Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World (31 page)

Read Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World Online

Authors: Hugh Brewster

Tags: #Ocean Travel, #Shipwreck Victims, #Cruises, #20th Century, #Upper Class - United States, #United States, #Shipwrecks - North Atlantic Ocean, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Travel, #Titanic (Steamship), #History

Soon a New York businessman named Abraham Salomon came forward and Murdoch allowed him to join the small group in the boat. The first officer then put two seamen in to handle the oars and, seeing no more passengers on the deck, told five stokers and firemen who were standing nearby that they could jump in too. He put one of the

Titanic

’s lookouts, twenty-four-year-old George Symons, in charge and ordered him to row away from the ship and then to stand by in case they needed to be called back.

As the lifeboat was lowered past A deck it became snagged on a guy wire and Franks recalled

how the boat shook while they were being cut free. On reaching the sea, Lookout Symons was surprised to see that the portholes on D deck were awash and that water was creeping toward the name

Titanic

painted on the bow. He then stood at the tiller as the crewmen rowed away from the ship. In a lifeboat that could have carried forty people there were only twelve, only five of whom were passengers, and only two of them women.

So far, none of the six lifeboats that had left the

Titanic

had been filled to capacity, and none had carried any second- or third-class passengers. Second-class passengers had been told to board from their own promenade area farther aft on the boat deck. Crowds of steerage passengers, meanwhile, were waiting patiently in the well decks, while others sat in the third-class general and smoking rooms, chatting and playing cards. The gates leading up from the aft well deck had been locked to prevent men from third class from going up to the boats. But a number of them had climbed onto the large round bases of the two cargo cranes and were clambering along the arms of the cranes into second class.

As the boats at the aft end of the boat deck began to be swung out, a group of passengers rattled at the locked gates on the stairs that led up from the well deck. A crewman came to the barrier, where Mary Murphy, twenty-five, her teenaged sister, Kate, and their two roommates, Katie Gilnagh, seventeen, and Kate Mullen, twenty-one, peered through.

“

For God’s sake man, let the girls past to the boats, at least!” shouted Jim Farrell, a farmworker from County Longford. The crewman opened the gate for the four Irish girls and then quickly shut it behind them. On reaching the boat deck, Mary Murphy and the three Kates got into Lifeboat 16, the farthest boat aft on the port side. At one-twenty they were lowered down the side with forty-three other women, all from second or third class, along with five crewmen and one baby. Five minutes later, the neighboring portside boat, number 14, began its descent with approximately forty on board. In charge was Fifth Officer Lowe, the volatile young Welsh officer who had bawled out Bruce Ismay by Boat 5 about forty minutes ago. Lowe was now worried that anyone jumping into the heavily loaded boat might cause it to buckle. As the lifeboat descended with Lowe in the stern, he spotted what he later described as “

a lot of Italians, Latin people, all along the ship’s rails … and they were all glaring, more or less like wild beasts, ready to spring.” Lowe took out his revolver and fired several shots along the side of the ship and the “wild beasts” instantly backed off.

Lowe had to act quickly once again when a twist in the lowering ropes caused the stern of the boat to hit the water first while the bow was still pointed five feet upward. He clambered forward and quickly hacked through the ropes until the bow splashed down. Several women screamed but Lowe promptly told them to “

shut up” as he hastened aft to put down the rudder. While Lifeboat 14 pulled away, the next starboard boat, number 12, reached the water with approximately forty on board. On the port side, Boat 9 was also making its descent, carrying another forty people, among them Ben Guggenheim’s mistress, Ninette Aubart, and her maid, and Elizabeth Lines, the woman who had overheard Ismay predicting the

Titanic

’s early arrival, and her daughter, Mary.

