Georgian London: Into the Streets (33 page)

Read Georgian London: Into the Streets Online

Authors: Lucy Inglis

The MCC was formerly the White Conduit Club (which played at White Conduit Fields in Islington). The WCC was a club for gentlemen, including ‘J. Wyatt’, who was very likely the busy young architect. The gentlemen, however, did not like to lose. By 1785, the club was employing professional players, including Edward ‘Lumpy’ Stevens, John ‘Little Joey’ Ring, as well as a bowler, one Thomas Lord. Lord was an enterprising man; when they grew out of White Conduit Fields, he was asked to find a new ground. In 1787, Lord took a lease on a piece of ground in Dorset Fields, and the MCC was born. There is no evidence the ground was ever called anything but Lord’s. In 1806, it hosted the first Gentlemen vs Players match. In 1810, a row over the lease caused them to move again. Three years later, in 1813, the development of the Regent’s Canal threatened Lord’s once more, and the wily bowler shifted the ground to its current site. By this time, cricket was part of the London summer scene. Surrey and Hampshire Ladies played at Ball’s Pond in 1811, and 1827 saw the first Oxford vs Cambridge match at Lord’s.

The mixture of artisans, gentlemen and aristocrats in the early lists of players at Lord’s is typical of Marylebone. Successful artisans and artists, in particular, were quick to move into the comfortable and elegant, yet not too grand, housing offered by the area.

The area’s artistic community would fill a book, so numerous are the names. They include Edward Gibbon, the historian, whose epic work

The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

was published in 1787 to great acclaim, and was unsurpassed until the twentieth century.

Others included the artist Henry Fuseli, who lived in Berners Street, and also the Rose family of plasterers, who lived in Queen Anne Street East. The workshop of Robert Adam’s ‘ingenious’ Mr Rose was responsible for most of the fine plasterwork within the homes Adam built. The Ward family of builders was busy in Berkeley Square for generations. They were so well regarded that their odd-job man and plumber were dispatched by carriage to customers at country houses in the home counties.

Marylebone artists included J. M. W. Turner, John Opie, George Stubbs (whose house is now buried beneath the north-west corner of Selfridges), John Constable and Sir Edwin Landseer. One of the most prominent names of the time was Richard Cosway. After a fairly meagre start, in Tiverton, Devon, he arrived in London, aged twelve, where he became the pupil of William Shipley, drawing master on the Strand. Shipley had founded the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (now the Royal Society of Arts), which offered prizes on the presentation of ‘

the Best Drawings

, by Boys and Girls, under the age of 14 years, and Proof of their abilities, on or before the 15th day of January, 1755’.

The young Cosway went on to win all the drawing prizes there, and came second only to Joseph Nollekens for the sculpture prize. Key to establishing Cosway’s popularity was his ability to paint beautiful portrait miniatures with a trademark ‘blue sky’ background. They functioned as photographs, painted on ivory so that the skin tone was always perfect, no matter what ravages smallpox, acne and age had left behind. Shipley’s Society of Arts organized a landmark exhibition of living British artists. Previously, the fashion had been for dead continental artists, but the exhibition – comprising 130 works by 69 artists – was seen by 20,000 visitors in a fortnight. It turned the tide for London’s artistic community. People started buying modern art.

Cosway prospered. He moved from Marylebone to Pall Mall before returning to Stratford Place, where he established a beautiful household of great taste and style. This grace was not matched by his person, for ‘

Cosway, though a well-made little man

, was certainly very much like a monkey in his face’. He suffered many ‘monkey’ pranks in his time, but played up to it, even owning a baboon as a pet

until it bit him, wounding him quite seriously. His friend John Townley reported that:

…

the last time I called

I found him laid on a sofa in his night gown and the calf of one of his legs bundled up; on my enquiring the cause he acquainted me, that his monkey or Baboon had tore a great Piece out of his leg and that he was under Dr Hunter’s hand of a cure; the Poor animal has been put out of its pain, by the same hand, and the Dr had the pleasure of Dissecting him, and put him in spirits, in terrors to all Monkeys.

Cosway wasn’t only an artist but also a dealer and broker often ‘

at the Elder Christie

’s Picture-Sales, full-dressed in his sword and bag; with a small three-cornered hat on the top of his powdered toupee, and a mulberry silk coat, profusely embroidered with scarlet strawberries’. The cartoonists mocked him in his vanity – ‘Poor Tiny Cosmetic!’ – though they did allow him to be far better than the ‘indifferent daubers’ of the day.

