Geeks (14 page)

I tried to explain the circumstances, the sudden move from Idaho. “Jesse has been in an office tower since October,” I added, as I prepared to leave. “He’s seen something of the world. He understands what a college education means, what the alternatives are. Somebody needs to take a chance on this kid. If he doesn’t make the move now, he might head off in a different direction.”

O’Neill nodded noncommitally and walked me out of the building and two blocks to the nearest cab stand. If I were in Chicago again, I should drop by; he’d love to have me sit in on his Enlightenment class. Our conversation had been interesting, helpful.

Like Jesse after he’s been forced to talk too long, I was spent. O’Neill had been gracious and attentive, but there was no reason to believe Jesse was an inch closer to getting into school.

In Lakeview, Jesse was waiting for me—though he was, of course, online. I understood his particular style of greeting, by now: He’d buzz me into the Cave, leaving the door ajar. When I walked in, he’d be sitting at his computer with his back to me. He’d yell hi, then clack away for a few minutes, while I took out my notebook and strolled through the place, playing writer and cataloguing the apartment’s meager contents. I’d ask if he was hungry. Sure, he’d say, and he’d log off whatever program he was on, throw on a jacket, leave the computer running, and walk out with me.

This time the apartment was exactly as I’d last seen it, except the Katz Diet Coke can was gone, consumed by the forlorn friend from Idaho.

We went to a Japanese restaurant, and I filled Jesse in on the not-so-positive news.

The dean, I said, had been polite, but he didn’t seem to quite know who Jesse was. “I guess the fact that he didn’t throw me out of his office is a good sign,” I said lamely. “I mean, if there were no chance whatsoever, he would have probably told me.” I told Jesse that O’Neill would be expecting his call, that the next move was his. But frankly, I said, I wouldn’t get my hopes up.

Three weeks later, Jesse met with Dean O’Neill. I called that night to see how it went.

“Reasonably well,” he said. “Ted’s a cool guy.” Ted?

They’d gotten into an extended argument about free will, Jesse said, which was cool. Jesus, I thought, Jesse took on a University of Chicago dean over free will? What kind of argument?

“Well, he was completely wrong,” Jesse said. “We argued about whether or not there exists a faculty of reason unique to man. Whether man is the only beast capable of true reasoning. I argued that no, there is no such thing as reason, just chemistry and electricity . . . the mind is just a mass of chemicals and electricity. There’s nothing magic about it. There’s absolutely no spiritual consciousness that allows us to be more deeply reasoning than other creatures in the world.”

O’Neill, Jesse said, was teaching his Enlightenment course that day, so the subject had been on his mind. He disagreed, as Jesse recounted it, but then conceded that he really “couldn’t argue with my science.”

Was that what they talked about? Mostly, said Jesse. He’d talked about his life and school record, and the Dean had asked if he’d finished high school at all. He seemed relieved that he had. Otherwise, they’d spent most of an hour in their free will battle, which Jesse said was “awesome.”

The geeks versus the Enlightenment. I bet O’Neill had poured himself a stiff drink at lunch afterward.

What did he say at the end? I asked.

“He said he didn’t know whether I could be admitted or not, but that he’d love to have me in his humanities class.”

GEEK VOICES July 1997 Hello Jon, You could say the majority of Americans were always geeks, until we got post-Depression urbanization and illusions of sophistication. We looked like Dorothy’s Kansas friends in —Jeff |

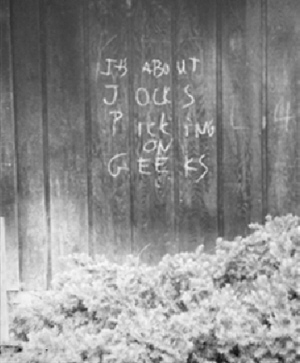

Photo taken in Kalamazoo, Michigan, shortly after the Columbine shootings.

SIMON KING

10

INTO THE HELLMOUTH

From:

Jesse Dailey

To:

Jon Katz

Exactly prior to the Geek Club era, I went through my rebellious phase and got pretty heavy into drugs and got involved in a gang. . . . It was that whole seeking-out thing that eventually landed me in the Geek Club. . . .

A guy in Nampa (who was a loose friend of ours) walked into the front door of our mutual enemies and shot him and his brother point blank in the face, killed A and vegetabled his brother; 3 of us put 4 bullet holes in the back of a van that was speeding away from us. Things during that time were pretty fucked up, I was big into amphetamines and acid, and I couldn’t think very straight at all. . . .

I would say that that was one of the most important changes that technology made, was that it helped me to wake up out of that, during all this I was still big into computers at home, and I was always the guy who fucked with all the stolen computer shit, and when I started being involved in the Geek Club, I kinda started seeing how shitty of an existence that would have been.

