Finding Arthur (31 page)

Authors: Adam Ardrey

Tags: #HIS000000; HIS015000; BIO014000; BIO000000; BIO006000

The sixth battle on the battle-list of Nennius was fought “on the river called Bassas.” Three clues: Bassas is the sixth battle; Bassas was fought on a river; and the name, Bassas.

The historical circumstances surrounding the sites of the first five battles strongly suggested that the battles on Nennius’s list were in chronological order. Glein, Arthur Mac Aedan’s first battle (or rather campaign) had been fought to secure his father’s throne in the Glens

of Argyll. Battles two to five, the Douglas battles, in reality four campaigns, had been fought by Arthur on the eastern marches of Dalriada, to secure the borders of his father’s new kingdom in the face of Pictish incursions. Bassas was the sixth battle.

Having fought the Picts to a standstill in the Douglas campaigns, Arthur had no reason to fall back and little reason to stay where he was and wait to fight on the defensive again. In similar circumstances great generals such as Alexander, Caesar, Napoleon, and Lee would have advanced, and so, if as seems likely Arthur too was a great general, Arthur too would have advanced. This meant there was a good chance that the site of Arthur’s next battle, the Battle of Bassas, would be in enemy territory, in the land of the Picts.

The second clue, the river reference, is a blunt thing. While battles were frequently fought at river crossings there are too many rivers in too many places to allow any meaningful search to be based upon this second clue alone. When I came to this point I found I needed more to go on, and so I left this second clue to stand, to be used as a cross-check if I could find something to cross-check it against.

Clue three, the name Bassas, had been done to death—this was, after all, the battle that had caused scholars to despair. According to the Arthurian scholar, August Hunt, “The Bassas river is the most problematic of the Arthurian battle sites, as no such stream name survives and we have no record other than this single instance in the

Historia Brittonum

of there ever having been a river so named.”

5

Like everyone else who had tried to solve the Bassas problem, I considered the prefix

bas

or

bass

, because, like everyone else, I could not find a British place-name that contained the whole word

Bassas

. Everywhere I looked someone had been there before me; every place and name I considered was a dead end.

Like everyone else who had looked for Bassas before me I found the search long and difficult, right up to the point when everything clicked into place and I knew exactly where the Battle of Bassas had been fought and how to prove it. Then I found other

entirely separate evidence

and proved it for a second time.

The Romans divided the lands of the Miathi Picts when they built the Antonine Wall from the rivers Clyde to the Forth around the year

142 CE. The Miathi Picts who found themselves south of the wall came increasingly to accept what the Romans could do for them: roads, public health, civil security, the rule of law, that kind of thing. North of the wall the Miathi Picts were presented with a stark choice: accept this dilution of their power in the south or rise against Rome. In 207 CE they rose against Rome and forced the Roman Emperor, Septimius Severus, to come north with his legions to protect his frontier.

Severus was the model for Maximus, Russell Crowe’s character in the film

Gladiator

, although, unlike Maximus, Severus did not die in the arena. Severus became emperor after the death of the vile Commodus, played by Joaquin Phoenix in the film. Commodus did not die in the arena either, as he did in the film; he was strangled in his bath in December 192.

Severus was an outsider, a self-made man from the provinces and, in the words used in the film, a soldier of Rome. He ruled the empire harshly but well until his death in 211. He married twice and had two sons, one to each wife. When his oldest son was seven years old Severus re-named him Marcus Aurelius Antoninus to lend legitimacy to his line by associating his family with the much loved philosopher-emperor, Marcus Aurelius (played by Richard Harris in the film). As so often happens with the sons of famous, successful, powerful, self-made men, Antoninus and his younger brother, Publius Septimius Antoninus Geta, were not as able as their father; on the contrary, they were ambitious, effete, dissolute, and vicious: “The fond hopes of the father, and of the Roman world, were soon disappointed by these vain youths, who displayed the indolent security of hereditary princes; and a presumption that fortune would supply the place of merit and application.”

