From Baghdad To America (13 page)

Read From Baghdad To America Online

Authors: Lt. Col. USMC (ret.) Jay Kopelman

My first meeting with Dr. Wood is at the offices of VRMC. They're located in a sprawling office park here in San Diego, not unlike so many other clusters of three-story steel, glass, and concrete buildings housing medical, high-tech, and real estate offices. There's no guard in the lobby, just the directory on the wall, pointing visitors to any number of nondescript doors leading to generic, unpretentious office suites. We meet in a conference room. I'm able to ask Dr. Wood some questions about PTSD and the application of VR to treat it. He enlightens me that afternoon, whetting my appetite for more information and an opportunity to see the system at work.

My curiosity getting the better of meâand because I do have a vested personal interest in finding outâI ask the doctor if there is anything that predisposes a person to suffer PTSD. He tells me that there are indeed indicators:

- Genetic markers

- Multiple or single trauma(s) during the developmental years

- Lack of resilience training (essentially introducing stress-inducing types of events likely to be encountered) during the pre-deployment period (Here Dr. Wood relates to me the history of one sailor diagnosed with PTSD who was assigned to work with Army special forces in Afghanistan and who ultimately saw firsthand horrifying brutality by the Taliban, for which he was not prepared.)

- Constant arousal. (Not

that

kind, you creepsâsay, mortar and rocket shelling.) - History of psychological difficulties and/or alcohol or drug abuse, sometimes brought on by post-deployment self-medication to ease the pain

- Unit cohesionâhow accepted does the new guy feel? For women, sexual harassment or not being perceived as integral to success in combat makes for particular susceptibility to PTSD.

It's funny, but by these markers, Lava's personality doesn't seem such a PTSD slam-dunk. Then again, Lava's trainer, Graham, mentioned genetic markers, too, and pointed out that Lava was not exactly the product of an AKA-certified stud. Chances are that his father, and a few fathers before him, were essentially feral.

Following our conversation, Dr. Wood takes me around the offices of VRMC to introduce me to some people, including the founder, Mark Wiederhold, M.D., Ph.D. The offices are unremarkableâthey could belong to any number of businesses, from an erectile dysfunction treatment clinic to a penny-stock boiler-room operationâexcept the work being done here is infinitely more important to society.

Then it's time to see the VR room. It's not the full-blown dogand-pony show I hoped for, because the equipment and manpower to monitor my reactions aren't available, but it's interesting to see and experience the scenarios nonetheless.

The computer software is very realistic, and as I go through the scenariosâa grunt on the ground searching out bad guys; a turret gunner in a convoy complete with an insurgent technical (a pickup truck with a machine gun in the back); an observer in a virtual FallujahâI try to monitor myself for the markers the technicians and psychologists use to monitor a patient's progress or levels of anxiety: elevated respiratory and heart rates (levels of arousal).

Had I been hooked up, Dr. Wood would have been able to accurately monitor my respiration, heart rate, peripheral temperature (finger temperature, which is normal at around ninety-two degrees Fahrenheit and drops when the fight-or-flight instinct kicks in), and galvanic skin response (sweaty palms), which is graded on a scale of one through ten, one being normal. These inputs are used to give the clinician an indication of the level of anxiety a patient is experiencing at any time and allow him or her to talk the patient down.

The patient can then practice any of the relaxation techniques he is taught or simply remove the VR headset. One of the relaxation techniques Dr. Wood describes is the “

Happy Gilmore

happy place.” That is, you imagine yourself in a situation that brings you comfort and safety, as Adam Sandler's character did to calm his nerves on the golf course in the movie

Happy Gilmore

.

Dr. Wood and his team published an article about their success thus far, although it's still quite new. All six of the patients treated reported less anxiety and depression after ten sessions in the program.

15

16

The potential for VR in PTSD prevention and treatment is really unlimited. The problem lies in getting warriors to use it. And there's the rub. An example of what the military has traditionally done to assess Marines' or soldiers' likelihood of developing PTSD following a combat deployment is to give them those PDHAs to fill out, seeking answers to questions such as where they were deployed; their assessment of their own emotional health; their exposure to combat, specifically blast or explosion, vehicle accident, and fragment wound above the shoulders (all checking for a possible traumatic brain injury, or TBI); whether or not they saw dead bodies; and if they ever felt in danger for their lives. What? It's combat these folks are in. If they didn't feel in danger for their lives, I'd have to really wonder.

