From Baghdad To America (15 page)

Read From Baghdad To America Online

Authors: Lt. Col. USMC (ret.) Jay Kopelman

I'm including some of the forms and studies that I cite in the book.

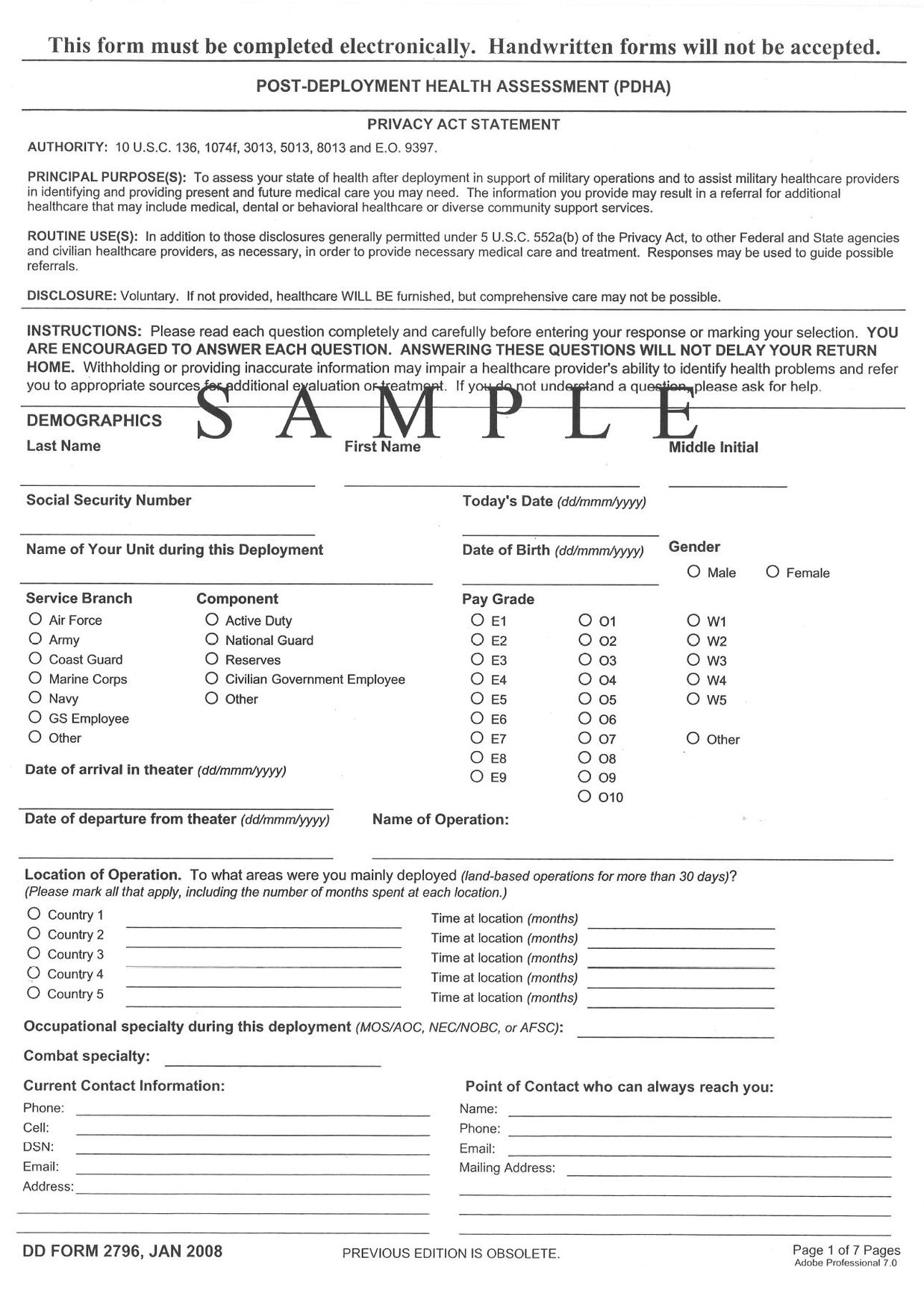

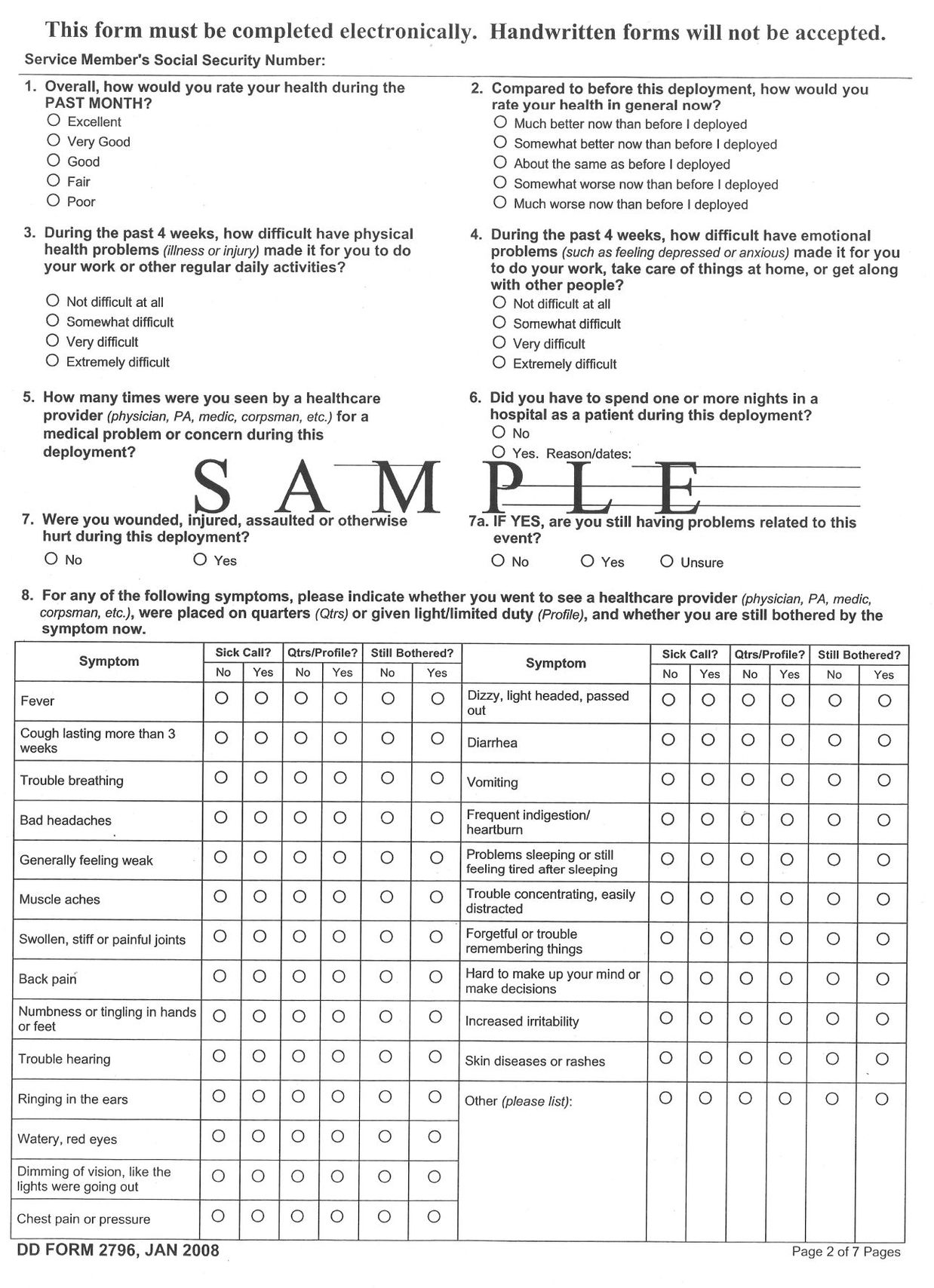

