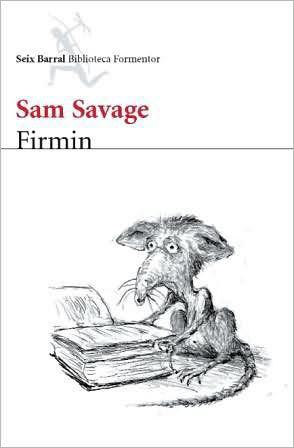

Firmin

Authors: Sam Savage

Tags: #Rats, #Fantasy Fiction, #Fiction, #Books and Reading, #Fantasy, #General

| Firmin | |

| Sam Savage | |

| Seix Barral (2007) | |

| Rating: | **** |

| Tags: | Rats, Fantasy Fiction, Fiction, Books and Reading, Fantasy, General |

Firmin: Adventures of a Metropolitan Lowlife (2006) is the second novel by author Sam Savage, about a rat runt in 1960s Boston who learns to read. Read more - Shopping-Enabled Wikipedia on Amazon

In the article:

Plot summary

Savage's sentimental debut concerns the coming-of-age of a well-read rat in 1960s Boston. In the basement of Pembroke Books, a bookstore on Scollay Square, Firmin is the runt of the litter born to Mama Flo, who makes confetti of

Moby-Dick

and

Don Quixote

for her offspring's cradle. Soon left to fend for himself, Firmin finds that books are his only friends, and he becomes a hopeless romantic, devouring Great Books—sometimes literally. Aware from his frightful reflection that he is no Fred Astaire (his hero), he watches nebbishy bookstore owner Norman Shine from afar and imagines his love is returned until Norman tries to poison him. Thereafter he becomes the pet of a solitary sci-fi writer, Jerry Magoon, a smart slob and drinker who teaches Firmin about jazz, moviegoing and the writer's life. Alas, their world is threatened by extinction with the renovation of Scollay Square, which forces the closing of the bookstore and Firmin's beloved Rialto Theater. With this alternately whimsical and earnest paean to the joys of literature, Savage embodies writerly self-doubts and yearning in a precocious rat: "I have had a hard time facing up to the blank stupidity of an ordinary, unstoried life."

(Apr.)

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Firmin

SAM SAVAGE

Orion

A PHOENIX PAPERBACK

by Weidenfeld & Nicolson

First published by Coffeehouse Press, Minneapolis,

Minnesota, USA

© 2007 Editorial Seix Banal, Av. Diagonal 662-664,

080304 Barcelona

This paperback edition published in 2008

by Phoenix,

an imprint of Orion Books Ltd,

Orion House, 5 Upper St Martin’s Lane,

London WC2H 9EA

An Hachette Livre UK company

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Copyright © Sam Savage 2006 Illustrations © Michael Mikolowski 2006

The right of Sam Savage to be identified as the author of

this work has been asserted in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in

any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior

permission of the copyright owner.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This ebook produced by Jouve, France

dreamed that he was a butterfly, flying happily about.

And this butterfly did not know that it was Chuang

Tzu dreaming. Then he awoke, to all appearances

himself again, but now he did not know whether he

was a man dreaming that he was a butterfly or a

butterfly dreaming he was a man.

The Teachings of Chuang Tzu

been one word: Myself.

Philip Roth

had always imagined that my life story, if and when I wrote it, would have a great first line: something lyric like Nabokov’s ‘Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins’; or if I could not do lyric, then something sweeping like Tolstoy’s ‘All happy families are alike, but every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.’ People remember those words even when they have forgotten everything else about the books. When it comes to openers, though, the best in my view has to be the beginning of Ford Madox Ford’s

The Good Soldier

: ‘This is the saddest story I have ever heard.’ I’ve read that one dozens of times and it still knocks my socks off. Ford Madox Ford was a Big One.

manfully -

as with openers. It has always seemed to me that if I could just get that bit right all the rest would follow automatically. I thought of that first sentence as a kind of semantic womb stuffed with the busy embryos of unwritten pages, brilliant little nuggets of genius practically panting to be born. From that grand vessel the entire story would, so to speak, ooze forth. What a delusion! Exactly the opposite was true. And it is not as if there weren’t any good ones. Savor this, for example: ‘When the phone rang at 3:00 a.m. Morris Monk knew even before picking up the receiver that the call was from a dame, and he knew something else too: dames meant trouble.’ Or this: ‘Just before being hacked to pieces by Gamel’s sadistic soldiers, Colonel Benchley had a vision of the little whitewashed cottage in Shropshire, and Mrs Benchley in the doorway, and the children.’ Or this: ‘Paris, London, Djibouti, all seemed unreal to him now as he sat amid the ruins of yet another Thanksgiving dinner with his mother and father and that idiot Charles.’ Who can remain unimpressed by sentences like these? They are so pregnant with meaning, so, I dare say, poignant with it that they positively bulge with whole unwritten chapters - unwritten, but there, already there!

good

. I could never live up to them. Some writers can never equal their first novel. I could never equal my first sentence. And look at me now. Look how I have begun this, my final work, my opus: ‘I had always imagined that my life story, if and when ...’ Good God, ‘if and when’! You see the problem. Hopeless. Scratch it.

cannot

begin, where the stream is already in full flood.

Pursuit and Escape in America’s Oldest Cities

. In the scramble of her panic she had managed to get all the way around behind the curved metal thing, so that only a faint glow reached her from the lighted basement, and there she crouched a long time without moving. She closed her eyes against the pain in her side and focused her mind instead on the delicious warmth of the cellar that was rising slowly through her body like a tide. The metal thing was deliciously warm. Its enameled smoothness felt soft, and she pressed her trembling body up against it. Perhaps she slept. Yes, I am sure of it, she slept, and she woke refreshed.