Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World (29 page)

Read Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World Online

Authors: Hugh Brewster

Tags: #Ocean Travel, #Shipwreck Victims, #Cruises, #20th Century, #Upper Class - United States, #United States, #Shipwrecks - North Atlantic Ocean, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Travel, #Titanic (Steamship), #History

Shortly after the collision, Captain Smith had walked to the wireless room and told operator Jack Phillips that the ship had struck an iceberg and to stand by in case the call for assistance was required. Seemingly unperturbed, Phillips continued sending his messages to Cape Race and casually told Harold Bride when he came on duty at midnight that the ship might have to go back to Belfast for repairs. When the captain returned at approximately twelve-twenty-five, Phillips came out of the sleeping quarters.

“

You had better get assistance,” Smith announced grimly.

“Do you want me to use a distress call?” Phillips asked.

“Yes, at once,” the captain replied and left.

Phillips took the piece of paper with the

Titanic

’s position that Fourth Officer Boxhall had brought in earlier and began tapping out the distress signal

CQD

, repeating it six times followed by

MGY

, the

Titanic

’s call letters. Then he sent:

Have struck an iceberg. We are badly damaged, Titanic. Position 41°44′N, 50°24′W

.

About five minutes later the captain came back to the Marconi Room.

“

What are you sending?” he asked.

“

CQD

,” Phillips replied.

“Send

SOS

,” Harold Bride interjected. “It’s the new call, and it may be your last chance to send it.” All three men laughed, and Phillips later began tapping out both

SOS

and

CQD

. Though

SOS

was indeed a new call, it was

not, as is often claimed, the first time it had been used by a ship in distress.

While Phillips listened for replies, the first lifeboats on the starboard side were swung out. When Lifeboat 7 was flush with the deck, First Officer Murdoch and Fifth Officer Lowe called out for ladies to step forward. But very few complied. William Sloper and his bridge companions stood in a group of passengers who were huddled for warmth against the wall near the entrance door. As the crowd moved toward the lifeboat, most people balked and turned away. Murdoch called out that it was perfectly safe as the sea was quite calm. He added that once the damage had been assessed they would be brought on board again. Yet not many wanted to leave the warmth and security of the ship for a freezing excursion in a small open boat.

But Dorothy Gibson was not one of them. She was certain the

Titanic

was going to sink and kept repeating hysterically, “

I’ll never ride in my little gray car again!” William Sloper tried to calm the prettiest girl and helped her into the bow of Lifeboat 7, while Frederic Seward placed Dorothy’s mother in a seat nearby. Dorothy clung to Sloper’s hand and insisted that he come, too. After a nod from Murdoch, both Sloper and Seward stepped into the boat. Sloper later wrote that they then sat for ten minutes looking up at the uncertain faces of passengers standing on the deck.

Helen Bishop, the young newlywed from Dowagiac, Michigan, claimed that she and her husband, Dickinson, were pushed into Boat 7 after an officer took her arm and told her to be very quiet and to get in immediately. Helen had earlier left her lapdog Frou Frou in their room, even though the little dog had tugged at the hem of her dress while she was putting on her life preserver. Thinking it would be inappropriate to take her pet, Helen had closed the stateroom door to the sound of her tiny dog’s high-pitched barks. But another young woman was not going anywhere without her Pomeranian. Twenty-four-year-old Margaret Hays of New York had taken her little dog along on a European tour she had just completed with a school friend and her mother. When the three women decided to dress and go up to the boat deck, Margaret wrapped her pet in a blanket and took it with her. Near the staircase on C deck they were greeted by Gilbert Tucker, a young magazine editor and writer from Albany, New York, who had developed a crush on Margaret. Tucker was holding three lifebelts which he proceeded to help Margaret and the two others to put on. When Jim Smith passed by and saw this, he quipped, “

Oh, I suppose we ought to put a life preserver on the little doggie, too!” Tucker and the three women then proceeded to the boat deck, where all four, along with the little doggie, were permitted to enter Lifeboat 7.

“Any more ladies?” Murdoch called out through his megaphone. When none were forthcoming, the sculptor Paul Chevré and two of his French card-playing companions came forward and were allowed to get in. Lifeboat 7 now held over thirty people, roughly half of its capacity of sixty-five.

At twelve-forty Murdoch instructed the crewmen to let out the ropes around the iron bitts on the deck and lower the first of the

Titanic

’s lifeboats down the side.