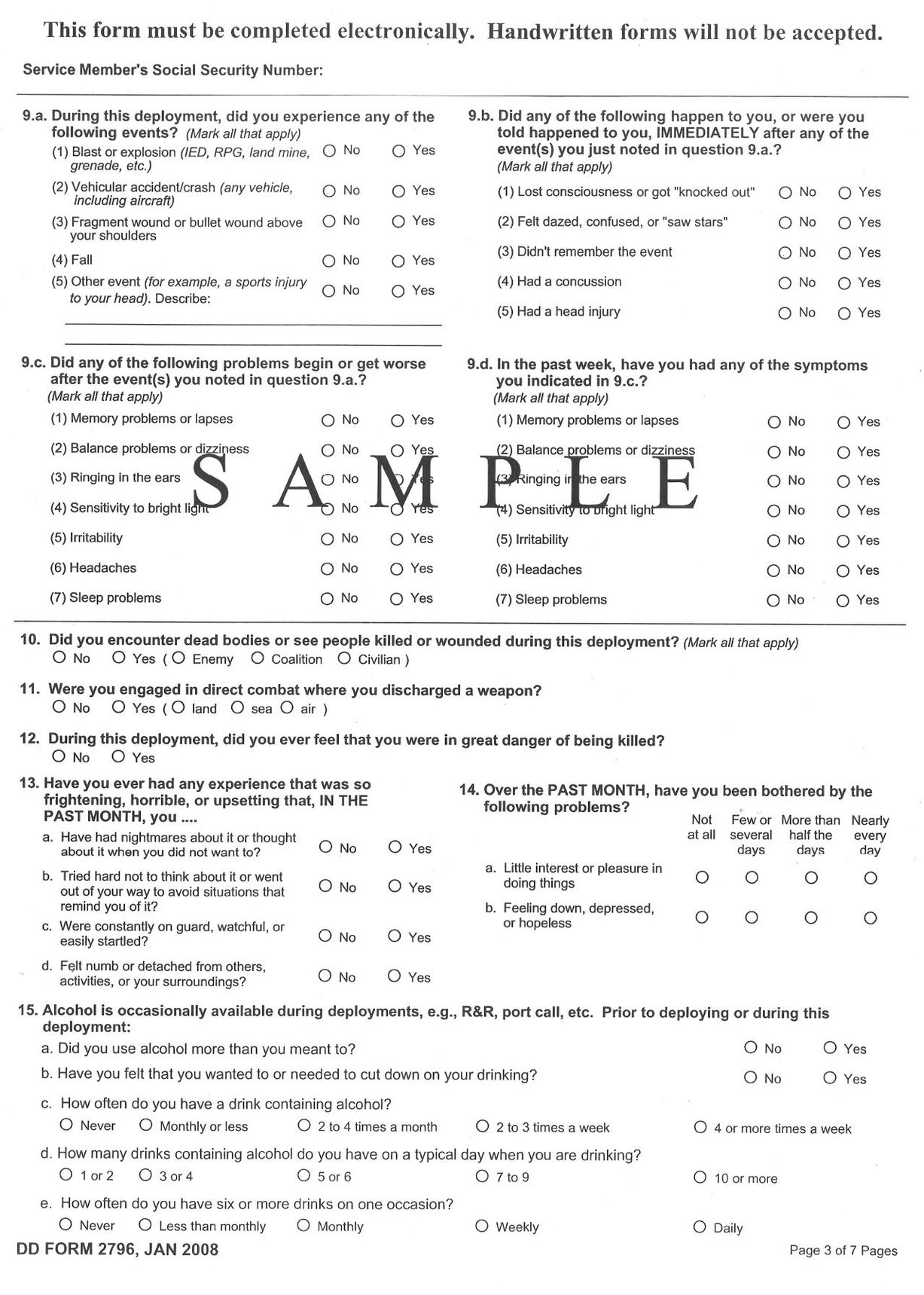

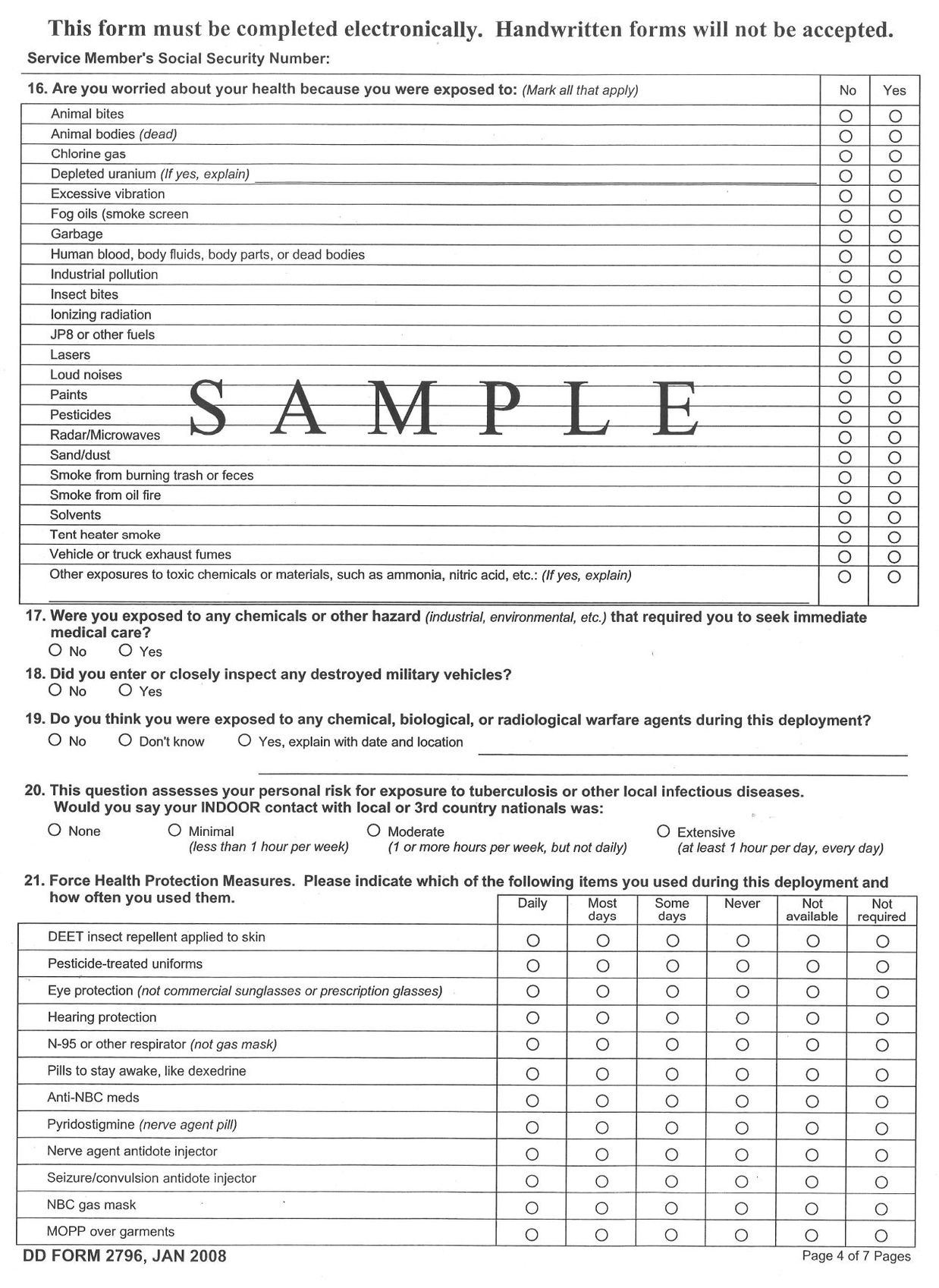

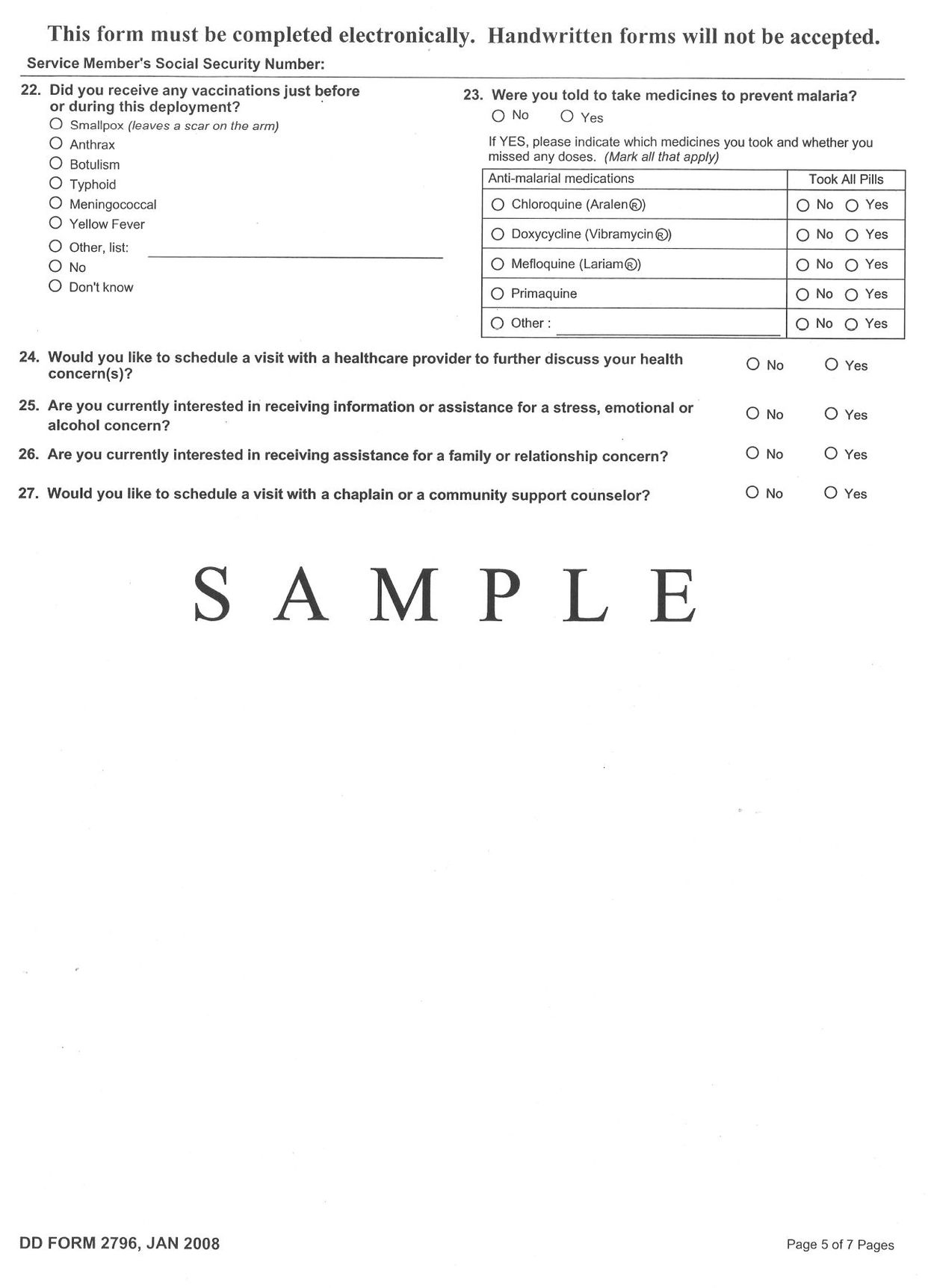