Here's what happens, though. Marines, soldiers, and sailors fill in this assessment in Iraq or Kuwait immediately before coming home. These kids have been looking forward to coming home since they got on the plane to deploy. But wait. Here comes the good part: The box containing all the PDHAs is lost. The warriors come home and plan to spend a few days away from the unit in the loving embrace of their families. Not so fast, bucko! You don't go anywhere until the PDHAs have been completed. So you sit in a set of bleachers with a staff sergeant or gunnery sergeant yelling at you to hurry up, and oh by the way, you'd better not answer yes to any of the tough questions or no one goes anywhere. Get the picture?

Despite the possibility of things going undetected with this system, the numbers are staggering. Of the Marines in Iraq, the following reported percentages reflect their combat experiences:

95 percent attacked or ambushed

92 percent received incoming artillery, rocket, or mortar fire

97 percent shot at or received small-arms fire

87 percent shot or directed fire at the enemy

65 percent responsible for the death of an enemy combatant

28 percent responsible for the death of a noncombatant

94 percent saw dead bodies or human remains

And the relationship between Marines' combat experience and PTSD is clear with the support of even more overwhelming numbers. Of deployed soldiers and Marines, the prevalence of PTSD increased with the number of firefights; 4.5 per cent for no firefights, 9.3 per cent for one to two firefights, 12.7 percent for three to five firefights, and 19.3 per cent for more than five firefights. (16)

If the DoD had the sense to use VRâspecifically the scenarios currently being used by VRMC to assess our warriorsâthen we could virtually forgo the use of the PDHA and more accurately determine an individual's susceptibility to PTSD. Treatment could begin immediately. We could train our heroes to modify their behavior in order to live happier and more fulfilled lives as civilians before it's too late.