In his late thirties, he decided to marry. Maria Hadfield was born in Italy, the daughter of a gentleman who had ‘

kept [a Florence hotel]

these twenty and eight years and where most of the English Nobility and Gentry have lodg’d … It is and always has been a house in very great Esteem.’ His convent-educated daughter Maria was the only survivor of a serial killer. Her parents had sent out four or five of her elder siblings to a wet nurse, but all died. Suspicious, they decided to keep Maria at home. A short time later, a nanny found the wet nurse in Maria’s bedroom, inside the Hadfields’ home, and alerted the household, whereupon the wet nurse said she was only ‘sending them to Heaven’. This extraordinary and tragic event caused the family to convert to Roman Catholicism, a faith Maria clung to and used as an increasingly large crutch during the rest of her life.

Maria was an artist of some note in her own right. Richard did not allow his talented wife to paint for money, and so her career was limited, though she did exhibit occasionally. Along with Anne Damer and Mary Moser, Maria Cosway was one of the foremost women exhibiting in London in the 1780s. She and Richard held

artistic salons for London artists and intellectuals. They ‘

kept a house in style

, in a sort of co-partnership of so novel a character, as to surprise their new neighbours, astonish their old friends, and furnish wonderment for the table-talk of the town’. William Hazlitt said, ‘

they were not fashionable

- they were fashion itself’. They employed a black servant, Quobna Ottobah Cugano, known to them as ‘John Stewart’.

He was part of

the Sons of Africa group and campaigned against slavery, using his and the Cosways’ address when he wrote to those he hoped to win over to the cause.

Richard and Maria had one child, Louisa. Maria loved to travel to the Continent, and probably had an affair with a smitten Thomas Jefferson in Paris, during 1786. She returned there, ostensibly to make drawn catalogues of the pictures in the Louvre, just after Louisa was born. In reality, the Cosway marriage was in crisis and Maria was probably suffering from post-natal depression. By the time she returned to London, almost six years later, Louisa was dead and Richard heartbroken.

Richard struggled with his mental health after Louisa died. The extant sketch of her, dead and peaceful, is deeply affecting. He had her body embalmed and kept it in the hall of their house in a marble sarcophagus. His collection of drawings, particularly his important old masters, became less and less important to him. Thomas Lawrence, himself responsible for the greatest collection of drawings by old masters ever to have existed in Britain, thought Cosway’s collection more important. The 1820 catalogue of the Cosways’ Stratford Place home included: 27 Correggios, 67 Michelangelos, 44 Raphaels (school of), 39 Titians, 92 Rubens, 46 van Dycks and 30 Rembrandts. They were dispersed in 1822, after Cosway’s death; of the 2,500 sold, less than 10 per cent have been traced.

Richard Cosway died suddenly

in a carriage on the way to a friend’s house at the same moment as, unbeknownst to him, Maria had the body of their daughter interred and the sarcophagus sent to Joseph Nollekens for safekeeping.

Regent’s Park is now Marylebone’s premier green space, but during the eighteenth century the park had yet to be created and was a wild, open space. Instead, Londoners preferred the safe and enclosed space of Marylebone Pleasure Gardens. The gardens were on a smaller, more intimate scale than Vauxhall and Ranelagh, but their contribution to London’s contemporary entertainment scene was significant.

The first prominent mention of the Marylebone Pleasure Gardens is by Samuel Pepys on 7 May 1668, when he went ‘to Marrowbone, and there walked in the garden, the first time I ever was there, and a pretty place it is’. The gardens Samuel visited were on the east side of what is now 35–37 Marylebone High Street. They extended from the back of the Rose of Normandy Tavern, and at the beginning comprised little more than a bowling green and a gaming house with a beautiful, unobstructed view of Highgate and Hampstead.

As the Cavendish Square development grew, the gardens began to provide more high-quality entertainment, such as music, illuminations and fireworks, for which it became famous. It wasn’t all about formal entertainment, and the gardens were open for breakfast between ten and one o’clock. Daniel Gough, the proprietor, set the entrance fee at a shilling for every gentleman, allowing his lady in for free. The gardens had a no smoking rule and a refined atmosphere. Fidget, the young Elizabeth Montagu, and her teenage friends used to swim in the nearby ponds before rolling in for a late breakfast, where they chatted with the other guests.