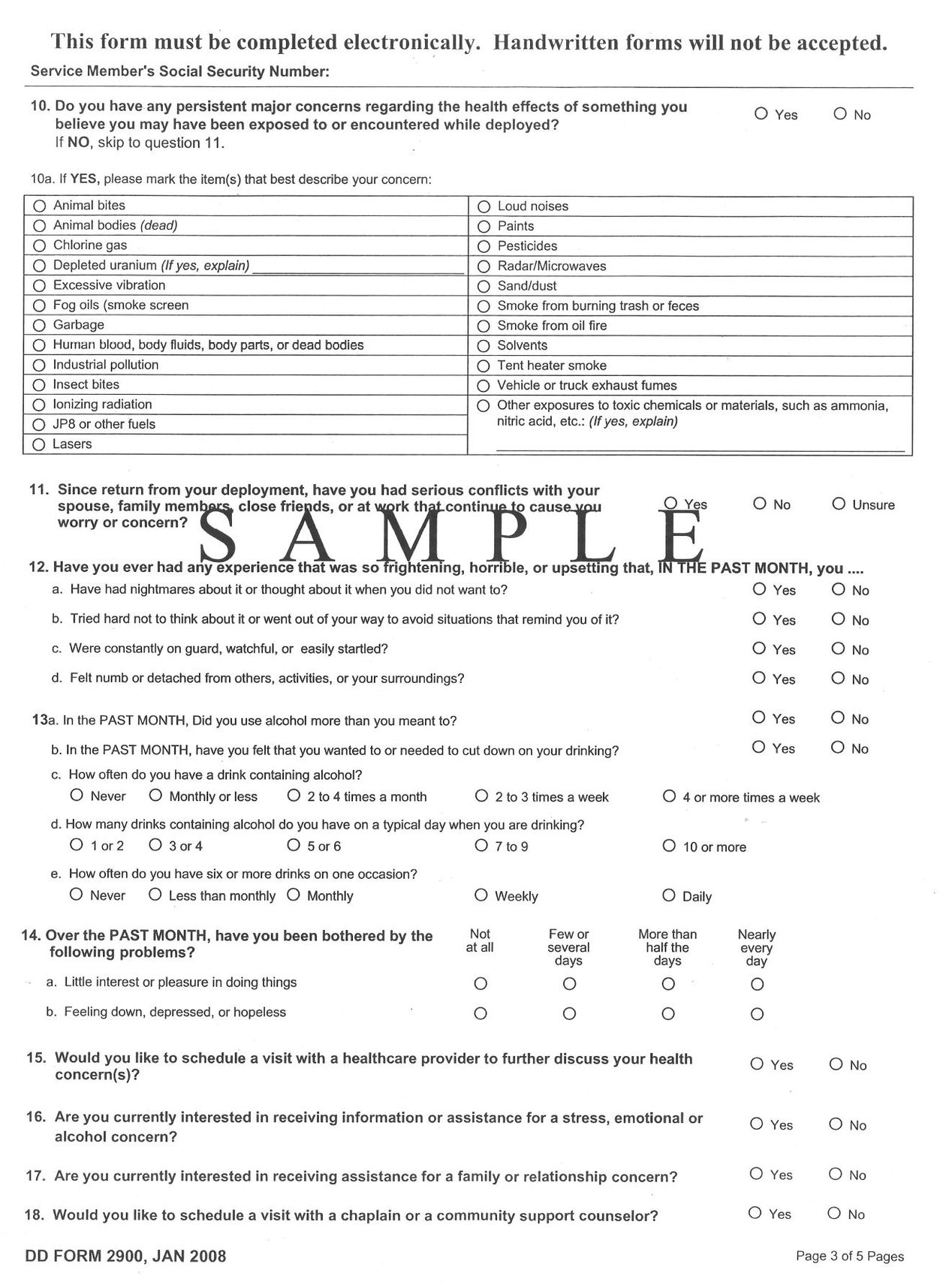

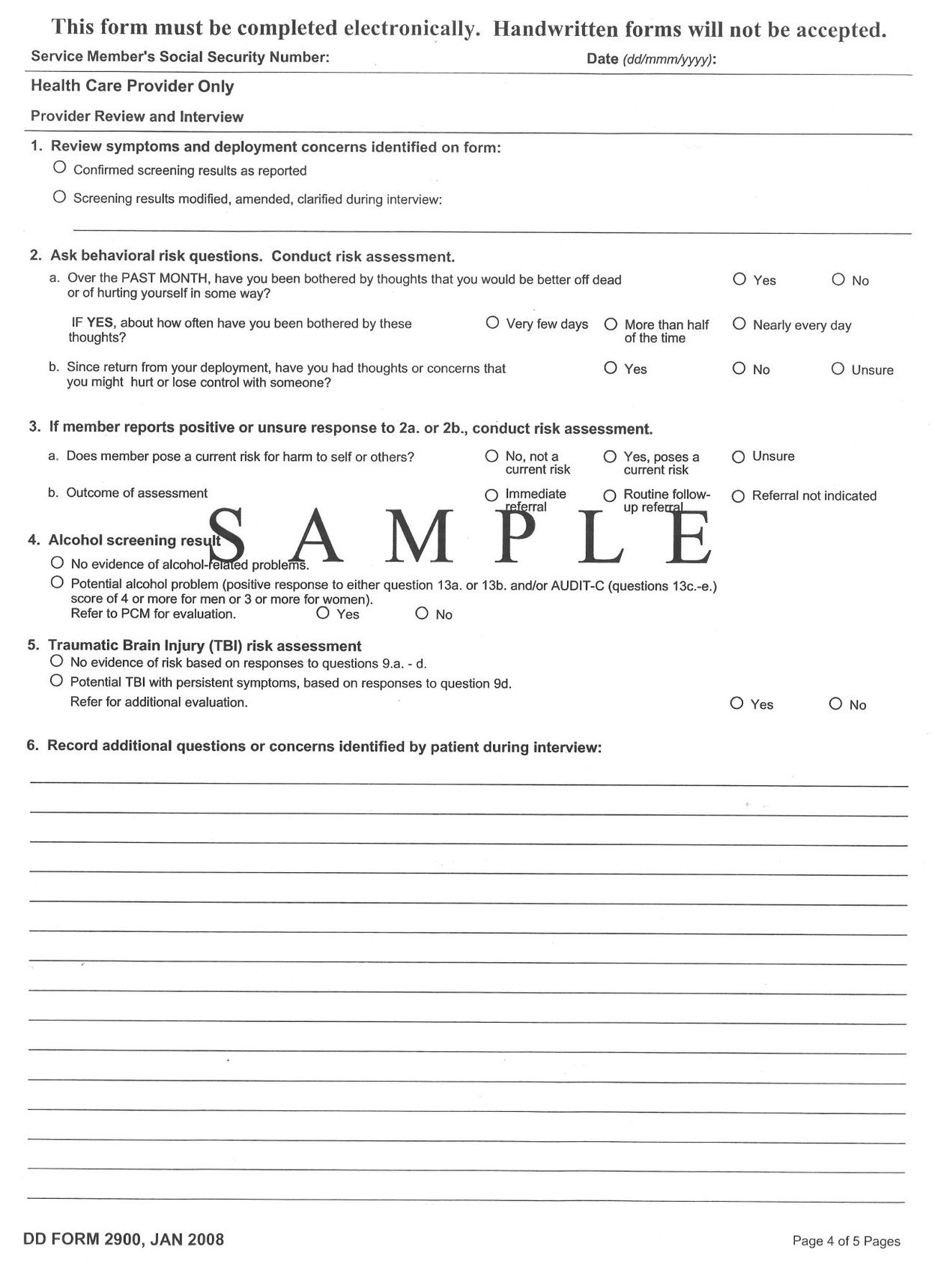

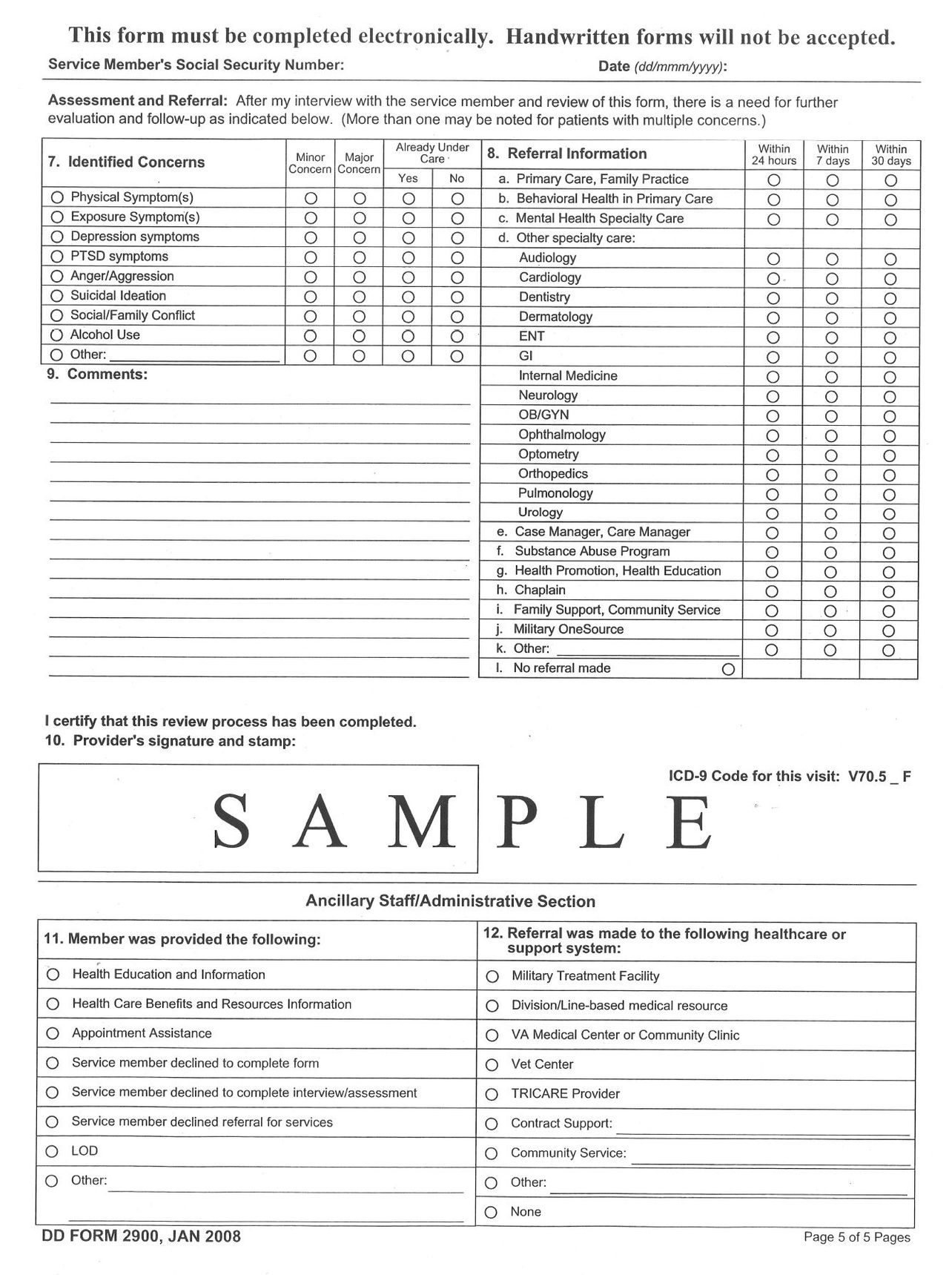

- Post-Deployment Health Assessment (PDHA)

The form soldiers are asked to complete on returning from active duty.

