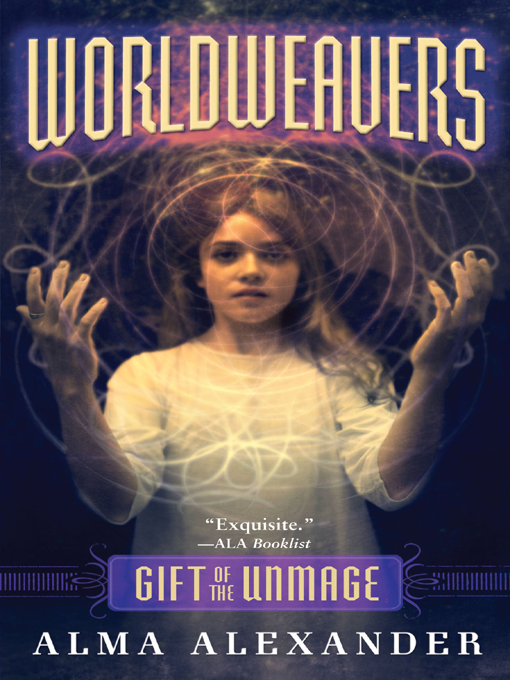

Gift of the Unmage

Read Gift of the Unmage Online

Authors: Alma Alexander

Tags: #Children's Books, #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #Fantasy & Magic, #Literature & Fiction, #Fantasy, #Contemporary, #Children's eBooks, #Science Fiction; Fantasy & Scary Stories, #Paranormal & Urban

Gift of the Unmage

Book 1

The first book for Lea, the eldest

1.

“Y

OU SMELL ANGRY

,” Aunt Zoë said as she walked in through the door, sniffing in Thea’s direction like a hound dog scenting prey.

She was always coming up with things like that. Things like

The wind looks blue

. Or

That song was scratchier than a scouring pad!

Or telling someone that their purple dress was “loud,” and meaning it quite literally. She heard things other people smelled, or saw things other people heard, or absorbed colors through the tips of her fingers.

Although she had been only three at the time, Thea vividly remembered the time that Zoë had said that the wind was blue. It might have been the first real, coherent memory that she could lay claim to. She had piped up with enthusiastic

agreement, and had not failed to notice the immediate excitement her words had caused. What she had failed to understand at the time were the reasons behind that excitement, and had happily mimicked Aunt Zoë’s strange ways on several occasions after that, seeking the approval that she had received the first time she had done it. But it had become all too obvious very quickly that she was merely saying the words, not experiencing them the way that Zoë did. The passing years had made Thea wiser. People had still been expecting great things of her when she was very young—anything she did, anything she said, might have a sign of the Double Seventh latency waking into its full potential. But it always fell flat, usually with someone sighing deeply, “Oh,

Thea

.” She’d been almost six years old before she realized that her full name was not, in fact, both those words.

“I’m just upset,” Thea said to her aunt, kicking the edge of the couch with the heel of her free foot, the one she had not folded comfortably underneath her.

“Have they been at you again?”

Thea made a face. “They’re

always

at me.”

“What is it now?”

Thea gestured at the dining room table in the next room, where two objects rested amid an untidy heap of papers. One of them was a perfectly seamless metallic cube. The other was an irregularly shaped blob that may or may not have been made of the same material, and looked like something angular had tried and failed to hatch from a steel egg.

“What on earth is that?” Zoë said, fascinated.

“Ars Magica class assignment. We were supposed to turn the cube into the ball.”

Zoë tore her eyes from the thing on the table and turned a sympathetic gaze on her niece. “Uhoh. Did

you

do that?”

“You mean the blob? Nope. That was Frankie’s effort. The cube…is mine.”

The frustration and humiliation of an Ars Magica class were nothing new for Thea. The routine hardly ever varied—an assignment would be given, and then, at the end of the class, certain students would be invited to stay behind. Thea was invariably one of them; her brother Frankie, who was a year behind his peer group and known to be a klutz with anything magical, was another. But even Frankie could eventually do some part of the assignment, in however ham-

fisted a way, while Thea could not even manage something that could be classified as a mistake. There would be others, whom Thea bitterly recognized as window dressing, who were there only to show that she was not singled out for anything—as though she could be fooled. The reactions of the others ranged from sympathy (from some who had to work harder at their own talents than the rest) to smoldering resentment for even being forced to sit in the same classroom as the two Winthrop siblings and being tainted by so much as being in their presence. Afterward in the cafeteria, one particularly vicious classmate had complained loudly about being forced to breathe the same air as Dunce and Idiot over there and how their ineptitudes were already eating at his own abilities.