When the next boat forward, Lifeboat 5, was being swung out, Third Officer Herbert Pitman noted how easily the davits worked compared to the older ones he had used on other ships. Thirty-four-year-old “Bert” Pitman, a farmer’s son from Somerset, had been working on ships since he was eighteen. The

Titanic

’s new Welin davits were indeed state-of-the-art and were actually equipped to carry more than the one boat each held. But outdated British Board of Trade regulations required a ship the size of the

Titanic

, which could accommodate 3,511 people, to have only sixteen lifeboats, for a maximum of 962 passengers. White Star had actually exceeded the regulations by including four Engelhardt boats with collapsible canvas sides, making room for a total of 1,178. Yet even if all of the

Titanic

’s boats had been filled to capacity, there would only have been places for slightly more than half of the 2,209 on board. No one had imagined a situation where such a watertight ship would need to be wholly evacuated before help could arrive.

Pitman thought that lowering the lifeboats was mainly a precaution. He had therefore been surprised when a tall, mustached man had come up to him while he was uncovering Lifeboat 5 and announced ominously, “

There is no time to waste.” When the boat was ready for boarding, the tall man returned and told Pitman he should load it immediately with women and children. Pitman replied tartly that his orders came from the captain. After the man walked away, it dawned on the third officer that he might have just rebuffed J. Bruce Ismay. He scurried forward to the bridge and told Captain Smith that a man he suspected was Bruce Ismay had told him to get his boat away.

“Go ahead, carry on,” Smith replied calmly.

“

Come along, ladies,” Pitman called out after returning to Lifeboat 5 and stepping into it. A number of men and women walked forward and climbed in. Bruce Ismay approached Karl Behr, who was standing nearby with Helen Newsom and her mother and stepfather and urged them to get in as well.

“

Can the men come too?” asked Helen’s mother, Sallie Beckwith.

“Of course Madam, every one of you,” Ismay replied. Karl Behr then assisted the Beckwiths and Helen Newsom into the boat along with their friends, the Kimballs of Boston, before getting in himself. Henry and Annie Stengel, a middle-aged couple from Newark, New Jersey, also came forward. Henry put his wife into the boat but stood aside when Pitman said the boat was full. Dr. Henry Frauenthal, the New York orthopedist who had treated René Harris’s arm earlier that evening, brought his wife Clara and put her in the lifeboat while he and his brother Isaac remained on the deck. Isaac had been Henry’s best man at his wedding to Clara in Nice only two weeks before.

When Lifeboat 5 had nearly forty people in it, First Officer Murdoch approached and said to Pitman, “

You go ahead in this boat and hang around the after gangway.” Murdoch shook his hand and wished him good luck. When Pitman called out, “

Lower away,” Bruce Ismay picked up the order and began chanting, “Lower, away! Lower, away! Lower, away!” while waving one arm in circles.

“If you will get to hell out of that I shall be able to do something!” shouted Fifth Officer Lowe in indignant, Welsh-accented tones. “Do you want me to lower away quickly? You will have me drown the whole lot of them!” Like Pitman earlier, Lowe had no idea who this meddling person was.

As a chastened Ismay walked away, the lifeboat began its descent. Just then, Henry Frauenthal jumped down into it, followed quickly by his brother, Isaac. According to Annie Stengel, the large “Hebrew doctor” landed on her, knocking her unconscious and dislocating two of her ribs. As Boat 5 continued its descent, the first distress flare rocketed into the sky and burst above the forward funnel in a shower of stars accompanied by a loud bang. The noise alarmed many of the passengers standing on the boat deck.

“

They wouldn’t send those rockets unless it was the last,” remarked Emily Ryerson to her husband. “

Don’t you hear the band playing?” he replied, trying to calm her. The ship’s orchestra, which had begun playing earlier in the lounge, had now moved to the boat deck foyer and cheerful ragtime tunes drifted across the deck. The music was reassuring, and so was the sight of another ship’s mast lights off the port side, making it seem as if rescue was at hand.

The lights of the

Californian

did indeed seem tantalizingly close. But the steamer was not responding to the

Titanic

’s

CQD

calls because its Marconi operator had turned off his equipment and gone to bed over an hour before, after being told to “Shut up” by Jack Phillips. Fourth Officer Boxhall had tried signaling the ship with a Morse lamp but had received no response. He was relieved when Quartermaster Rowe arrived carrying more distress rockets. Surely the ship would see these and come over. “

Fire one, and then fire one every five or six minutes,” Captain Smith ordered. Boxhall continued flashing with his lamp between rocket bursts.

