Forensic Psychology For Dummies (63 page)

Read Forensic Psychology For Dummies Online

Authors: David Canter

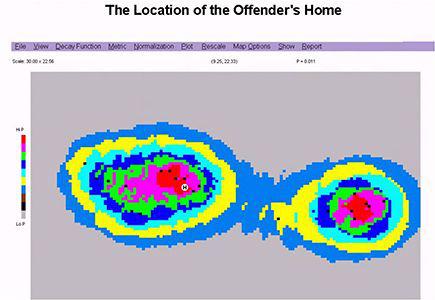

As an example, take a look at Figure 6-2, which shows the locations of bombs left in an extortion campaign across London. The points are the locations on a map of where the bombs were left. By looking at the distances criminals typically travel to commit their crimes, a computer programme calculates the likelihood of where on the map the bomber’s home could be, and then joins up the areas that have the same probability. This is like height contours on an ordinary map, but instead of height this map shows how probable it is that the offender is living in any location. The figure shows two areas that have high probabilities, one to the East and one to the West. The police put surveillance on ATM points in the West and caught the culprit, Edgar Pearce, who lived near to where he was caught. The high probability area to the East surrounds where his ex-wife lived, who he still visited.

Figure 6-2:

A map showing

the locations of bombs left in the London extortion campaign.

Distinguishing between Crimes

Crucial to ‘profiling’ an offender is gaining an understanding of the type of criminal acts that the person carries out. Therefore, as part of ‘profiling’ offenders directly (a subject I cover in the earlier sections of this chapter), forensic psychologists have to examine and understand the different sorts of crimes that people commit, identifying the distinguishing characteristics of a crime: for example, the willingness (or not) of a person to use violence is central to making an investigative inference. Doing so requires an understanding of how crimes that notionally appear similar (and may even have the same legal label) differ from each other in important behavioural ways.

Of course, certain basic aspects remain common across most crimes of a certain type (a burglary involves stealing from a property, a rape involves a sexual assault). But the forensic psychologist needs to be able to distinguish more subtly between crimes, identifying the

less

common indicative actions of different styles of behaviour.

The advance fee fraud

You’ve probably received an e-mail (or in the olden days a fax or even a letter), or know someone who has, that says millions of dollars exist in some account and you can have a goodly proportion of it if you co-operate with the sender. It may be explained that the money is in a bank account because the original account holder has died and there are no relatives, or any of a number of other marginally plausible reasons.

If you respond to this offer of these windfall millions, you’re asked for a relatively small sum of money to set up an account, to bribe someone, or for some other reason. This is the ‘advance fee’ that gives the fraud its name.

If you’re rash enough to provide some initial fee, you’re then asked for more money and yet more. Experts estimate that people who get sucked into this trap can lose on average as much as $30,000 before they realise that they’ll never see any of their money or anyone else’s ever again. Some people try to follow this up by direct contact with the fraudsters, who then become threatening and violent. Some authorities claim that a number of otherwise unexplained murders occur each year of victims trying to get their money back.

Dealing with property crimes

Experts often use the technical term

acquisitive crime

to describe all those crimes in which something of value is taken without permission of the owner. In such cases the owner is always directly or indirectly caught up in the crime. So the most crucial difference between crimes is whether only property is taken or a victim is confronted by the criminal. This distinction between property crimes and person crimes is central to understanding criminal actions.

The consistency principle that I describe earlier in this chapter (in ‘The railway murderer’ section) draws attention, for instance, to familiarity and the typical way of dealing with other people that you’d expect to be common in criminal and non-criminal situations. Consequently, whether the offender engages directly with the victim or avoids such contact has key psychological implications.

Within the category of acquisitive crime, a wide range of variations exists. For example, a span of scenarios can be identified, from having contact with the victim (as is characteristic of robbery), through burglary (in which the victim may or may not be present), through to the modification of documents in which no direct contact is ever made (as may be the case in many frauds). This set of stages implies a reduction in the willingness to use physical threats to obtain the property and an increase in the skills of manipulation of opportunities.

Forensic psychologists need to proceed with caution, though, because many combinations are possible. For example, some fraudsters start off very distant from their victims, but having made contact can start using threats of violence as in the nearby sidebar ‘The advance fee fraud’.

Fraud

Broadly speaking, people become major fraudsters through one of two dominant routes: they spot loopholes in systems and then gain access to them in order to obtain vast sums of money; or they’re in a position of trust and find that they need some money, which isn’t readily available from personal funds. You may be surprised to discover that the first group is in the minority. Notorious examples such as Frank Abagnale do exist (see the nearby sidebar ‘Catch me if you can . . . oh, you did!’), but they’re extremely unusual.

The more usual way in which serious fraud happens is that a person abuses a position of trust and, say, steals from a company or organisation. Sometimes the person has gambling debts or just a desire for the good life, but very often the theft is to save face in unexpected financial circumstances.

One fraudster said that his business collapsed when apartheid suddenly came to an end in South Africa. He employed many people and didn’t want them to lose their jobs. He therefore took a little money from a source he shouldn’t have, hoping that the business would get better and he could pay it back. But things got worse and he took more money. Eventually he’d acquired £50,000 fraudulently before he was caught.

Forensic psychologists know that this sequence of small betrayals of trust leading to bigger and bigger fraud until it gets out of control is a common pattern.

Catch me if you can . . . oh, you did!

The most successful US fraudster ever was Frank Abagnale, who cashed $2.5 million in bad cheques across 26 countries over five years. Before he was 20 years old, he managed to impersonate an airline pilot well enough to be allowed to travel on over 250 flights for free and pass himself off as a sociology professor, doctor and attorney. He was eventually caught but allowed out of prison on condition that he help the FBI catch other fraudsters. Eventually he became a millionaire legitimately through advising companies on how to detect and avoid fraud. His story was made into the movie

Catch Me If You Can

in which Leonardo di Caprio played Abagnale brilliantly.