Swords and pistols were checked at the gate to prevent quarrels getting out of hand, but outside the premises they were necessary. Owing to demobbing and the economic uncertainty of the 1740s, London suffered waves of street crime. The journey to and from the gardens was dangerous, and muggings were common. It even became necessary to have a company of armed guards to escort groups to and from the gardens, and torches burned along the field path down to Marylebone Lane.

In the 1750s, Handel’s favourite tenor, Thomas Lowe, took over

the gardens. He spent a fortune on them, which almost ruined him, but this was probably the high point in the gardens’ history. The quality of the music reached a peak. Thomas Arne, composer of ‘Rule, Britannia!’, had a talented ten-year-old son, Master Michael Arne, who sang through the summer season of 1750, drawing large crowds.

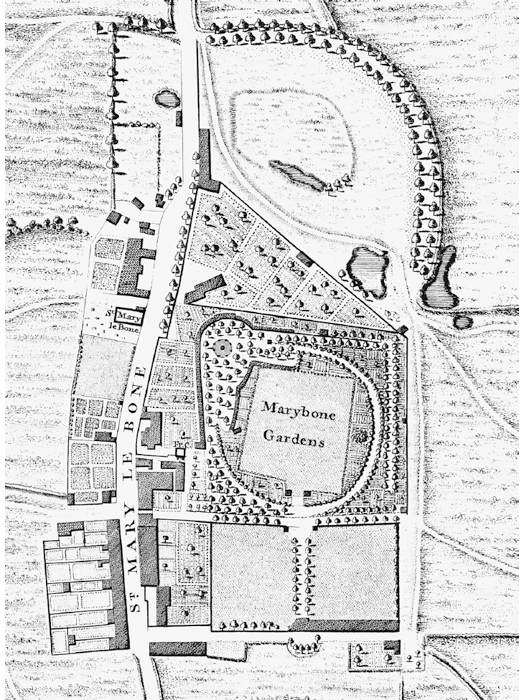

Marylebone Pleasure Gardens, detail from John Rocque’s map, 1745. The buildings on the lower left housed the Harleian Collection, which formed the core of the British Library

By this time, the local school – originally run by Huguenot Denis de la Place – had been taken over by Dr Fountain and his wife. Dickensian ideas of harsh schooling are rather displaced by the images conjured up by one boy who remembered the pupils calling Dr Fountain ‘Bushwig’, owing to his preference for an old-fashioned full-bottomed wig. They also called his wife ‘Rainbow’, because of the frequency with which she dyed her hair varying colours. Rainbow, in particular, was remembered for cajoling the homesick boys to do their homework with sweets and rewards.

Both Rainbow and Bushwig were regulars at the Marylebone Gardens.

Dr Fountain was a friend of Handel

, and one day the two men were walking in the garden, as they often did. The band was playing.

Handel paused at the back, saying, ‘Let us sit down, and listen to this piece, I want your opinion on it.’

They sat, and after a short while, the robust, bushwigged Dr Fountain declared, ‘It’s not worth listening to – it is very poor stuff.’

Handel got to his feet and sighed, ‘You are right. I thought so myself when I had finished it.’

The gardens continued to flourish, specializing in

burletta

, a type of short, comic opera. But by 1757, the end was in sight – although the Truslers, who bought the gardens that year, could not have known. The increasing number of wealthy residents both south and north of Oxford Street were protesting about the filth and noise from the many cattle driven along it to Smithfield. The Turnpike Trusts, local authorities with permission to manage the roads, were gathering clout. A new road was seen as a lucrative speculation, given the weight of traffic. The New Road was London’s first large bypass, running from the end of the Edgware Road to Tottenham Court Road, past St Pancras to St John Street, in Islington. It was created

quickly and bounded by fence posts. Initially, the traffic didn’t bother the pleasure gardens, and things carried on as usual.

The Truslers had three great strengths: the Neapolitan musician Stephen Storace, who married their eldest daughter; their interest in good fireworks; and their second daughter, Miss Trusler, who did the catering. The Truslers’ son-in-law was an able composer and musician. He was often employed by Teresa Cornelys, in Soho Square, and was one of London’s busiest and most admired popular musicians. His own compositions were sold exclusively at the gardens, and the print runs were large. He and his wife, Elizabeth, had two children. Their son, also Stephen, studied music in Vienna and befriended Mozart, but died young at thirty-two. Their daughter, Anna Selina, known to everyone as ‘Nancy’, would be Mozart’s first Susanna in

The Marriage of Figaro

, in 1786.