Gallipoli (75 page)

Authors: Peter FitzSimons

One more time, the Australian soldiers are cut to pieces, including Trooper Harold Rush and his cobber, shot dead within yards of their trench. If God has blessed either of them, it is not obvious.

In the later, famed words of Charles Bean, âWith that regiment went the flower of the youth of Western Australia, sons of the old pioneering families, youngsters â in some cases two or three from the same home â¦

âMen known and popular, the best loved leaders in sport and work in the West ⦠rushed straight to their death.'

79

Ric Throssell is one of many who goes down within the first few yards, shot through the chest, but still able to call out, âI'm done â but keep on! Keep on! Keep the ball rolling!'

80

And yet rare pockets of men from the third line, including those around Hugo Throssell, actually do make it over the first few yards â¦

As there are so few of them, the situation is clearly hopeless, and with another rare burst of sanity amid all the madness, Hugo Throssell shouts, âGet down!' to the surviving chargers near him,

81

and is immediately obeyed as men hurl themselves to the earth. Miraculously, Throssell has done it at a point where a tiny bit of cover is afforded by a small hollow, which they throw themselves into, lying as flat as they possibly can as bullets whistle overhead. The luckiest ones â and they include Sid Ferrier â are able to get a little added shelter if they have come to ground behind a dead body, and those bodies continue to shake violently as bullets keep pouring in from Turkish gunners.

Still with spirit, Throssell calls out cheerily to those with him, above the ongoing roar of the machine-guns, âA bob in, and the winner shouts!'

82

Is he serious?

He's serious!

Well, there's nothing better to do. And so, just as they had done with their beloved drinking game, the soldiers around Throssell â even as the bullets buzz overhead and the shrapnel bursts â start to âtake a number' and try to âsell a pony'.

But, as later recounted by Sergeant âBig Mac' Macmillan, from Gippsland, âI was just beginning to count when a shell came a bit too near. So we got the word to retire, and never knew on whom those drinks were.'

83

It is a rare moment of levity, and a successful retreat from the carnage, as still out in no-man's-land scenes of agony continue all around.

Over on the left of the assault, Corporal Maitland Hoops hears a ragged voice calling him. It is his close mate, Geoff Howell, bleeding badly and in agony.

âShoot me, please,' he begs Maitland. âI am done.'

84

Maitland cannot bring himself to do it, but, in any case, it is not long before a bullet hits Howell in the head, and he is mercifully no more.

Beside himself with both fury and misery, as the fourth line start steeling themselves to get ready to go over the top, Lieutenant-Colonel Brazier knows he must try once more to stop the charge â and it is all the more urgent when two notes come. One is from Major Tom Todd, the 45-year-old New Zealand-born accountant who has miraculously survived the third charge, and even been able to get this message through, written on the back of a scrap of pink paper, reporting the hideous situation he and the scattering of other survivors have found themselves in, and asking for further orders.

And the second message comes from Major Joe Scott, who is in charge of the fourth line from the far right flank, seeking confirmation of âall the other reports and asking the advisability of pushing on'.

85

Brazier goes looking for the only man who can call it off, now that Antill won't â âas he had never left his trench'

86

â and that is the newly promoted Brigadier-General Frederic Hughes.

He finds Hughes in the bombing emplacement. Saluting, Brazier reports the gravity of the situation, that the first three waves have been massacred for no advance, and that Brigade-Major Antill has ordered them to âPush on'. But he cannot hold himself in, imploring, in stark terms, for Hughes to call off the attack.

The truth of it, Sir, is that âthe whole thing is nothing but bloody murder'.

87

In response, the General utters just four words: âTry Bully Beef Sap.'

88

Brazier is astounded. The General is referring to a trench off to the right that is likely the only trench within coo-ee that is more suicidal to attack than the Nek.

Can he be

serious?

Desperately, Brazier tries to point out the insanity of such a move, but is at least relieved that Hughes is relenting on continuing the hopeless attack at the Nek. Brazier trudges back towards his men, entirely intent on doing nothing. At least the fourth line has been saved.

Meanwhile, the men of the fourth line, caught by the force of a military machine that seems to have no off button, move forward to take their place on the firing step, ready to go up and over. On the right flank, Major Joe Scott is waiting anxiously to find out what Colonel Brazier has achieved and in the meantime â because of the continuing roar of both guns and artillery â has instituted a system whereby the signal for his men to charge will be a wave of the hand, not a whistle.

The soldiers at this point are on a hair-trigger. Their heads are down, and many of them are praying, summoning their last reserves of courage. Their concentration is not on Major Scott but on the man beside them, and on their troop leaders. In that situation, it only needs one man to be confused, to charge, to pull that hair-trigger and the men beside him on both sides will also charge, starting a chain reaction.

And then it happens.

Lost in the fog of war, an officer who knows of Antill's second instruction to âPush on!' but does not know of Brazier's attempt to get General Hughes to call it off arrives at 5.15 am on the right of the line and asks why they have not GONE OVER THE TOP?!?!

89

It is the way he says it.