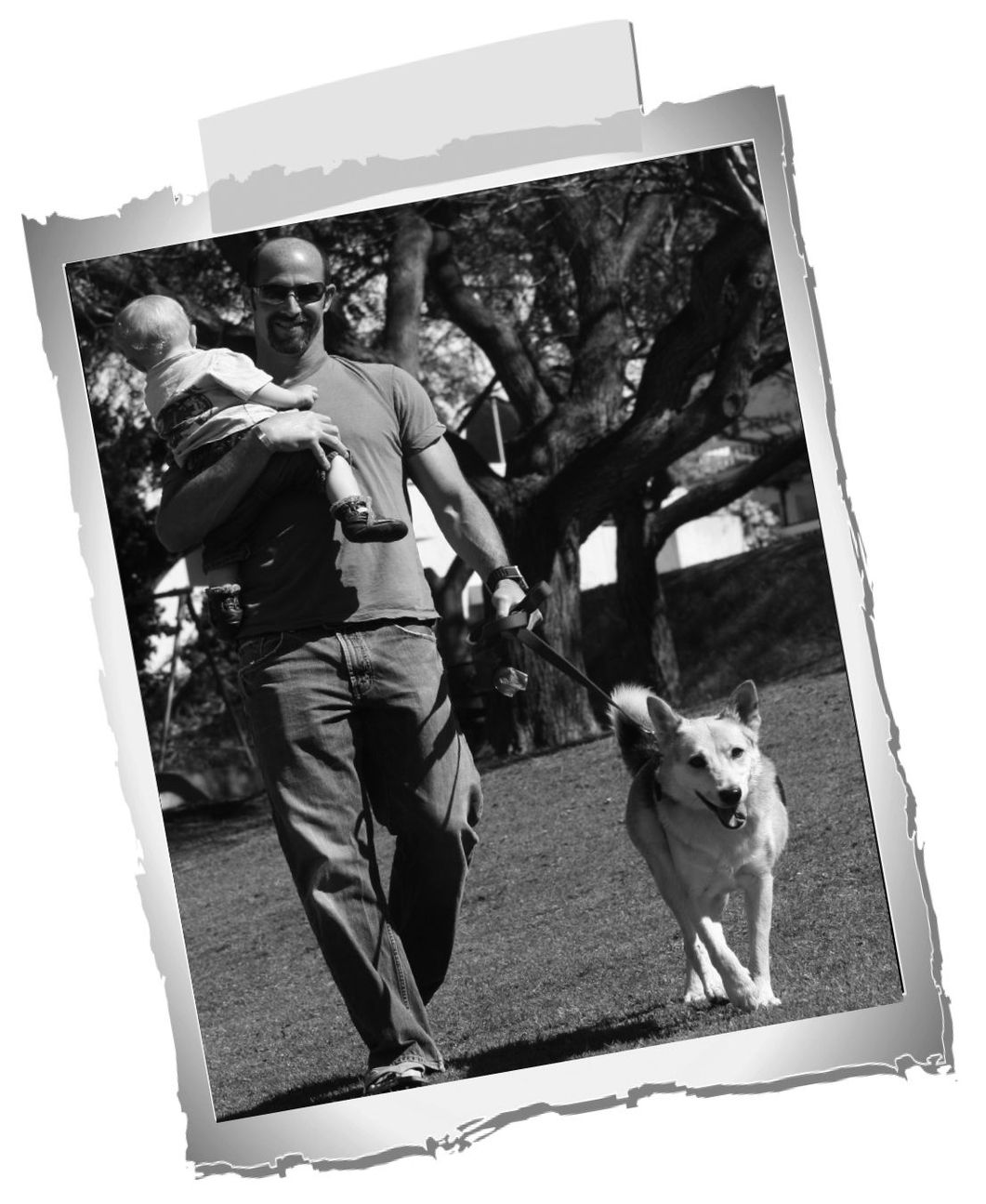

LTC Kopelman,

I was deployed to Iraq as a civilian contract fire lieutenant from August 2004 to August 2005, spending the first 8 months at Logistical Support Area (LSA) Anaconda in Balad.

While I was at Anaconda I discovered a black dog living outside of the security fence. “Black Dog” was a stray, literally living under one of the guard towers outside of the wire. I am pretty sure that the soldiers in the tower were feeding the dog on a regular basis, and of course we would often stop on our way back to the fire house from the dining facility and heave some leftovers to Black Dog. I also had some family and friends send me some large dog chew bones in my care packages. I would send the chew bones up to the guards in the tower and they would give Black Dog these treats from the States.

I knew of a National Guard unit who had rescued two stray dogs from LSA Anaconda, so naturally I thought I might be able to do the same for Black Dog. Any rescue would be a long shot because unlike Miss Sippy and Rex, who both lived on the base and were rescued by a Mississippi National Guard unit, Black Dog lived outside of the wire and had never been socialized with humans. His only interaction was by the food that dropped out of the sky from the guard tower.

“Black Dog” outside the fence of Camp Anaconda in Balad, Iraq

My plan was to have the Quick Reaction Force pick up the dog, take him to the installation vet for a quick physical, and then fly him to Kuwait on an army aircraft. Although I had talked to most of the parties who would be involved in the rescue, my plan hit a snag when our entire civilian fire department was shipped to another army base in Iraq. Before I left, I took a few pictures of Black Dog and bid him farewell.

Hopefully, Black Dog is still living under the tower on a diet of DFAC food supplied by the soldiers in the tower and other dog lovers.

I was saddened that I could not help Black Dog, but hearing about soldiers and Marines who were successful in bringing some kindness and caring to the many Iraqi dogs (and cats) warms my heart. Thank you for rescuing Lava from a dismal life and thank you for your service to our country.

Dennis Donehoo

NEVER QUIT

“There was one catch and that was Catch-22. Orr would be crazy to fly more missions and sane if he didn't, but if he was sane he had to fly them. If he flew them he was crazy and didn't have to; but if he didn't want to he was sane and had to.”

â

JOSEPH HELLER

,

CATCH-22

I've learned about the different kinds of therapy,

but I suspect that whatever I do someone is going to ask me about my father. I've made the first call but waiting is no good, so I look again at the list I have. What if these guys are complete dicks? What if they spend their Thursday nights tasting wine in Sonoma? Then what?

My appointment day at the VA Mood Disorder Clinic arrives and naturally I'm apprehensive. I mean, I'm entering uncharted territory here. What will it be like? Will I be in a waiting room with a bunch of drooling, babbling Vietnam-era veterans, wearing their field jackets with all the patches on them à la

The Deer Hunter

? Adding to my newfound anxiety is the fact that parking is abysmal. I drive around the VA lot (angrily, of course) for twenty minutes, which makes me late, which fuels my anxiety.

Fuck, fuck, fuck all to hell!

When I finally get to Second Floor North (where the outpatient loonies wait for their appointments) to sign in, I notice a rather full waiting room, which suggests to me that there are a whole slew of vets in need of help. This doesn't bode well for the young kids who will one day come home from Iraq and Afghanistan markedly different from the carefree twenty-somethings they were before they went to war.