“I can feel it,” he had said in a mock-dolorous voice, his hand raised to his forehead in the manner of old television melodramas. “It’s all fading, it’s all going awaaaaaay…. This time tomorrow I’ll be no more than a dumb ’dim, and my parents will disown me.”

“Ah, I wouldn’t worry,” one of his henchmen said with a sly glance over at the other table where Thea sat by herself, with her hair hanging

over her face to hide her flaming cheeks. “Their parents still love them, wouldn’t you know….”

It only became worse when Thea and Frankie brought their Ars Magica transformations back home that day. Thea had produced hers with a sinking heart, without raising her head to meet her father’s eyes.

“What was it?” Thea’s mother had asked.

“That,” Thea muttered. “It was the cube.”

“What was it supposed to

be

?” asked Anthony, the oldest brother. It was a Friday, he was home from college for the weekend and full of more than his usual smug self-importance.

Thea muttered something under her breath.

“What?” Anthony said.

“Oh,

Thea

,” Frankie said. He produced his own effort, half cube, half shapeless blob. “It was supposed to be…”

“Well, not

that

,” Anthony said with a chuckle.

“A ball,” said Frankie defiantly. “It was supposed to be a ball.”

“You mean like this one?” Anthony had picked up Thea’s untransformed cube and had been turning it over in his fingers; now he passed his other hand over it, murmuring a single word,

and he was suddenly holding a smooth metal sphere that sat on his palm like an accusation.

Thea grabbed for it. “Give it back! That was mine!”

“Oh,” Anthony said, “okay.” He passed his hand over it again before she had a chance to snatch it, and it was back in cube form.

“Anthony,”

Paul murmured, in a halfhearted reproof.

“Show-off,” Thea snarled, still avoiding looking at her father, her fingers curling around her cube as though she wanted to throw it. “When I get to University—”

“You won’t,” Anthony said. “Not at this rate.”

“You wait! When I get to Amford—”

“You can’t go to Amford,” said Frankie. His words fell into the conversation like stones into a pond. Ripples of things that did not need to be said followed them into the silence.

You can’t go to Amford, Thea. Amford is the University of Magic. You can never go to Amford, Thea. You can never…

Not even Paul could gainsay that one.

Thea stared at her hand, willing her fingers to uncurl from around the unforgiving cube. Then

she very carefully put it down on the dining room table and walked away.

She had meant to stalk off into her room and slam the door, but somehow she didn’t have the energy to move any farther than the living room couch, where she sat and stared out of the window until her aunt came into the room.

Now Zoë was staring at the dining room table. “Frankie’s supposed to finally graduate to the advanced class next year,” she said thoughtfully. “They deal with living things there.” She was looking at the mangled thing that Thea had called the blob, and it was clear that she was seeing some poor rat or lizard half-turned into a human ear by Thea’s ham-fisted older brother. “Is he in trouble?”

“Not nearly as much as me,” Thea muttered.

“Oh,

Thea

.”

Thea jumped up from the couch. “Don’t you start! I’ve been hearing that all day. Even Frankie did the oh-Thea thing, and look at what

he

brought home.” She rubbed at her nose with the back of her hand in a faintly reflective manner, as though she was using the gesture to help her think. “Maybe I was adopted.”

“Don’t be silly,” Zoë said, and sniffed again.

“You’re a miserable little thing today, aren’t you? The very air in this room smells brown and shriveled, and it’s all your fault. It’s nice and crisp out—you want to go out for a walk? And tell me the rest of it? You’ll feel much better if you get it off your chest, you know. Maybe I can help.”

“Get what off my chest?” Thea said suspiciously.

“Thea, darling, you are prickly with secrets; I can feel them coming out of you like a porcupine’s quills. You’re upset about something that your parents haven’t told you openly—you’ve been eavesdropping again. I can always tell, you know.”

“I don’t…,” Thea began indignantly, but just then a door closed loudly, and she threw a quick calculating glance that way and then nodded at Zoë with suspicious eagerness. “On second thought, I’d like that. A walk would be good.”

“Just taking Thea out for a wander!” Zoë called out over her shoulder. “Grab your jacket and run,” she whispered into Thea’s ear, as she shepherded her niece out the door. “If they don’t see you, they can’t stop you.”

Zoë was the kind of aunt who was less than

beloved by responsible parents. She was a conspirator with errant children, with a fine disregard for rules and the charm to talk herself back into everyone’s good graces afterward. She was perfectly aware of the crisis brewing in the Winthrop household, centering—once again—upon her fourteen-year-old niece, the child upon whom so many hopes had been hung on the day of her birth that Zoë sometimes wondered how she had managed to grow up at all under the weight of them.