6

Gibbon said Severus brought Antoninus and Geta with him to Britain to keep them away from the fleshpots of Rome, but it is more likely that Severus knew he did not have long to live and that if he left Antoninus and Geta behind in Rome they would cause trouble by plotting against each other to succeed him. Antoninus, who was to succeed his father as emperor, was a monster to equal the emperor Gaius, a man better known by the sobriquet Caligula (said to mean “Little Boot”). Antoninus had a nickname too, one that has gone down in history as a byword for savage excess, Caracalla.

Close to the end of his reign, sick and near to death, Severus had

himself carried north in a litter to fight the Miathi Picts. His elder son Antoninus-Caracalla was given a military command and came with him. His younger son Geta was left to work at staff-headquarters in York. The Romans “passed … fortresses and rivers and entered Caledonia,” clearing woods, laying roads, and building bridges as they went. They built a road from Falkirk to Stirling, which they extended west along the banks of the Forth before turning north and building a massive fortified camp where the River Earn joins the River Tay at a place that is now called Carpow. There, at this camp, the Roman army could be supplied from the sea.

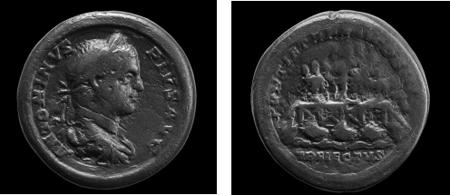

The Romans built two bridges at Carpow. A coin of Severus, dated to the year 208, shows a fixed bridge, and a medallion, dated to Antoninus-Caracalla’s twelfth Tribunical year, 209, shows a bridge of boats. It makes sense to suppose that the bridge of boats spanned the wide Tay (the remains of the bridgehead works have been found on the north bank) and that the fixed bridge was across the narrow Earn, west of Carpow fort. Antoninus-Caracalla’s name continued to be connected with this area even after he left Scotland to become emperor. A tile found at Carpow dedicated to Caracalla has been dated between 212 and 217. This suggests some continuing building work at Carpow and a continuing connection with, or at least a memory of, Antoninus-Caracalla.

Coin from 209 CE showing the bridge at the site of the Battle of Bassas. “Antoninus” was an official name of the man earlier named Bassianus, although better known as Caracalla. On the reverse, Pontif refers to the office of Pontifex Maximus; “TR-P XII” refers to Bassianus’s twelfth tribunate; and “COS III” to his third consulship. “Traiectus” means a crossing

.

©

The Trustees of the British Museum

When Julius Caesar bridged the Rhine the people who lived on its banks thought their river had been captured: “

Rhenum suum sicponte quasi iugo captum

.”

7

Even if the people who lived on Tayside and Earnside were not quite so simple, they must have been impressed by the extraordinary engineering of the Romans. Given that these bridges were built under the command of Antoninus-Caracalla and that he became Roman emperor soon after they were completed, it would be reasonable to suppose his name was associated with these bridges.

The bridge of boats may not have withstood the pressure of the River Tay for long, but the fixed-bridge over the River Earn could have survived for generations. It is possible that this bridge was remembered as the bridge Antoninus-Caracalla built and that consequently his name became a place-name that survived the bridge itself.

The Miathi Picts, knowing they were no match for the Romans in the open field, offered peace, but Severus rejected their overtures. He needed a quick and decisive victory. The Picts had time. Severus did not. Severus was dying. The Miathi Picts fell back before the Roman advance and waged guerrilla war. Severus, finding himself unable to bring them to battle, took out his frustration on the civilian population. He cruelly crushed all who opposed him, and many who did not, and so despoiled the lands of the Miathi Picts that they were forced to come to terms.