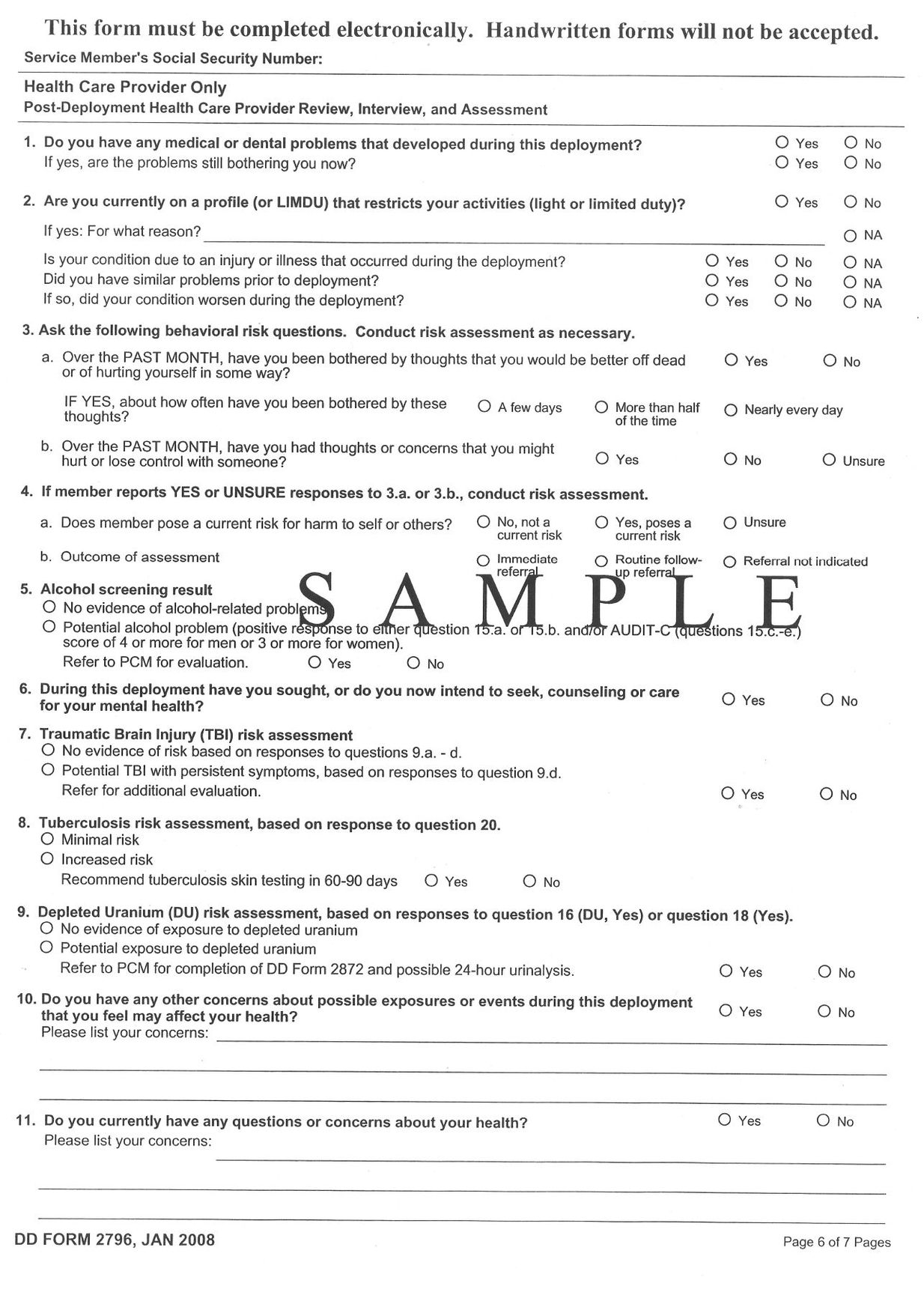

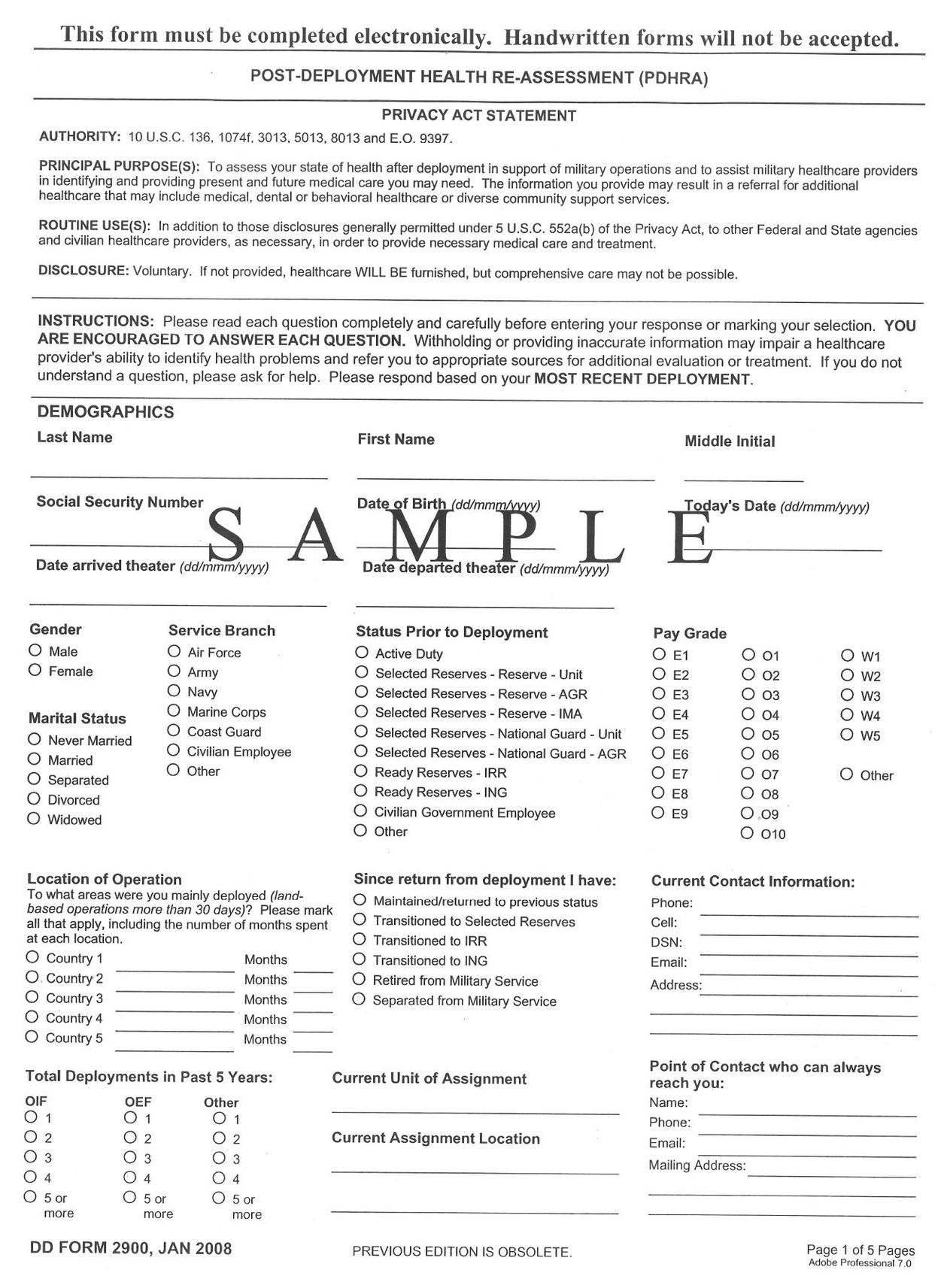

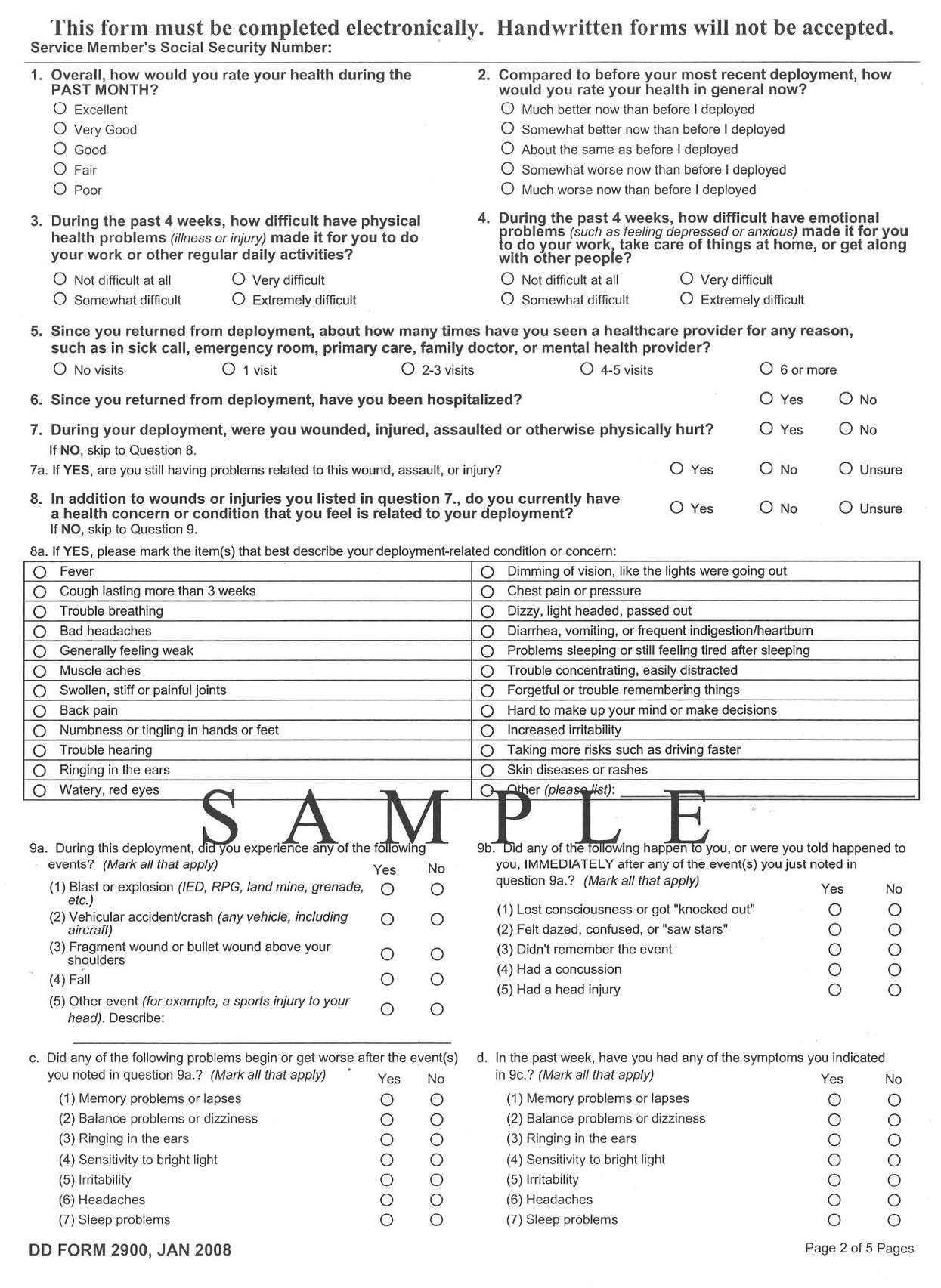

- Post-Deployment Health Re-Assessments (PDHRA)

The form soldiers are asked to complete three to six months after returning from active duty.

- “Mental Health Needs of Soldiers Increase Several Months

After Returning from Iraq War”

A press release describing findings in the 2007 study

published in the

Journal of the

American Medical Association

. - “An Achievable Vision”

A summary of the highly-cited Pentagon Report on mental health and the Armed Forces.

- “Combat Duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, Mental Health

Problems, and Barriers to Care”

The seminal report on the mental health of members of the

Army and Marine Corps involved in combat operations in

Iraq and Afghanistan, published in 2004.

CHICAGOâCompared to initial screening upon returning from the Iraq war, U.S. soldiers report increased mental health concerns and needs several months after their return for problems such as post-traumatic stress disorder and depression, according to a study in the November 14 issue of

The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA)

.

“Our previous article described the Department of Defense's (DoD) screening efforts to identify mental health concerns among soldiers and Marines as they return from Iraq and Afghanistan using the Post-Deployment Health Assessment (PDHA). However, the article also raised concerns that mental health problems might be missed because of the early timing of this screening. It cited preliminary data showing that soldiers were more likely to indicate mental health distress several months after return than upon their immediate return. Based on these preliminary data, the DoD initiated a second screening similar to the first, to occur 3 to 6 months after return from deployment,” the authors write.

Charles S. Milliken, M.D., of Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, Silver Spring, Md., and colleagues analyzed the mental health responses of the first cohort of soldiers (n = 88,235) to complete both the initial screening and the new later screening, with a median (midpoint) of six months between the two assessments. Both screenings included a self-report questionnaire and a brief interview with a clinician.