Going to your therapist is different from going to the regular doctor. They don't take your vital signsâI guess it wouldn't tell them anything. You can appear to be calm and centered with a low, steady pulse, but if you're ready for a straitjacket and a room with padded walls you could crack at a moment's notice. No, temperature and blood pressure aren't being checked this day. You sign in at a desk as usual, and you sit and wait as usual, but the nurses and administrative staff who go about their daily business don't look at you like you're just there for a routine appointment. This look is more guarded, almost pitying. Like,

Wow, you poor bastard, I feel so bad for you with what you must have going on in your scrambled-up head. And it's a shame, too, because you don't really

look

deranged or anything. In fact, you're kind of attractive, and I might even talk to you under other circumstances, but we all know why you're here, so please don't even glance at me.

So I sign in, sit and read my bookâ

Jarhead

(what else?)âand wait to meet with my caseworker. He's a very nice gentleman who's been working at the VA for thirty-six years. (I know this because I feel it my obligation to interview him as much as he plans to interview me, and because I want to know my health care providers' credentials.) He either loves what he does or he gets some kind of perverse pleasure from hanging out around a bunch of nut jobs.

Hell, after thirty-six years of doing psychological inventories and writing evaluations, who's to say he's not completely wacked out himself, right? Oh yeah, these people who deal with the mumblers, screamers, and loonies every day, they try their best to treat you like anyone else they meet at a cocktail party, but there's this look they get when you tell them everything's really okay, that you're really just trying to do some research for your book.

That look of impending doom, that they know what a wack job you really are because only the true nuts and loons say everything is okay and they're really just doing book research when in reality (which gets very twisted and turned upside down) you're the biggest psycho since McMurphy in Ken Kesey's

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest,

and you're about to say, “I'm here to cooperate with ya a hundred percent. A hundred percent. I'll be just right down the line with ya, you watch. 'Cause I think we ought to get to the bottom of R. P. McMurphy.” Or, in this case, Jay Kopelman.

There's nothing comfortable or comforting about the questions I'm asked: “How's your relationship with your wife?” “How do you get along with your stepson?” “How does your obsessive-compulsiveness manifest itself?” “When did you first notice that you were having anger-management issues?” “Were you abused as a child?” “Were you ever sexually molested?” “Was your father nurturing?”

Hey, isn't that the mother's job?

I want to scream.

There's nothing fun at all about having your psyche probed with questions about abuse, molestation, and your father's ability (or lack thereof) to nurture. What have I gotten myself into? I thought this would be more about my military career. You know, “why did you join up?” “What did you hope to accomplish in Iraq?” “Was there anything you did that you really didn't want to do?” “Is there one incident that stands out in your mind?” I fully expected the “How did that make you feel” after each of my responses. But this personal stuff? What a fucking disaster.

So we have this conversation, the social worker and me. We talk of family and personal interests. I tell him that I'm a competitive cyclist and he tells me he has a son who's a competitive triathlete. We talk about tennis and the Australian Open and who we each think will win, shit like that. He then asks me if I have any questions before we part. “Uh, yeah, I was wondering, so what do you think? I mean, am I nuts, or what?”

“No, I think you're a perfectly normal, healthy adult,” he replies.

Uh-huh.

Why don't I believe you?

He tells me that they're going to call me to arrange five sessions. Yeah, right. More like five weeks' accommodations at the Ha-Ha Hotel. You check in, but you never check outâat least not as the same person you were when you voluntarily subjected yourself to the scrutiny of modern mind bending.

I get a call a few days later to schedule an appointment with a therapistâa social worker, actually, with a master's degree and some psychology backgroundâwho's good, I guess, at helping you modify behaviors that may be problematic if you're interested in staying married or having a good relationship with your children.

I know the day is coming, and I try to play it down by saying things to people I know like, “Yeah, my publisher wants me to go to this therapy thing so I can write about it, but there's really nothing wrong with me and I'll check it out and see what's going on so

other

peopleâpeople with

real

problemsâwill be helped by what I learn. I mean, I don't have any real issues, but those other people . . .” Man, do I have a lot to learn.

I get to the VA hospital for my appointment, and instead of going to the waiting room with all the normal loonies I have to go to the other end of the cuckoo floor. The end of the floor where the

real

crazies hang out. If this weren't so, there wouldn't be steel doors keeping everyone behind on constant lockdown.

This is when it hits me that someone, somewhere, thinks I am completely over-the-top stark raving mad. Why else would I be in this area with the controlled access? Only I'm confused because I don't hear the wailing, moaning, and ranting I expected. Maybe it's because they keep the patients so sedated they're incapable of any of the inherent maniacal behavior depicted in movies like

A Beautiful Mind

. No, there is no screaming, no steroid-infused orderlies running to restrain the violently delusional (at least not that I can see, but I know they're lurking just around the corner). There's only calm and quiet, and this is as unsettling to me as anything I expected to encounter.

