of the Protestant Plantation

of Ireland in the seventeenth century. As I researched, two things helped me to look where no one else had looked and find what no one else had found: first, that our name, Ardrey, is rare in the extreme, and second, that very few people are interested in family trees other than their own. In a great many ways, I was lucky.

When I was at school in Scotland, “British” history—in effect English history—was promoted and Scottish history was played down. Despite or perhaps because of this cultural indoctrination, I came to number among my heroes Scots who had been all but airbrushed out of history: men like William Wallace (of the film

Braveheart

) and Robert the Bruce, the real braveheart of history. This one-sided schooling left me open to the possibility that the story of Arthur too could have been worked on and warped for political purposes.

Anyone who, like me, believes in democracy not monarchy and in people not the supernatural will find it easier to picture a pre-Christian Arthurian Britain than someone like Queen Victoria’s Historiographer Royal for Scotland, W. F. Skene, would have. A man in thrall to organized religion, Skene had a Christian Monarchist blinker on one eye and a British Monarchist blinker on the other. Even so, there are places in his work where it seems he might have known the truth but been too cautious to say it, lest he lose his prospects of further preferment. Even the great Charles Darwin waited twenty years before publishing his ideas about evolution because he was wary of the Church’s potential reaction.

If the search for Arthur in the south of Britain was ever in a period of upward momentum, it would now be possible to say that it has ground to a halt. Some southern-leaning historians claim there was no historical Arthur, others that there was no single historical Arthur but lots of proto-Arthurs. At best they are reduced to relying upon some soul’s slight echo in history to found their claims.

The dearth of substantial evidence in the South has not led to a vigorous search for evidence in the North. In the North, fear of being labeled parochial shrivels “scholarly” inquiry. Fortunately, now that evidence is more widely available, popular culture has started to place Arthur in Scotland, in films like the otherwise risible

King Arthur

in 2004. But despite the fact that many of them are as clever as screenwriters,

professional historians do not appear to be as open to new ideas or, indeed, evidence.

Living in Scotland I was well-placed to find evidence, literally, on the ground. Indeed I had so much evidence while writing

Finding Merlin

that I neglected to say that the purportedly magical spring of Barenton, where Merlin is supposed to have met a woman called Vivienne and which is said to be in the forest of Brocéliande in France, is really in Barnton, Edinburgh. The spring is still there, for all to see.