The researchers found that soldiers reported more mental health concerns, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depression or alcohol misuse during the later screening. Of the 88,235 soldiers, 3,925 (4.4 percent) were referred for mental health care during the initial screening and 10,288 (11.7 percent) were referred during the later screening. Combined data from both screenings showed that the clinicians identified 20.3 percent of active and 42.4 percent of reserve soldiers as needing referral or already being under care for mental health problems.

Among active component soldiers, use of mental health services increased substantially following the later screening, especially within 30 days of the assessment. The majority of all soldiers who accessed mental health care (74 percent, n = 9,074) had not been identified as needing referral.

Concerns about interpersonal conflict increased four-fold between the two screenings. Soldiers frequently reported alcohol concerns, yet very few were referred to alcohol treatment. Although soldiers were much more likely to report PTSD symptoms on the later screening instrument, 49 percent to 59 percent of those who had PTSD symptoms identified on the initial screen improved by the time they took the later screen, suggesting that the increase was due to new symptoms being reported.

“The study shows that the rates that we previously reported based on surveys taken immediately on return from deployment substantially underestimate the mental health burden,” the authors write. “This emphasizes the enormous opportunity for a better-resourced DoD mental health system to intervene early before soldiers leave active duty.

“Increased relationship problems underscore shortcomings in services for family members. Reserve component soldiers who had returned to civilian status were referred at higher rates on the [later screening], which could reflect their concerns about their ongoing health coverage. Lack of confidentiality may deter soldiers with alcohol problems from accessing treatment. In the context of an overburdened system of care, the effectiveness of population mental health screening was difficult to ascertain.”

Editor's Note:

Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, financial disclosures, funding and support, etc.

