Forensic Psychology For Dummies (28 page)

Read Forensic Psychology For Dummies Online

Authors: David Canter

The frustrations of a need-to-know basis

In one case I was asked to assess the written material of a man who was accused of killing his wife. I wanted to talk to him in person to get to understand more of his way of thinking about things, but because the prosecution had called me in, the defence wouldn’t allow me to talk to him.

From the other side, when called in by the defence in a suspicious suicide, I wasn’t allowed to interview prosecution witnesses who knew the deceased, and who may have helped me understand the victim’s mental state. By denying me that access, the prosecution made sure that my opinion wouldn’t be put before the jury.

Criticising the role of forensic psychology experts in court

Some people have raised the following criticisms about the use of forensic psychologists as experts in court:

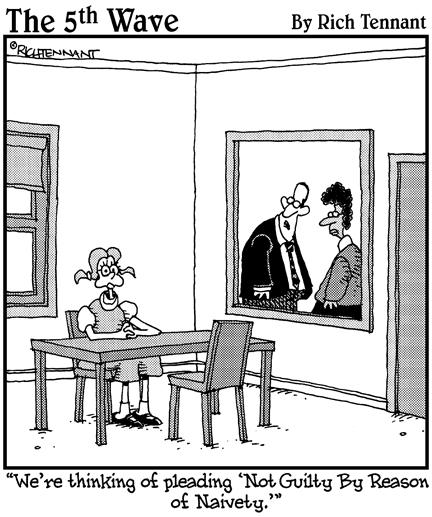

Their opinions are so powerful that they inappropriately dominate the legal proceedings.

They can offer opinions on the ‘ultimate issue’, something that the court should determine.

They’re biased by the financial incentives of giving evidence (experts are paid for their time, often quite handsomely).

They may have professional relationships with defendants or witnesses that are external to the court process, for example, through therapy or consultancy.

They’re under pressure from the lawyers to offer evidence that suits their side of the case.

They can fall into the trap of competing with an opposing expert and so overstate their case.

They may display a lack of awareness of sources of bias in the evidence.

Part II

Helping the Police Solve Crimes

In this part . . .

Sometimes psychologists move into areas that most people think are really the provenance of the police; interviewing witnesses, deciding if a suspect is lying, helping victims or even considering how to prevent crime. The role in this area that has caught the public imagination is ‘offender profiling’, which is usually presented as some almost magical skill of a gifted individual. In all of these areas psychological processes can help the police to be more effective. In this part the psychological theories and methods that underpin these contributions are described and I blow away some of the myths that fiction writers live by.

Chapter 4

Interviewing Witnesses and Victims

In This Chapter

Grasping the importance of witness interviews for the law

Understanding how memory works and how it can err

Creating more effective interviewing

Handling the eyewitness challenge

Handling the eyewitness challenge

Committing a crime and not being detected is thought of as the perfect crime (well, at least in crime fiction). Until someone reports a crime it doesn’t appear on the radar. Seeing the report of a crime on TV you’re always given what appears to be a clear picture of what’s happened and when. Yet even a video recording of a crime is open to interpretation. For example, in the UK people have been shot because a police sharpshooter claims to have seen a gun, but none is later found. Or, you come home to find that your home has been burgled and everything is upside down but the nature of the crime is open to question until you can give an accurate description of what’s been taken. At every stage of the legal process a description of what’s actually happened is required, usually, by a witness or witnesses making a statement to the police or lawyers. But it can also be a suspect being interviewed and being asked where he was and what he was doing at the time of the crime.

In this chapter, I walk you through the psychology of interviewing people as part of an investigation (talking to a patient in therapy, for example, is something quite different). When a witness has seen something or someone they may be asked to identify the object or person. I also consider this eyewitness testimony. I don’t worry in this chapter about the complicating factor of deliberate lying and deception (something I cover in Chapter 5). I discuss the process and experience of interviewing witnesses, suspects and victims by investigators. Interviews are accounts of what people remember. So I also examine how human memory works, including the ways in which memory can be unreliable, and I describe the issues of helping people remember what may be traumatic incidents, particularly when the person is very distressed.

Understanding the Nature of Interviews: Why Are You Asking Me That?

Interviewing is all about getting an accurate account of an event. But when the police interview someone, they want to do more than just find out what’s actually happened. They also need to find answers to the questions:

Is the incident a criminal offence?

Where can I find further evidence?

Are there any other witnesses or victims?

How does this witness’s account coincide with any other witnesses?

Did the victim contribute to the crime in any way?

Are the victims or witnesses telling the truth?

Clearly, the interview is much more than a chat between friends. The recording of the interview – whether a written account or an audio or video recording – is a legal document that many people draw on. Forensic scientists will use it to see if it points to where there may be evidence. If a victim says ‘he grabbed my sleeve’ then the scientists know to look closely there for DNA. The defence and the prosecution draw on the interview to prepare their cases for court.

The necessity of having a complete and accurate account of an interview was brought home to me once after interviewing a man charged with a serious crime. My object had been to get to know the suspect and find out as much as I could about his background to draw on for his defence. I had to provide the court with a full audio recording of the interview, but I turned the recording off immediately when the interview was over. This made the recording seem to stop suddenly. I therefore had to make clear that I had not deliberately cut out something that was relevant to the case.