Antoninus-Caracalla, quite naturally for a young man of wild disposition, resented his father for bringing him to what must have seemed to him a dank and dreary place compared to Rome and, in time-honored fashion, expressed his resentment by being as contrary as he could. Severus wanted merciless action and a quick resolution of the campaign, and so Antoninus-Caracalla took an opposite tack and became relatively sympathetic towards the Picts. Unlike Severus, Antoninus-Caracalla was no soldier; he had no interest in expending energy crushing Picts on the furthest borders of the empire. All he wanted was that his father should die and that he should be emperor of Rome. He even went as far as to plot with the Picts to have Severus assassinated while peace negotiations were ongoing.

The treatment meted out by Severus to the Miathi Picts was so severe that their neighbors, the Caledonian Picts, afraid they would be

next to suffer at the hands of Severus, offered the Miathi Picts their support. With the Caledonian Picts to back them up, the Miathi Picts broke the peace they had only just made and attacked the Romans. Severus, unable to join the army in the north because of ill-health, gave orders that his army show no mercy and that resistance be met with massacre: everyone was to die, men, women, and children.

Antoninus-Caracalla, who was at least nominally in command in the north, did not follow his father’s policy. His inaction was not motivated by sentiment but by self-interest: Antoninus-Caracalla was, after all, a savage. He knew that Severus would soon be dead and that if he were to become emperor in his father’s place he could not be away from Rome fighting Picts in the northern fastnesses of Britain when the succession was decided. If Severus died it would have been difficult for Antoninus-Caracalla to leave the scene of battle and return to Rome with rebellious Picts still rampant on the borders of the empire, and so it was in his interest to create conditions that would allow him to leave a peaceful Scotland behind him. To achieve this end Antoninus-Caracalla did not just damn his father’s orders with faint obedience, he completely ignored them; indeed, he contradicted them. Severus was for utmost war and so Antoninus-Caracalla became a craven appeaser. He did not burn villages, kill their inhabitants, and “take-no-prisoners,” as his father had ordered. He made contact with the leaders of the Picts, spared their families, and negotiated a truce. At the same time he put out feelers to discover on what terms he might make peace and so facilitate the façade of an honorable withdrawal.

The Caledonians and the Miathi Picts were still in revolt when Severus died in 211, leaving Antoninus-Caracalla, who had made himself their friend, free to make peace with the Picts as he had planned. He simply received pledges of fidelity and left Scotland to become Emperor.

8

Initially Antoninus-Caracalla became joint-emperor with his brother Geta, but within a year he had Geta assassinated. In 217, after years of viciousness, he too was assassinated when one of his bodyguards killed him while he was urinating at the side of a road. Severus and Antoninus-Caracalla had father-son problems, to say the least, and so it was likely that the son would oppose his father just because he

was his father. This conclusion is buttressed if those who adhere to the conventional wisdom are wrong about the name Caracalla.

The nickname Caracalla is said to have been given to Antoninus after he arrived in Britain. It is said to mean “Gaulish Cloak” and to have been given to him because he popularized a particular type of heavy-hooded cloak favored by the Gauls. This seems unlikely. It is hard to picture tough legionaries, talking among themselves about their Emperor’s son, saying, “Here comes old Gaulish Cloak.” (The Windsor tie-knot was named for the frightful Duke of Windsor. No one who saw him approaching ever said “Here comes old tie-knot.” They probably said, “run.”)

Antoninus was a playboy and probably a dandy. He may even have dressed eccentrically just to annoy his strict, military-minded father. It seems likely however that there would have to have been more to a nickname to make it stick than the mere fact that a man wore a certain type of cloak. In any event, wearing a Gaulish cloak among Celtic people would have been unremarkable, and popularizing a warm Gaulish cloak in the heat of Rome, uncomfortable. This Gaulish Cloak explanation for the name Caracalla does not make sense.

It is more likely the name Caracalla had a more sensible meaning, a meaning that is clear if the matter is approached from a Scottish point of view. I took the

Calla

suffix to be relevant to the Caledonians, the collective name by which the Romans called the Pictish people who lived north of the Antonine Wall.