It was now just after 1:30 a.m. Ten of the

Titanic

’s sixteen regular lifeboats had departed, carrying approximately 330 people—only a fraction of the 2,209 on board. To the passengers still on deck, the downward slope toward the bow was now very apparent. Yet many of them, the first-class men in particular, still believed that the ship would last till morning and that help would arrive before then. The lights of the nearby ship were still visible—Norris Williams was sure that he could even see the top of its mast above the glowing mast light. And a rumor had been circulating that the sister ship

Olympic

was on its way. In the Marconi Room, Jack Phillips had indeed heard from the

Olympic

, but her position was 500 miles to the east, which meant that she couldn’t arrive till the following night. The German steamer

Frankfurt

had been the first to respond to the

CQD

call, but she was more than 170 miles, and many hours, away. The Cunard liner

Carpathia

was roughly 58 miles from the

Titanic

and had sent a message saying they were coming as quickly as possible and expected to be there within four hours.

Jaunty tunes continued to be played by the ship’s musicians and the music was heard by those in the lifeboats as well as those on deck. Arthur Peuchen heard “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” coming across the water during an awkward silence in Boat 6. The Canadian major had suggested that Quartermaster Hichens let one of the women steer so that he could join them at the oars. The quartermaster erupted at this: “

I am in charge of this boat! It’s your job to keep quiet and row!” A little later Captain Smith’s voice was heard through a megaphone summoning Boat 6 to return for more passengers. Hichens ignored this, saying, “It’s our lives now, not theirs.” Many of the women protested, but a humiliated Peuchen remained silent. “I knew I was perfectly powerless,” he later recounted. “He had been swearing a good deal and was very disagreeable.”

René Harris, too, heard the musicians playing “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” on deck and no doubt thought of how it had been her Harry who had first introduced the tune to New York. She and her “boy” had gone toward various lifeboats as they were being loaded but when told that her husband couldn’t accompany her, René had refused to board. Under her lifebelt she wore her fur coat with one arm dangling and beneath it a flannel blouse from which Harry had cut a sleeve to accommodate her broken arm. The Harrises had gone up on deck with the Futrelles at about twelve-thirty but had then become separated from them.

At one-thirty, Edith Rosenbaum found herself on the boat deck feeling a little perplexed. She had at first waited in the lounge for about forty-five minutes and had then gone up to the boat deck with some other women who were later ordered down to A deck. She had just returned to the upper deck and was wondering if she should get into a lifeboat when a man seized her arm. “

What are you doing here?” he asked. “All women should be off the ship!”

As he pulled her toward a narrow stairway down to A deck, Edith recognized him as Bruce Ismay. At the bottom of the stairs, she was picked up by two crewmen who carried her to the rail of the open promenade and began to thrust her headfirst into Lifeboat 11. When both her velvet slippers fell off she insisted on being put down so she could retrieve them. One of the sailors then grabbed a toy pig she had been carrying under her arm and tossed it into the boat. Edith was very attached to the pig which played a Latin dance tune called “The Maxixe” when its tail was turned; her mother had bought it for her as a good-luck mascot after her car accident. She was eager to retrieve it but climbing into the boat in a silk dress that had a narrow skirt draped to one side was going to be awkward. Seeing her dilemma, a shipboard acquaintance named Philipp Mock stepped forward and gallantly got down on one knee.

“Put one foot on my knee, and your arm around my neck,” he instructed, “and from there you can jump in.” Once Edith was safely on board, Mock joined her and took a seat near his married sister Emma Schabert. Edith found her toy pig lying on the floor; it had two broken legs but could still play “The Maxixe.”