An Achievable Vision:

Report of the

Department of Defense

Task Force on Mental Health

June 2007

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Section 723 of the National Defense Authorization Act for fiscal year 2006 directed the Secretary of Defense to “establish within the Department of Defense a task force to examine matters relating to mental health and the Armed Forces” and produce “a report containing an assessment of, and recommendations for improving, the efficacy of mental health services provided to members of the Armed Forces by the Department of Defense.” Towards that end, the Department of Defense Task Force on Mental Health (Task Force) was established, comprising seven military and seven civilian professionals with mental health expertise. Task Force members were appointed in May 2006, with one military and one civilian member serving as co-chairs for the group. Lieutenant General Kevin C. Kiley, the Surgeon General of the Army, served as the military co-chair from the inception of the Task Force to March 2007. Vice Admiral Donald C. Arthur, the Surgeon General of the Navy, served as the military co-chair from April 2007 to June 2007. Dr. Shelley MacDermid, director of the Military Family Research Institute at Purdue University, served as the elected civilian co-chair for the duration of the Task Force, from May 2006 to June 2007.

The Task Force acknowledges the good-faith efforts currently being implemented by the Department of Defense and the military Services. In the history of warfare, no other nation or its leadership has invested such an intensive or sophisticated effort across all echelons to support the psychological health of its military service members and families as the Department of Defense has invested during the Global War on Terrorism. These laudable efforts acknowledged, the actual success of the overall effort must be evaluated as a function of the effectiveness of resource allocation and the design, execution, and refinement of strategies.

The costs of military service are substantial. Many costs are readily apparent; others are less apparent but no less important. Among the most pervasive and potentially disabling consequences of these costs is the threat to the psychological health of our nation's fighting forces, their families, and their survivors. Our involvement in the Global War on Terrorism has created unforeseen demands not only on individual military service members and their families, but also on the Department of Defense itself, which must expand its capabilities to support the psychological health of its service members and their families.

The system of care for psychological health that has evolved over recent decades is insufficient to meet the needs of today's forces and their beneficiaries, and will not be sufficient to meet their needs in the future.

In particular, the system is being challenged by emergence of two “signature injuries” from the current conflictâ post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury. These two injuries often coincide, requiring integrated and interdisciplinary treatment methods. New demands have exposed shortfalls in a health care system that in previous decades had been oriented away from a wartime focus. Staffing levels were poorly matched to the high operational tempo even prior to the current conflict, and the system has become even more strained by the increased deployment of active duty providers with mental health expertise. As such, the system of care for psychological health that has evolved over recent decades is insufficient to meet the needs of today's forces and their beneficiaries, and will not be sufficient to meet their needs in the future.

Changes in the military mental health system and military medicine more generally, have mirrored trends in the landscape of American healthcare toward acute, short-term treatment models that may not provide optimal management of psychological disorders that tend to be more chronic in nature. As in the civilian sector, military mental health practices tend to emphasize identification and treatment of specific disorders over preventing and treating illness, enhancing coping, and maximizing resilience. Emerging lessons from recent deployments have raised questions about the adequacy of this orientation, not only for treating psychological disorders, but also for achieving the goal of a healthy and resilient force.

The challenges are enormous and the consequences of non-performance are significant. Data from the Post-Deployment Health Re-Assessment, which is administered to service members 90 to 120 days after returning from deployment, indicate that 38 percent of Soldiers and 31 percent of Marines report psychological symptoms. Among members of the National Guard, the figure rises to 49 percent (U.S. Air Force, 2007; U.S. Army, 2007; U.S. Navy, 2007). Further, psychological concerns are significantly higher among those with repeated deployments, a rapidly growing cohort. Psychological concerns among family members of deployed and returning Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom veterans, while yet to be fully quantified, are also an issue of concern. Hundreds of thousands of children have experienced the deployment of a parent.

Maintaining the psychological health, enhancing the resilience, and ensuring the recovery of service members and their families are essential to maintaining a ready and fully capable military force. Towards that end, the Task Force's vision for a transformed military system requires the fulfillment of four interconnected goals:

- A culture of support for psychological health, wherein all service members and leaders will be educated to understand that psychological health is essential to overall health and performance, will be fostered. Early and non-stigmatizing psychological health assessments and referrals to services will be routine and expected.

- Service members and their families will be psychologically prepared to carry out their missions. Service members and their families will receive a full continuum of excellent care in both peacetime and wartime, particularly when service members have been injured or wounded in the course of duty.

- Sufficient and appropriate resources will be allocated to prevention, early intervention, and treatment in both the Direct Care and TRICARE Network systems, and will be distributed according to need.

- At all levels, visible and empowered leaders will advocate, monitor, plan, coordinate and integrate prevention, early intervention, and treatment.

Together, these interconnected and interdependent objectives define an achievable future. Until each goal is fulfilled, service members and their families will be inadequately served.

In general, the Task Force found that current efforts fall significantly short of achieving each of the goals enumerated above. This assessment was based on a review of available research and survey data, additional data sought specifically by the Task Force, public testimony from experts and advocates, and site visits to 38 military installations throughout the world, including the largest deployment platforms, where thousands of service members, their family members, commanders, mental health professionals, and community partners were given the opportunity to provide their input.

The Task Force arrived at a single finding underpinning all others: The Military Health System lacks the fiscal resources and the fully-trained personnel to fulfill its mission to support psychological health in peacetime or fulfill the enhanced requirements imposed during times of conflict. The mission of caring for psychological health has fundamentally changed and the current system must be restructured to reflect these changes. This requires acknowledgement of new fiscal and personnel requirements necessary to meet current and future demands for a full spectrum of services including: resilience-building, assessment, prevention, early intervention, and provision of an

Actionable recommendations to address the shortfalls outlined above are presented and discussed in the body of this document. These recommendations are designed to address the needs of members of the Active and Reserve Components, their eligible beneficiaries, and other Department of Defense beneficiaries. The Task Force's recommendations are categorized and summarized briefly below:

- Buiding a culture

of support

for psychological health- Dispel stigma

- Make mental health professionals easily accessible

- Embed psychological health training throughout military life

- Revise military policies to reflect current knowledge about psychological health

- Make psychological assessment procedures an effective, efficient, and normal part of military life

- Dispel stigma

- Ensuring a full

continuum

of excellent

care for

service

members and their

families- Make prevention, early intervention, and treatment universally available

- Maintain continuity of care across transitions

- Ensure high-quality care

- Provide family members with access to excellent care

- Make prevention, early intervention, and treatment universally available

- Providing sufficient resources and allocating them according to requirements

- Provide adequate resources for mental health services

- Allocate staff according to need

- Ensure an adequate supply of military providers

- Ensure TRICARE networks fulfill beneficiaries' mental health needs

- Provide adequate resources for mental health services

- Empowering leadership

- Establish visible leadership and advocacy for psychological health

- Formalize collaboration at the installation, Service and Department of Defense levels to coordinate care for the psychological health of military service members

- Establish visible leadership and advocacy for psychological health