Captain Andrew Rowan, a grazier from Western Australia, takes it as an order, and immediately waves his arm, before hopping the bags himself, to be shot in the head and fall back dead. But his final wave to the world is seen by Sergeant William Sanderson, who waves himself and also charges forward.

90

In an instant, half of the fourth wave is up and charging!

The chain reaction has exploded.

âBy God I believe the right has gone on!' Major Scott cries,

91

before shouting at the other men to stop. It is too late for most.

The Turkish guns chatter. The Australian men fall.

And die.

The âbutcher's bill', when it finally becomes confirmed â at the moment, many are just âmissing' â is devastating. No fewer than 600 men had hopped the bags, of whom 234 had been killed and 138 wounded.

92

And the Turks, who were meant to be wiped out by the attack? Well protected in their trenches, superbly armed and with more ammunition than they know what to do with, they have lost just a dozen men or so.

And there is no flag in their trenches. The sacrifice of so many men has achieved precisely ⦠nothing.

Brazier returns to the centre of the line, only to hear that ⦠most of the fourth line has gone! Their commander holds out little hope that any of them have survived. As Brazier later recalled, â[I] thought that only myself and my messengers were left.'

93

When an officer of Royal Engineers, whose job today it is to blow up enemy trenches and tunnels, arrives to ask for further instructions â as they have received orders to keep the attack going â Brazier has a firm answer for him. Exhaustedly, no longer caring if he is court-martialled, but simply unwilling to waste another life uselessly, Colonel Brazier tells the officer that they are NOT to proceed, and he will answer for it personally.

Nigh speechless with fury and grief at the entirely needless slaughter of his men for absolutely no gain, Colonel Brazier can do nothing for now but wait and observe, âa lonely sentinel watching with a periscope'.

94

After half an hour, he sends a written message to Brigade HQ, notifying them âthat the trenches are empty, that if attacked the Turks can run right over the British troops and will H.Q. send up reinforcement and relief'.

95

When the reply comes back, Brazier grabs the note with his dirt-encrusted hands and reads, âKeep on observing.'

96

But let Charles Bean have a final word: âAnd as for the boys â the single-minded, loyal Australian country lads â who left their trenches in the grey light of that morning with all their simple treasures on their backs to bivouac in the scrub that evening â the shades of evening found them lying in the scrub with God's wide sky above them â¦'

97

BATTLE FOR THE HEIGHTS

My candle is all but burnt out â¦

1

Colonel William Malone, Commander Wellington Infantry Battalion, writing to his wife before marching out to Chunuk Bair

All men, all creatures, suffer from tiredness. But men have a mental force which allows them to go on without resting.

2

Mustafa Kemal, Anafarta Group Commander,

DAWN, 7 AUGUST 1915, ABOVE SUVLA BAY, THE TRUTH DAWNS

He is a man with crystal-clear blue eyes, high cheekbones and an air of great authority about him. He is Colonel Mustafa Kemal, standing atop Battleship Hill, gazing through his binoculars at the tumult below. And he is in no doubt that his prediction has become a reality. The invaders are trying to go from âAnzac in the direction of Hill 971, just as predicted all along'.

3

(He had

told

them so.)

At least Kannengiesser's 9th Division has been despatched towards the heights, which brings him some relief.

The sun is rising as Malone and his men, as well as the other New Zealanders on hand, set about securing the ridgeline at the Apex, concealed just below Rhododendron Ridge, with Chunuk Bair just beyond on high. Malone presumes this is the spot from where they are to launch their final assault on the summit, but he cannot be sure as Johnston, along with the officers of the Brigade headquarters, has still not arrived to the head of their column, so he now sends word back to the Commander:

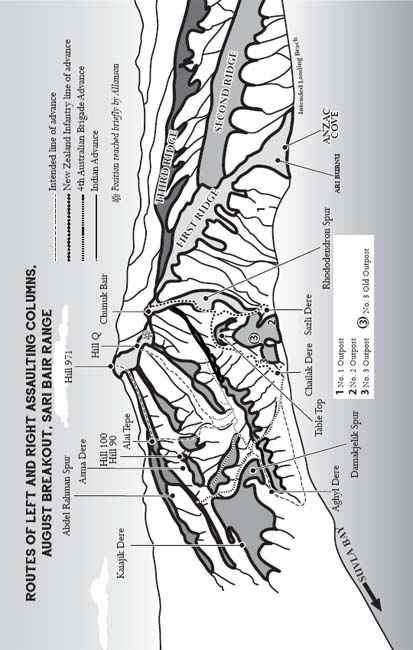

August Offensive â Breakout, by Jane Macaulay

7th August

OC N.Z. Inf Bde

I am occupying a position nearly at the head of the gully. As it is day and I am not sure of my position, I am lining the crest of the surrounding ridges to ensure reasonable safety.

I am reconnoitring forward and will act on further knowledge and report.

W. G. Malone

Lt. Col

4

A short time later, Johnston and his staff join them at the ridge. Johnston appears particularly dishevelled and inarticulate, brimming with fighting spirit â or some kind of spirit, for the smell of strong alcohol is apparent â yet somehow morose.

Though half of their men are dispersed and not ready for an attack, Johnston insists in his own impulsive way that the attack go ahead as per their instructions. The heights must be seized, regardless of delay.