My therapist is a very nice woman, with that look that's a mix of understanding and pity. Add in the practiced air of calm and serenity and not only do you feel comfortable about opening up, but you're ready to say things you'd never admit to anyone.

But I can't shake this feeling that the therapist is a scientist working with a bunch of wild monkeys. As long as she stays calm, the monkeys won't go completely ape-shit, thereby necessitating a call to the orderlies. I don't want to be the bad monkey. No one knows exactly where I am, and as long as my therapist (whom I'll call Sigmund even though she's a woman), holds the keysâliterally and figurativelyâthat will allow me to escape lockdown, I'm gonna be the good, calm, and cooperative monkey.

So in Sigmund's office we get to the nitty-gritty of why I'm here. “No, I don't have PTSD,” I tell her. “I'm doing research for my new book. My publisher thought it would be good for me to write a chapter about therapy so that other peopleâyou know, people who really need help, but are afraid to askâwill see that if a lieutenant colonel is going, it must be okay.” Leadership from the front, right?

“Well, Jay, is it safe to say that even though you're doing research for a book, maybe it would be possible that you're also here to help with some things you have going on? That you will be able to get some information for your book, but we can work on some things for you, too?” She says this in a voice so syrupy sweet that all I can think about is pancakes and French toast.

Huh? “Uh, sure, that sounds good. I mean, I would like to learn to be a better husband and father.”

“What do you mean, Jay?”

And that's when it starts. That's when you tell a complete stranger that you're a control freak, have anger-management issues, and cannot fathom for one second where anyone gets this sense of entitlement so prevalent in the civilian world. The questions about parents and childhood really start flying:

“Were your parents angry?”

“How angry?”

“How did that make you feel?”

“Were you ever afraid when you got in trouble as a child?” Answers: “Sometimes.” “Very.” “I don't know.” “No. What is there to be afraid of? A spanking? Big deal. No, I think some of my behavior is learned, though, from watching my parents, you know. I mean, if they could argue and yell, then that must be the way it's done, right?”

No answer from Sigmund. So you keep talking, then suddenly you realize that's what they want. They want you to divulge your secrets, like you pissed your pants as a child when you got yelled at and that will explain everything. Only you realize that if that's what they want it's not what you're going to give them. So you shut up and sit back and wait. (And, no, I didn't piss my pants when I got yelled at. Wouldn't you love to read that?)

But your silence only brings on more silence. Sigmund is practiced at this. I'm sure she's seen it before and she can sit and say nothing probably longer than I can, and the clock is ticking and I'm beginning to realize some things, and so I break. Beat me, freeze me, starve me, I ain't saying shit. But sit there in therapy across a desk from me with your yap closed and giving nothing until I give something first, and I'm like a frigging canary. I won't shut up. Why? What the hell is happening to me?

I want to ask her if I'm telling her what she really wants to know. What everyone who talks to me about the war wants to know.

Did you kill anyone?

In my first book, I hinted at it, gave a snippet about finding a baby in the rubble, but I've never addressed it face-on. Thinking about what I saw, about the war, makes me both exhausted and angry. Mostly it makes me want to concentrate on my beautiful family, which includes a gorgeous baby who will soon learn to walk and talk, a sweet preteen, a smart-as-a-whip beautiful wife who married me despite her father's warning, “It's not easy to be married to a military man.” I've always known my father-in-law was smart, and when he's right, he's right. He wasn't even taking into account my out-of-control, barely domesticated dog, fresh from the killing fields of Iraq.

If Lava were a man, no one would even question whether or not he needed to hightail it to the nearest psych ward. Lucky for me, he's not, and I'm his shrink. “Relax on the couch, Lava. Tell me about your father.” I have to mock it all, but the truth of the matter is this: Finding that little ball of fur and sharp puppy teeth has taken me on a journey I never expected. All the way to having my head examined. This I can reflect on while I sit with Sigmund. And she's back with more questions.

“Do you like to be in control?” “Does not having control of things frustrate you?” “How does it make you feel when you're not in control?” More answers: “Yes. Hey, I made a twenty-oneyear career out of being in control. You had to be in control, and everyone always knew who was in control.” “I don't know.” “What do you mean? You mean it's okay to feel?” Oh yeah, we're making progress now.