George's Cosmic Treasure Hunt (23 page)

Read George's Cosmic Treasure Hunt Online

Authors: Lucy Hawking

“Why has Cosmos sent us here?” asked George.

“Once you and Annie had realized the clue led to one of the moons, Cosmos calculated that Titan was the most probable location for life of some kind to have existed, due to the chemical composition of its structure and atmosphere. Cosmos thinks you will find the next clue on Titan,” Emmett told them. “Although I have to admit, he doesn't seem to know where. He's being a bit of a buzzkill at the moment. Sometimes he's really helpful and then suddenly he starts sulking.”

“Dude. Chill out,” complained Cosmos.

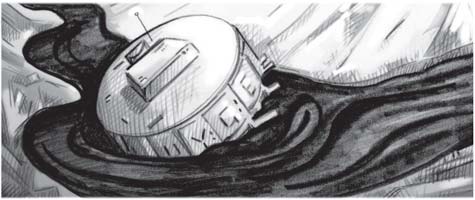

“Ooh, look!” said Annie, pointing toward the lake. “What is it?” Drifting on the tide toward them, they saw a shape like a lifebuoy or a boat.

“It looks like a machine,” said George. “Like something that came from Earth.”

“Unless,” said Annie, “there's someone here and it belongs to themâ¦Emmett,” she went on slowly, “is there anyone out here? And if there is, do we want to meet them?”

“Um,” said Emmett, “I'm trying to check on Cosmos, to see what he's got on his files for life on Titan.”

“No,” snapped Cosmos. “I'm tired now. Go away.”

“He's starting to run low on memory,” said Emmett. “And we're going to need him to open up the portal to get you back fairly soon. So I'm looking in

The User's Guide

instead. Here we areââIs There Anyone Out There?' This should tell us.”

THE USER'S GUIDE TO THE UNIVERSE

IS THERE ANYONE OUT THERE?

Will some readers of this book walk on Mars? I hope so. Indeed, I think it is very likely that they will. It will be a dangerous adventure and perhaps the most exciting exploration of all time. In earlier centuries, pioneer explorers discovered new continents, went to the jungles of Africa and South America, reached the North and South Poles, and scaled the summits of the highest mountains. Those who travel to Mars will go in the same spirit of adventure.

It would be wonderful to traverse the mountains, canyons, and craters of Mars, or perhaps even to fly over them in a balloon. But nobody would go to Mars for a comfortable life. It will be harder to live there than at the top of Mt. Everest or at the South Pole.

But the greatest hope of these pioneers would be to find something on Mars that was alive.

Here on Earth, there are literally millions of species of lifeâslime, molds, mushrooms, trees, frogs, monkeys, and, of course, humans. Life survives in the most remote corners of our planetâin dark caves where sunlight has been blocked for thousands of years, on arid desert rocks, around hot springs where the water is at boiling point, deep underground, and high in the atmosphere.

Our Earth teems with an extraordinary range of life-forms. But there are constraints on size and shape. Big animals have fat legs but still can't jump like insects. The largest animals float in water. Far greater variety could exist on other planets. For instance, if gravity were weaker, animals could be larger and creatures our size could have legs as thin as insects'.

Everywhere you find life on Earth, you find

water.

There is water on Mars and life of some kind could have emerged there. The red planet is much colder than the Earth, and has a thinner atmosphere. Nobody expects green goggle-eyed Martians like those that feature in so many cartoons. If any advanced intelligent aliens existed on Mars, we would already know about themâand they might even have visited us by now!

Mercury and Venus are closer to the Sun than the Earth is. Both are very much hotter. Earth is the Goldilocks planetânot too hot and not too cold. If the Earth were too hot, even the most tenacious life would fry. Mars is a bit too cold but not absolutely frigid. The outer planets are colder still.

What about Jupiter, the biggest planet in our solar system? If life had evolved on this huge planet, where the force of gravity is far stronger than on Earth, it could be very strange indeed. For instance, there could be huge balloonlike creatures floating in the dense atmosphere.

Jupiter has four large moons that could, perhaps, harbor life. One of these, Europa, is covered in thick ice. Underneath that there lies an ocean. Perhaps there are creatures swimming in this ocean? To search for them, there are plans to send a robot in a submarine.

But the biggest moon in the Solar System is Titan, one of Saturn's many moons. Scientists have already landed a probe on Titan's surface, revealing rivers, lakes, and

rocks. But the temperature is about minus 274 degrees Fahrenheit (170 degrees Celsius), at which any water is frozen solid. It is not water but liquid methane that flows in these rivers and lakesânot a good place for life.

Let's now widen our gaze beyond our Solar System to other stars. There are tens of billions of these suns in our Galaxy. Even the nearest of these is so far away that, at the speed of a present-day rocket, it would take millions of years to reach it. Equally, if clever aliens existed on a planet orbiting another star, it would be difficult for them to visit us. It would be far easier to send a radio or laser signal than to traverse the mind-boggling distances of interstellar space.

If there was a signal returned, it might come from aliens very different from us. Indeed, it could come from machines whose creators have long ago been usurped or become extinct. And, of course, there may be aliens who exist and have big “brains” but are so different from us that we wouldn't recognize them or be able to communicate with them. Some may not want to reveal that they exist (even if they are actually watching us!). There may be some superintelligent dolphins, happily thinking profound thoughts deep under some alien ocean, doing nothing to reveal their presence. Still other “brains” could actually be swarms of insects, acting together like a single intelligent being. There may be a lot more out there than we could ever detect. Absence of evidence isn't evidence of absence.

There are billions of planets in our Galaxy and our Galaxy itself is only one of billions. Most people

would guess that the cosmos is teeming with lifeâbut that would be no more than a guess. We still know too little about how life beganâand how it evolvesâto be able to say whether simple life is common. We know even less about how likely it would be for simple life to evolve in the way it did here on Earth. My bet (for what it is worth) is that simple life is, indeed, very common but that intelligent life is much rarer.

There may not be any intelligent life out there at all. Earth's intricate biosphere could be unique. Perhaps we really are alone. If that's true, it's a disappointment for those who are looking for alien signalsâor who even hope that some day aliens may visit us. But the failure of searches shouldn't depress us. It is perhaps a reason to be cheerful because we can then be less modest about our place in the great scheme of things. Our Earth could be the most interesting place in the cosmos.

If life

is

unique to the Earth, it could be seen as just a cosmic sideshowâthough it doesn't have to be. That is because evolution isn't over. Indeed, it could be closer to its beginning than its end. Our Solar System is barely middle-agedâit will be six billion years before the Sun swells up, engulfs the inner planets, and vaporizes any life that still remains on Earth. Far-future life and intelligence could be as different from us as we are from a bug. Life could spread from Earth through the entire Galaxy, evolving into a teeming complexity far beyond what we can even imagine. If so, our tiny planetâthis pale-blue dot floating in spaceâcould be the most important place in the entire cosmos.

Â

Martin

“Is there anyone out there?” said Emmett. “I think probably notâat least, not where you are. So far, I think it's just you and the lakes of methane.”

“Ugh! It's raining!” said Annie. She held out one hand to catch a raindrop. Huge drops of liquid, three times the size of raindrops on Earth, were falling from the sky. But they didn't fall fast and straight, like normal rain. They dawdled in the atmosphere, wafting and twirling around like snowflakes.

“Oh no!” said Emmett. “It must be methane rain! I don't know how much pure methane your space suits can withstand before they start to deteriorate.”