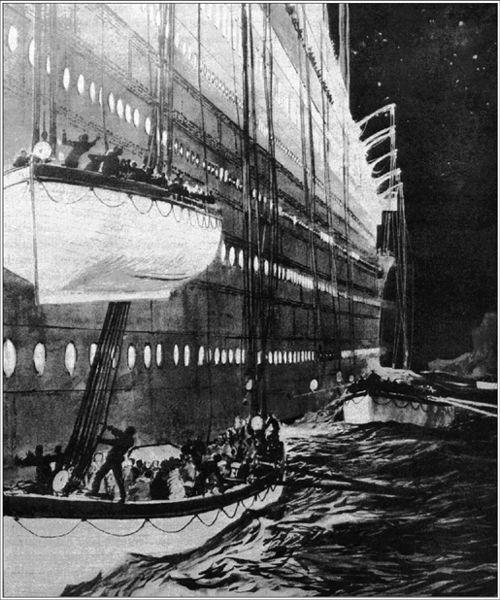

Edith’s boat reached the water at one-forty, just as the two boats from the neighboring davits, Lifeboats 13 and 15, began to come down the side. The London schoolteacher Lawrence Beesley had been allowed into Boat 13, and the crewman in charge was Leading Stoker Fred Barrett, who had twice escaped from flooding boiler rooms that evening—once after the collision and a second time while working the pumps. As his boatload of fifty people made its descent, Barrett was once again faced with gushing water—this time from the condenser exhaust that was spouting from the hull just above the waterline. He shouted up for the lowering to stop while Washington Dodge, a doctor from San Francisco, and two crewmen hunted for the oars, which turned out to be lashed to the seats, with passengers sitting on them. Once the oars were retrieved, Dodge and a few others were able to maneuver the boat out and away from the surging exhaust stream. But the force of it pushed the lifeboat backward until the lowering lines drew taut. The crewmen struggled to free the pulleys at the bow and stern of the boat but the tightened ropes made this difficult. Suddenly, Lifeboat 15 was seen coming down directly on top of them. Cries of “Stop! Stop!” went unheard and soon the keel of Boat 15 was so close that Lawrence Beesley and a stoker in the bow of Boat 13 stood up and tried to push it away with their hands. Fred Barrett jumped toward the ropes at the stern with a knife while another crewman did the same in the bow. To shouts of “One! Two!” they hacked through the lines and freed the boat just as Lifeboat 15 splashed down beside them.

While Boat 13 rowed away, Fred Barrett looked back at the sinking liner with its shining portholes reflected on the calm, black sea and thought that the ship looked like a “

great lighted theatre.” Yet the water lapping at the bow railing made it very clear that this maritime drama was now entering its final act. On the boat deck all but three of the sixteen davits stood empty. The second emergency cutter, Lifeboat 2, was ready for loading on the portside bow but a crowd of stokers had already crawled over the railing into it.

An illustration of Boat 15 coming down on top of Boat 13

(photo credit 1.8)

“

How many of the crew are in that boat?” shouted Captain Smith through a megaphone. “Get out of there, every man of you!”

Mahala Douglas then saw a solid row of men sheepishly crawl out of the boat while Chief Officer Wilde bellowed that they were all “

damned cowards” who should be thrown overboard.

As the call went up for women and children to enter, Mrs. Douglas asked her husband, Walter, to come with her but he refused, pointing to the women who were still on the deck. When the crewmen began gesturing for Mahala to board, she turned to her husband and begged him to come with her but he replied, “

No, I must be a gentleman,” and turned away. Seeing Archie Butt and Clarence Moore standing nearby, she called out, “Walter, when you come, come with Major Butt and Mr. Moore because they are big strong fellows. They will surely make it.” Mahala also spotted Edgar Meyer and Arthur Ryerson in the crowd, and Frank Millet was almost certainly there, too, helping usher women toward the boats as he and his friends had done for most of the last hour. As the last boats were filled, Thomas Andrews was also busy urging women to board:

“Ladies, you

must

get in at once,” he was overheard saying. “There is not a minute to lose. You cannot pick and choose your boat. Don’t hesitate, get in, get in!”

When no more women came forward for Lifeboat 2, the “Lower Away” order was given at one-forty-five. Austrian steerage passenger Anton Kink watched as his weeping wife and four-year-old daughter cried out for him to come with them. As the boat began its descent the black-bearded Kink made a sudden dash and jumped in. Mahala Douglas felt the boat shake as Kink settled down next to his wife and child. She was sitting on the floor in front of Fourth Officer Boxhall, who was at the stern. An officer called down for Boxhall to row over to the starboard side to pick up more passengers since there was room for up to fifteen more in the boat. As they pulled around past the liner’s nearly submerged bow, the fourth officer put Mahala Douglas at the tiller while he helped out with an oar. On arriving on the starboard side, Boxhall thought he sensed the lifeboat being pulled toward the ship, and, fearing the dreaded suction, ordered it to be rowed away.