But Malone, a man of âinflexible resolution'

5

and convinced it will be an exercise in suicide, will not hear of it. Certainly not yet, when they know nothing of what lies before them.

As the New Zealanders vacillate, the relatively undefended heights above them are beginning to be reinforced.

Kannengiesser and his gaggle of senior officers, after riding hard from Kemalyeri, are forced to dismount for the final scramble up the steep, scree-strewn slope to the narrow, razor-edged plateau at Chunuk Bair. With the help of prickly bushes and rough grass, they pull themselves atop the comb's edge at around 6.30 am. Catching his breath, Kannengiesser looks through his binoculars across the rugged hills and out to the Aegean Sea, where the most amazing thing emerges from the rising mists â¦

Suvla Bay is full of ships! They count âten transports, six warships, and seven hospital ships'.

6

The warships are firing on Turkish positions on land, while the transports are disgorging ever more soldiers onto a shore that is already crowded with them.

âOn land,' the German officer would later recount, âwe saw a confused mass of troops like a disturbed ant-heap, and across the blinding white surface of the dried salt sea we saw a battery marching in a southerly direction. With our few revolvers we could do nothing against it.'

7

Returning his gaze to the slopes in front of him, he sees that it is just a confusion of valleys â obviously difficult country to traverse if the enemy is coming their way â but on the other hand he can see no Turkish defensive positions from this particular vantage point. In fact, the prevailing sense all around him is a certain âpeace and quiet'.

8

Now concerned by the immensity of the ridge that he has been charged to defend, he begins âa reconnaissance of the country so as to be able to receive the approaching regiments with final orders'.

9

In terms of existing defences, all he can find just down from the summit is one battery â whose commander is fast asleep â manned by 20 sleepy gunners.

Kannengiesser does not like it at all. The English are making for the heights of Sari Bair Range, and if they capture them the battle will be lost. And he has too few troops for the length of front he has to defend.

Immediately this moustachioed 47-year-old military professional â regarded by Colonel Kemal, a hard marker, as âone of the most talented of all the German officers in our army'

10

â begins to dictate reports to his second-in-command. This worthy hurriedly translates them into Turkish for the benefit of the troops, while another Turkish officer keeps a lookout with his inevitable binoculars. (Like doctors with stethoscopes, Turkish officers must always have binoculars around their necks. And if they want to achieve the highest of ranks, a luxurious moustache is a near must.)

Tucked just behind the lip of Rhododendron Ridge, unseen by Kannengiesser, the New Zealand troops are, for the moment, safe. And yet Malone's instinct to keep his men right there until they are better supported on their flanks and have more situational understanding is now being overturned. For, once more, Johnston insists the men go forward and advance on the summit of Chunuk Bair, come what may.

So be it. The exhausted, thirsty and hungry men of the New Zealand Infantry Brigade begin a slow, single-file march forward. Onwards and upwards, ever upwards.

With the first rays of the sun now hitting the peaks, the Turkish officer with his binoculars is still standing atop Chunuk Bair, making a slow, sweeping scan, from left to right, of the rugged ground below.

Suddenly, he gives a start and jerks the binoculars back to a point he'd just passed over, trying to focus on something.

There!

From out of the dusky dimness just 500 yards below, struggling towards the light, he sees

Ingiliz

soldiers exhaustedly climbing, âsplendidly equipped with white bands on their left arms'.

11

And though they appear tired, this string of soldiers emerging from the valley below seems to never end.

Still

they keep coming.

The instant that the attention of Colonel Kannengiesser is drawn to it, the German officer immediately orders the nearest Turkish soldiers â the 20 that he'd found defending the Turkish battery â to open fire, but they refuse.

âWe can only commence to fire,' the response comes, âwhen we receive an order from

our

battalion commander.'

12

Kannengiesser explodes. He runs over and jumps among them, and in a mixture of outraged German, what little Turkish he knows and international sign language for âI will shoot you myself if you don't do as I say', manages to achieve the desired result.

The Turkish soldiers start firing down on the climbing soldiers below, and the exhausted New Zealanders immediately throw themselves to the ground like freshly scythed wheat. âThey gave me the impression,' the German Colonel would later say of the New Zealand soldiers, âthat they were glad to be spared further climbing.'

13

Monash, meanwhile, is completely exhausted, as are his men, after the most frustrating night of their lives. In the darkness, trying to follow the impossible route, being fired upon by tireless pockets of Turks, they have failed to reach their objective of Hill 971, and for the moment can go little further.

For now, Monash orders his men to dig in on this eastâwest ridge, which, according to the rudimentary map he carries, seems to put them in good position to eventually launch an attack on their objective. (He is mistaken. They are in fact still 600 yards short of where he believes they have reached. But still the men work on, entrenching their positions in the wrong place.)

It's now approaching 8 am, and two companies of Colonel Kemal's 19th Infantry Division arrive just in time to help to defend Chunuk Bair. Kannengiesser now has some 250 soldiers. The New Zealanders have hunkered down, many retreating to the Apex as the two sides engage in a light skirmish, trying to determine the other's strength.