Meanwhile, Frank Millet, Archie Butt, Clarence Moore, and an unknown fourth man continued their card game in the smoking room, seemingly oblivious to all that was going on. At twelve-thirty the smoking room steward had announced, “

Gentleman, the accident looks serious. They are lowering away the boats for women and children.” After that, even the professional gamblers had evacuated the room, but when Archibald Gracie looked in about ten minutes later, he saw Archie’s table still at cards. To Gracie it seemed as if they “

desired to show their entire indifference to the danger and that if I advised them as to how seriously I regarded it, they would laugh at me.” At approximately twelve-forty-five, however, the four men were seen exiting the smoking room by their dining room steward, Fred Ray. It was perhaps then, when they saw passengers standing gathered in lifebelts and noticed the list in the floor, that Archie and Frank fully grasped how serious things had become. In the A-deck staircase foyer Marian Thayer noticed Archie walking toward the stairs with what she called “

a strange unseeing look on his face.” She caught hold of his coat and said, “Major Butt, Major Butt, where are you going? Come with me.”

“I have something to do first but will come then,” Archie replied distractedly, heading down to his stateroom.

“He has gone for his letters,” Marian Thayer thought to herself.

At dinner Archie had spoken to her about how much he valued his letters, yet it was most likely the official communications for President Taft that were preoccupying him now. In his cabin he either destroyed these letters from the pope and several U.S. ambassadors or decided to tuck them into his tunic. At this time, Archie may have exchanged the dress uniform he had likely worn at dinner for his everyday army uniform. Frank Millet chose not to change out of his evening clothes but added a gray woolen vest that Lily had knitted for him, donned an overcoat, and then took down his lifebelt from the top of his cupboard.

Archie Butt was next seen standing calmly on the starboard boat deck while Lifeboat 3 was being lowered. In this boat were Daisy and Frederic Spedden; their young son, Douglas; his nurse, Elizabeth Burns; and Daisy’s maid. Douglas lay asleep in Miss Burns’s lap clutching his stuffed toy polar bear. “Miss B” had awakened him earlier and told him they were taking a trip “

to see the stars.” Nearby sat Henry Sleeper Harper cradling the little brown Pekingese, Sun Yat-sen. Harper had actually seen the iceberg scrape by his porthole and, over his wife Myra’s objections, had insisted that they both dress and go on deck right away. The long wait to get into a lifeboat seemed endless for Harper, who had been in bed with tonsillitis for most of the voyage. He later described the delay as “

rather like a stupid picnic where you don’t know anybody and wonder how soon you can get away from such a boresome place.” Yet the “boresome” wait saved Harper’s life and that of his handsome Egyptian servant, Hammad Hassab, as well. Thomas Cardeza also got into the boat with his manservant, after his mother, Charlotte, had boarded with her maid. Clearly believing this to be a temporary measure, Mrs. Cardeza had left behind her jewel case and its fabulous contents.

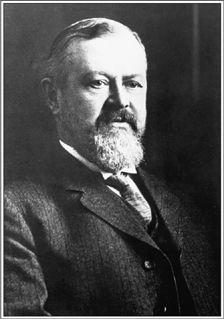

Charles Hays

(photo credit 1.13)

Lifeboat 3 began its descent at twelve-fifty-five, carrying thirty-two people, seventeen of them men. The railroad president Charles Hays stood by with a cigar butt clenched in his teeth as his wife Clara, married daughter Orian Davidson, and his wife’s French-Canadian maid disappeared from view. He had told Orian, “

You and mother go ahead, the rest of us will wait here till morning.” Orian was so reassured by her father’s confidence that she didn’t even think of kissing him or her husband, Thornton, good-bye. The boat began to descend very jerkily since the two crewmen at the ropes were having trouble coordinating the lowering. At one point Daisy Spedden was sure they would be tipped into the sea. “

At last the ropes worked together, and we drew nearer and nearer the oily black water,” recalled another passenger, Elizabeth Shutes. “The first wish on the part of all,” she continued, “was to stay near the

Titanic

. We all felt so much safer near the ship. Surely such a vessel could not sink.”