The Double Seventh—the most magical of the magical, the seventh child born of the union of two seventh children.

The newborn Thea had made the newspapers on the day that her mother, Zoë’s older sister Ysabeau, left the hospital. Then, it had all been pure excitement—Zoë remembered the smell of the air on that morning, sharp and bright like electricity, the precious bundle cradled in her sister’s arms. The baby—Galathea Georgiana, as Ysabeau informed the waiting press with the air of having named a crown princess—had resented the hubbub that had greeted her arrival, and the massive concerted flash of the photographers’ cameras had been too much. The front-page

photograph of the Double Seventh child had shown a bundle of dark blue baby blanket with stars on it wrapped around a small, tightly scrunched-up face that, at that moment, seemed to be mostly mouth.

“She has her father’s gums,” her paternal grandfather had commented irritably when the newspaper had found its way to him. “I suppose now that she’s famous she’ll grow up to be a little spoiled brat.”

And for a while it looked like Thea might do just that.

The photograph and the accompanying front-page article had been placed in the Thea Book (all the Winthrop children had a scrapbook devoted to them)—Ysabeau had a fondness for the photo, even if only because she believed that it had been an unusually good likeness of herself. But Thea’s scrapbook, started from the outset with a rush of hope and anticipation in a notebook much thicker than most of the ones devoted to her brothers, had remained disappointingly barren of material. Zoë had once told Ysabeau that she had never seen another single thing that smelled so much of despair.

Thea’s thoughts were still mutinous as she and

Zoë made their way down the street, leaving their dark footprints in the thin layer of snow on the ground. She was not aware that she had been stomping ahead on her own, leaving her aunt behind, until Zoë’s whistle brought her up sharply. She stopped, turned her head, and realized that her aunt was waiting a couple of hundred feet back.

“Over here,” Zoë said. “We’ll take the trail.”

“But you usually can’t get through there after it’s snowed,” Thea said.

“There are always ways,” said Zoë mysteriously.

Thea, her hands jammed into the pockets of her anorak, trudged back to her aunt’s side, her face thunderous. “Aunt Zoë, if you want me to practice any warming spells, you know what comes next. Anthony would give you a perfect spring day. Frankie would make it hot enough to grow bananas or else he’d turn you into a human icicle. Me, I am just going to do a whole lot of concentrating and then nothing will happen. As usual.”

“You

do

have it bad,” Zoë murmured. “Let me do the spells, hon. Just come this way. The road just smells too hard, I need earth beneath my feet.”

They turned off the road, ducking into a

hardly discernible gap between bare-branched bushes that, in the summer, might have been a blackberry thicket. Beyond them the underbrush thinned as taller trees, cedars and Douglas firs, started to tower above the narrow path. There was snow on the ground, but less than Thea had thought there would be. Whether that was due to the heavy evergreens or because Zoë’s warming spells were working, Thea didn’t know, but it was quite pleasant to walk through the woods in the crisp cool January day. Thea fought to hold on to her funk, but the winter air worked its icy fingers into the snarls of her temper, loosening them until all she still carried was a kind of detached bleakness.

Zoë waited until she finally smelled the change of mood in Thea, and then turned her head fractionally to smile down at her niece.

“All right,” she said. “Want to talk about it now?”

“Dad’s eyes,” Thea said.

This was the sort of shortcut verbal telepathy that Zoë could follow with the ease of one linked by blood kinship. She nodded.

“Yeah, I can see that. Was it when the Ars Magica blobs came in?”

“He’s used to Frankie being a ham-fisted idiot,” Thea burst out. “He’s repeating this year of school, after all. When the…

blob

…came in, Daddy just sighed and rolled his eyes. But with me…with me…every time I fail…”

“He keeps believing in you,” Zoë said gently.

“I don’t know,” Thea said. “I’m not sure if it isn’t just that he wants to keep believing in me. And every time I muck something up, it’s like I do it deliberately, just to hurt him. I saw his face when the last reports came in from school. It doesn’t matter that I’m top of the class in math or in two different foreign languages. He turned straight to the Ars Magica report card and, well, you know what it said.”

“No,” said Zoë.

“What it usually says,” Thea said, kicking a stone on the path with the toe of her boot. “That I’ll never amount to anything. That I can’t do the simplest thing that any toddler can do. That any

newborn

can do. I—can’t—do—

anything

!” Thea punctuated the last sentence by sharp little blows of her fists against her legs. “And then, the sphere…”

“Tell me about the sphere.”