Framingham Legends & Lore (15 page)

Read Framingham Legends & Lore Online

Authors: James L. Parr

Nineteenth-century magazine advertisement for Chubb fishing rods.

Courtesy of James L. Parr

.

T

HE

“B

ATTLE

H

YMN OF THE

R

EPUBLIC

”

During the nineteenth century, Washington's Birthday was a holiday celebrated with nearly as much patriotic fervor as Independence Day. Parades, fireworks, military displays and speeches were all popular forms of entertainment on February 22 each year.

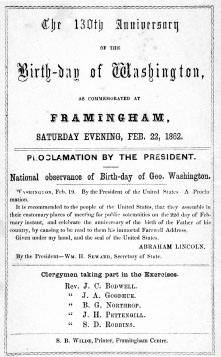

The 130

th

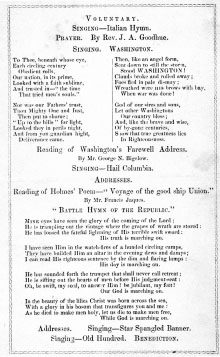

anniversary of Washington's Birthday in 1862 took on new meaning as the nation was nearing the end of its first year in the Civil War. A proclamation by President Lincoln urged Americans to include in their public observances a reading of Washington's farewell address to his troops. Framingham's program was held at the Plymouth Congregational Church on the town common, with Normal School principal George Bigelow reading the Washington speech. Several poems and hymns were also included in the program, one of them a stirring tribute and call to victory for the Union entitled “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” written by Julia Ward Howe and recently published in the

Atlantic Monthly

. At the end of the program, for the first time in public, Howe's lyrics were sung to the now familiar and often parodied tune. Little did the audience in Plymouth Church know the depth of meaning that would later become attached to this song as the war dragged on for three more years.

The melody to which Howe set her lyrics is said to have come from the camp meeting circuit of the early 1800s. The tune had earlier been appropriated by soldiers of the Massachusetts Militia stationed at Fort Warren on George's Island in Boston Harbor. When a fellow soldier named John Brown died while stationed at the fort, his comrades invented various lyrics to the old tune in tribute, one of the lyrics being “John Brown's body lies a-mouldering in the grave.” The song and its new lyrics became popular in Boston, where Julia Ward Howe was living at the time. Many residents mistakenly believed the song to be about the abolitionist John Brown, who had been arrested and executed for his raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia. In true folk-tune tradition, new verses were anonymously added and passed on.

Cover of 1862 program that featured the first public singing of the “Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

Page from 1862 program with words to the “Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

While touring army camps with her husband in Washington in November 1861, Julia Ward Howe and her companions were heard singing the John Brown song with some of the Union soldiers. A friend suggested she write new lyrics to the tune, and the next morning Mrs. Howe dashed off the lyrics in one sitting, knowing even then that something special had just been created. The song became a national anthem for the war effort and was revered to the point that, in 1863, a New York school principal was fired for refusing to sing the song with her students as directed by the school board.

Julia Ward Howe made several appearances in Framingham after the war, including the recitation of a poem to a crowd of two thousand suffrage supporters gathered at Harmony Grove in 1874. In June 1900, Mrs. Howe was invited to speak on the subject of character during a celebration of the town's 200

th

anniversary held at the Grace Congregational Church on Union Avenue. During the program, a group of schoolchildren had the unique privilege of singing the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” to an audience that included the song's author, in the same town where it had first been sung publicly thirty-eight years earlier.

A B

RAND

-

NEW

F

RAMINGHAM

By the end of the Civil War in 1865, Framingham had been transformed into a completely different town than it had been at the dawn of the nineteenth century. Not only had its population almost tripled since 1800âfrom 1,625 to 4,665âbut it had grown much more diverse, with new Irish Catholic immigrants added to the old Yankee population. It was now a town of railroads and turnpikes, with two industrial villages at Saxonville and South Framingham that had not previously existed, and even the relatively sleepy Centre was a much more dynamic place. The explosive growth would only accelerate over the next forty-five years as the population reached 12,948 by 1910 and included even more new immigrant groups from Southern and Eastern Europe. But the pattern for this growth had already been established.

Chapter Six

REFORM AND RECREATION

Framingham in the Victorian Era

T

HE

I

NDOMITABLE

S

PIRIT OF

R

EFORM

The reform spirit that had fed the abolitionist movement did not entirely dissipate after the Civil War. Instead, the energy was fed into new movementsâtemperance, women's suffrage, prison reform, education and religious enlightenment, among many others. If the business of Framingham undoubtedly remained business during the Victorian era, this chapter will examine a different side of the community, one striving for moral improvement or diversion, sometimes both at the same time. The reader may rest assured that we will get back to business in the next chapter.

T

HE

S

HERBORN

R

EFORMATORY

The facility that is today known as the Massachusetts Correctional InstituteâFramingham began its life in a different town with a different name. Originally known as the Massachusetts Reformatory Prison for Women, it was established in the town of Sherborn in 1877. When the town of Framingham annexed 565 acres of north Sherborn in 1924, it also acquired the women's prison and its colorful history.