> > >

FOR THE

alienated, brainy, oddball young souls of the world, there was life before the Internet and life after. Had he been born twenty years earlier, Jesse would have probably suffered the traditional geeks’ fate in school, then slunk home to read comics and watch some bad TV. If he were lucky, Eric would have watched with him.

But life for geeks has been transformed. For one thing, they aren’t alone anymore. They probably still loathe school, but when they go home, their computers are passports to a vast, complex, and communicative world, one still largely invisible to many parents, educators, and other adults.

High priests in journalism and culture are fond of fussing that the Internet is dislocating, isolating, dangerous. After spending so much time online, talking to so many kids like Jesse and Eric, I view it differently. It isn’t the Net that drives kids into isolation or creates lonely children; the Net attracts lonely and ignored kids, and puts them in touch with others just like them.

Jesse has spent more time in this world than in any other for much of his life—since the fifth grade, he guesses. It has shaped him as much or more than any other cultural, social, or educational force, or combination thereof.

When the

Idaho Statesman

ran its feature on Internet-obsessed kids in 1995, with Jesse as the Net-addict poster boy, he told the reporter he spent thirty-five to forty hours a week on the Net. “His favorite spot is the inter-relay chat site, where he talks with friends for five to six hours a night during the week, usually until 3

A.M.

on Saturday and noon to 10

P.M.

on Sunday,” the paper noted. If anything, Jesse spends more time online now; the things that draw him there—games, weblogs, chat and messaging systems, open source operating programs—have become far more advanced and compelling.

Such kids don’t suffer alone anymore. They tell their stories to one another almost continuously, via twenty-four-hour, seven-day-a-week messaging systems much more advanced than the IRC in the

Statesman

’s story. Programs like ICQ and Hotline make it simple to set up communities of like-minded people with shared interests. These programs open windows on a computer screen that stay open day and night.

For geeks, these are the real news media. Jesse spends much of his time on Hotline, talking to friends all over the country and around the world about music, software, sometimes actual news. Such friends are invisible, but they exist.

The rest of the time, these kids go to school, do homework, and sleep in their beds every night. But in their hearts and souls, they dwell in the geek nation. And ignorance of that alternative world is dangerous, sometimes putting both its citizens and society at peril.

At lunch on the day of my Chicago visit, Jesse and I could hardly stop talking about what had happened at Littleton. There was much more to say about it than about my inconclusive session with Dean O’Neill. Somehow, Jesse had escaped that degree of anger and disconnection. But he’d brushed against it, come close. There but for the grace of God . . .

He’d never kill anybody, Jesse said firmly. But he had to admit he felt some sympathy for the two young killers, if none for their brutal actions. He’d walked a way in those shoes, he said.

Now he could see what was coming. “You wait, they’ll blame the geeks,” he predicted, meaning the general “they” of the media and its alleged experts. “They’ll blame computer games and the Net. Life for geeks like me who are still in high school will be hell. . . . It probably already is.”

I ran for my plane, telling Jesse I’d call him that night. After our discussion, I thought I should write something about this, maybe for Slashdot, the techno-centered website that was among geeks’ favorite gathering spots. I was also thinking that, as cooler observers around me had been cautioning, it would probably be saner, cheaper, and easier for Jesse to try for the University of Illinois in the fall. He was preparing for that shift in strategy. At lunch, we’d agreed to go on the U of I’s website that week to look at the courses and application process.

By that evening, when I called Jesse, the news from and about Columbine was already confirming his predictions. “Computer games: How they may be turning your kids into killers!” was the promo on one New York newscast. The cable channels were filling with moral guardians, politicians, pundits, and therapists warning about computer games like Doom (which the Columbine killers played) and about hate material on the Net (the killings took place on Adolf Hitler’s birthday). We heard warnings about black clothes and white makeup, Goth music, computer addictions. We learned various warning signals of youthful disconnection and disturbances. “They” were describing geeks.

Net hysteria, a staple of modern journalistic and political life, flares up whenever there’s a killing, sex assault, new virus, hacking incident, or other problem even remotely connected to the Internet.

These hysterias are well known to anybody who spends any time online, though the incidents are extraordinarily rare when viewed in proportion to total Net and Web use. But every geek has had a brush with a parent, a teacher, a clergyman, someone who’s branded his or her Net passion dangerous, unhealthy, addictive, or bizarre. When Jesse and a few friends started playing computer games in the Middleton High library at lunchtime, nervous parents forced the librarian to make them stop.

None of this was awfully far in his past and, as we talked about Columbine, the anger bubbled up, still fresh. He’d spent a few hours on media and geek sites that evening, gauging the reaction to the Littleton kids who’d been dubbed the Trenchcoat Mafia.