The Sherborn Reformatory was the first women's prison in the country, begun by social reformers with the intent of actually changing the lives of its inmates rather than merely incarcerating them. To accomplish this mission, the women were put to work on the four-hundred-acre farm that surrounded the imposing brick prison building. A variety of vegetables and grain crops were grown, and pigs, cows, sheep and poultry were also raised. For a time, the inmates raised silkworms, which spun their cocoons in the 128 mulberry trees planted expressly for that purpose. A shirt-making industry was also operated on the grounds. Receipts from the sale of the prison's products were used to cover operating expenses.

Sherborn Reformatory (now MCIâFramingham) in a nineteenth-century view.

Another crucial component of the inmates' reformation was the grading system used to encourage and reward hard work and good behavior. Upon entering the institution, inmates were assigned a grade, or division, from one to four. Inmates in the higher divisions were given more comfortable rooms and privileges, such as letter writing and tea taking. Some inmates in Division 4 were sent out to work as domestics in local homes. A point system, much like a report card, was used to keep track of an inmate's progress, allowing her to gain more privileges as she moved up through the divisions.

One of the first superintendents of the reformatory was Clara Barton, founder of the American Red Cross. Miss Barton had been deeply immersed in her Red Cross work in the spring of 1883 when the governor of Massachusetts, retired General Benjamin Butler, asked her to take over the superintendent's position. Although she was reluctant to leave her Red Cross mission, Barton felt a fierce loyalty to Butler, who had strongly supported her as she ministered to the wounded and dying on the battlefields during the Civil War. After taking a tour of the facility, she agreed to take the position, but only for six months. Although the facility had been open for only six years at the time Barton took over, it had already earned a national reputation as a model for reform. Clara Barton's short stewardship only reinforced that reputation.

Her tenure there was marked by kindness and empathy toward the women, many of whom she viewed not as criminals but as victims of poverty, alcohol and the social double standards of the time. She treated them with a respect and human dignity they had never experienced before. Her reputation as the “Angel of the Battlefield” during the Civil War inspired awe in the prisoners who met her as she walked the hallways and gave talks in the chapel. Upon their release, many inmates tearfully promised her they would turn their lives around. Barton also made improvements to the prison's educational, governmental and business systems. She stayed two months longer than she had agreed to, returning to the American Red Cross in early 1884.

Barton was succeeded by Mrs. Ellen Johnson, who held the post for fifteen years until her death in 1899. Despite several unfortunate incidents over the years, including a series of prisoner riots in 1888, Johnson ran the reformatory with efficiency and compassion and is remembered as one of the most successful and innovative reformers of the nineteenth century.

C

ATTLE

A

NNIE AND

L

ITTLE

B

RITCHES

Two of the reformatory's most notorious residents arrived in the fall of 1895 from the wilds of Oklahoma. Anna McDoulet and Jennie Metcalf, better known as “Cattle Annie” and “Little Britches,” were only fifteen years old, but they were already experienced criminals. As members of the Bill Dalton outlaw gang, the tobacco-chewing, gun-toting teens stole horses, sold whiskey to the natives and acted as lookouts during robberies. Jennie was arrested after a shootout in which she easily handled a pair of massive six-shooters. Because of their youth, both girls received relatively light sentences of two years at the Sherborn Reformatory, where they would learn “womanly duties” and “get accustomed to the civilized, proper style of life.” Their arrival in Sherborn brought crowds of people to the prison gates, hoping to get a glimpse of the “Oklahoma Girl Bandits” at work in the fields. After spending about a year farming, doing laundry and other chores, the girls were released, having turned their lives around at Sherborn. Although there are conflicting accounts of their lives after they were released, their criminal careers were well behind them. The girl outlaws remain a part of Wild West lore to this day. In 1981, Hollywood produced a movie loosely based on their adventures called

Cattle Annie and Little Britches

, starring Diane Lane, Amanda Plummer and Burt Lancaster.

T

HE

C

HAUTAUQUA

A

SSEMBLIES AT

L

AKEVIEW

The names Mount Wayte, Methodist Campground, New England Chautauqua, New England Sunday School Assembly and Lakeview all refer to the hilly area located to the northwest of Farm Pond. Originally named for Richard Wayte, the Boston resident who was granted three hundred acres by the Bay Colony in 1658, we recall it as the site of the infamous Eames massacre of 1676, as related in

Chapter One

. Nearly two hundred years later, in 1871, the Methodist Church purchased forty-five acres and established a summer campground there, which they named “Lakeview.”

Camp meetings were a popular summer diversion offered since the early 1800s, gaining in popularity after the Civil War. The first camp meeting at Lakeview began rather humbly in August 1872, with five hundred participants staying in tents and attending daily scripture readings, prayer services and hymn sings. By the next summer, several wooden cottages had been built and the facility included mail service, a bookstore and a barbershop. Over the next few years, both the crowds and the campus grew, and in 1880, the first meeting of the New England Chautauqua Assembly took place. The Chautauqua Movement was begun in 1874 by two Methodist ministers who intended to advance the social, physical, moral and intellectual lives of its members. The name came from New York State's Lake Chautauqua, where the first assembly took place. Assemblies were held each summer across the country, and the campground at Lakeview was the headquarters for the New England Assembly.