The horror stories were already pouring in, Jesse reported: kids sent home for wearing trench coats or black clothing, ordered into counseling for playing games like Quake and Doom.

“If I were in high school,” Jesse sputtered, “I would show up in a trench coat and fedora. I’d wear them every single day. I would make them suspend me, by God. I would fight them every step of the way, the arrogant sons of bitches.”

After a while, he calmed down. “You never want to hurt anybody,” he explained. “But there were a lot of days when I was at Middleton that I’m glad I didn’t have a gun around. It’s a piece-meal, gradual, daily grinding down of you as a human. First, there’s the school, where you have to leave the Constitution and all your rights at the door. They tell you what to think, where to sit, what to wear. They tell you what you can and can’t read. They try to tell you what to think.

“The whole school is set up for other people—jocks and preppies, sports. You are not valued at all. You are constantly taunted, humiliated, elbowed, laughed at. The classes are boring and most of the teachers don’t care if you live or die. People hate you for having ideas, for talking about them, for being different. You are never—ever—invited to anything. High school is like a whole universe of parties, groups, activities to which you are the only person who doesn’t have the key, who never gets an invitation.

“You start to get angry, then you start to hate. They just slice away your humanity, piece by piece, and the hate becomes bigger and bigger, until there’s nothing left but hate. If you don’t have good friends or a teacher or a parent to talk to, then one day, there’s just no humanity left. You’re

all

hate. You have no connection to the world. And so you snap.” This anger is always near the surface in Jesse, even now.

What had rescued Jesse was the camaraderie of the Geek Club, one sympathetic teacher, a sense of mastery from his computing skills, and the ability to talk with his sister and mother.

But the parallels to Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, the suicidal gunmen, were frightening and eerie.

The New York Times

subsequently reported that the two had performed well in class, but remained far on the outskirts of the social scene. And there was this: “Expert computer programmers who configured games like Doom to their own specifications, the two were once suspended for hacking into the school mainframe. But the boys also helped maintain Columbine’s Linux server, and taught classmates how to download from the Internet.” That could as easily have been written about Jesse or Eric.

By now, extensive talks with them and with hundreds of geeks online had given me some insight into the alienation rampant in geek culture. So I wrote the first in a series of Slashdot columns we called the “Hellmouth” series.

Slashdot is a center for the open source and free software movements. Nearly ten years ago, Linus Torvalds, then a student in Finland, developed a computer operating system called Linux, which was collectively improved by geeks all over the world and distributed free to anyone who wanted it. The only restrictions were that improvements had to be shared at no cost. The open source movement has grown to more than eight million users, perhaps the geekiest social movement on the Net, since its members and passionate adherents are programmers and designers. They would understand something about alienated youth.

“The Hellmouth,” the entry point for evil in the world, is a term recently popularized by the geek-beloved TV series

Buffy the Vampire Slayer

; its witty central conceit is high school as Hellmouth, entryway into this world for vampires, ghouls, and predators.

The following is an abridged version of the first column to run after the Columbine massacre. It brought an avalanche of e-mail, the first of which came from Jesse: “Brav-fucking-O. you really hit the nail on the head with this one!”

FROM THE HELLMOUTH

THE BIG

story never seemed to quite make it to the front pages or the TV talk shows. It wasn’t whether the Net is a place for hatemongers and bomb-makers, or whether video games are turning your kids into killers. It was the spotlight the Littleton, Colorado, killings has put on the fact that for so many individualistic, intelligent, and vulnerable kids, high school is a Hellmouth of exclusion, cruelty, loneliness, inverted values, and rage.

From

Buffy the Vampire Slayer

to Todd Solondz’s

Welcome to

the Dollhouse,

and a string of comically bitter teen movies from Hollywood, pop culture has been trying to get this message out for years. For many kids-often the best and brightest-school is a nightmare.

People who are different are reviled as geeks, nerds, dorks. The lucky ones are excluded, the unfortunates are harassed, humiliated, sometimes assaulted literally as well as socially. Odd values—sunthinking school spirit, proms, jockhood—are exalted, while the best values—free thinking, nonconformity, curiosity—are ridiculed. Maybe the one positive legacy the Trenchcoat Mafia left was to ensure that this message got heard by a society that seems desperate not to hear it.

I’ve gotten a steady stream of e-mail from middle- and highschool kids all over the country, kids in trouble or who see themselves that way to one degree or another in the hysteria sweeping the country after the shootings in Colorado.

Many of these kids felt like targets of a new hunt for oddballs—suspects in a bizarre, systematic search for the strange and the alienated. Suddenly, in this tyranny of the normal, to be different wasn’t just to feel unhappy, it was to be dangerous.