God's Battalions (10 page)

Authors: Rodney Stark,David Drummond

CONCLUSION

Even if we grant the claims that educated Arabs possessed superior knowledge of classical authors and produced some outstanding mathematicians and astronomers, the fact remains that they lagged far behind in terms of such vital technology as saddles, stirrups, horseshoes, wagons and carts, draft horses and harnesses, effective plows, crossbows, Greek fire, shipwrights, sailors, productive agriculture, effective armor, and well-trained infantry. Little wonder that crusaders could march more than twenty-five hundred miles, defeat an enemy that vastly outnumbered them, and continue to do so as long as Europe was prepared to support them.

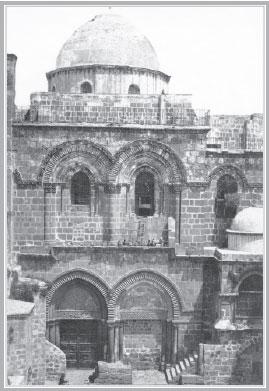

Entrance to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre built over what is believed to be the tomb in which Jesus was buried. The original church was built by Constantine between 326 and 335, but was destroyed by order of the caliph of Egypt in 1009. The present church was built on the ruins of the first, the work beginning in 1037.

©

The Francis Frith Collection / Art Resource, NY

W

HEN POPE URBAN II

called upon the knights of Europe to join God’s battalions, he justified it on the grounds that after many centuries of toleration, Muslims were desecrating the sacred Christian sites in the Holy Land and were inflicting savage mistreatment on Christian pilgrims. Was it true? Or did the pope make it all up? To fully assess these claims it is useful to trace the rise of Christian pilgrimage and to see how Muslims responded to it over time.

EARLY PILGRIMS

Christian pilgrims did not exist in the first century, and had they existed it is not clear where they would have gone. After all, Jesus spent nearly all of his ministry in Galilee and made only several

1

brief visits to Jerusalem. Even so, potential sacred sites in Galilee were not of compelling significance. Eventually Nazareth, Cana, and several other places in Galilee began to attract some pilgrims, and monasteries and churches were built there to commemorate the events involved. But that was later. Meanwhile, although there were extremely sacred sites in Jerusalem, the city had been destroyed by the Romans under Titus in the year 70 and razed again by Hadrian in 135 in the wake of the Bar Kokhba Revolt. So, although early Christians no doubt shared with Jews a special reverence for Jerusalem, we have little knowledge of when Christians began to visit its sacred sites.

What we do know is that pilgrims from the West were never more than a “tiny stream” compared with the “flow of pilgrims to Jerusalem from the East.”

2

Unfortunately, nearly all specific knowledge of Byzantine pilgrims has been lost, so it is the “tiny stream” that we know more about, while we know relatively little about the throngs that came from the Eastern Christian areas.

One early Eastern pilgrim was Melito (died c. 180), bishop of Sardis, who provided the earliest known Christian canon of the Old Testament. Melito visited Jerusalem, and in

Peri Pasha

(“Concerning Passover,” a work that was not discovered until the 1930s) he located major sacred sites in the city. Another visitor was the celebrated Alexandrian theologian Origen (c. 185–254), who traveled in the Holy Land and wrote of “the desire of Christians to search after the footsteps of Christ.”

3

But even though Palestine was relatively close to the major Byzantine cities, there is no evidence that many pilgrims came in early times.

4

That changed with the conversion of Constantine. His mother, the empress Helena, was elevated to sainthood after having visited Jerusalem, where she found many sacred relics and learned that strong local traditions had survived concerning the locations of the important sacred sites. Foremost among these was the belief that Christ’s tomb lay buried beneath a temple of Venus built by Hadrian to spite the Christians.

What followed was one of the very earliest archeological undertakings, well told by the church historian Eusebius (c. 263–339) in his

Life of Constantine.

5

Eusebius began by noting that apparently Hadrian’s engineers had been “determined to hide” the tomb “from the eyes of men…After expending much labor in bringing in earth from outside, they covered up the whole place; then having raised the level of the terrain, and after paving it with stone, they entirely concealed the sacred grotto beneath a great mound.” On top of this the Romans had constructed “a dark shrine of lifeless idols.”

As Eusebius continued: “Constantine gave orders that the place should be purified…And as soon as he issued the orders, these deceitful constructions were torn down…images and demons and all…were overthrown and utterly destroyed…one layer after another was laid bare…then suddenly, contrary to all expectation, the venerable and sacred monument to our Savior’s resurrection became visible, and the most holy cave.” What the excavators seem to have uncovered was a tomb carved into the rock that fit the biblical description.

Constantine’s response was to have the great Church of the Holy Sepulchre constructed over the site, and Eusebius, by then bishop of Caesarea, was present at its consecration. Constantine also had great churches built in Bethlehem and on the Mount of Olives. The discovery of what was believed to be the Holy Sepulchre and Constantine’s other construction projects spurred a rapidly growing stream of pilgrims.

The first of the known pilgrims from the West was a man from Bordeaux (France) who journeyed to the Holy Land in 333, when Constantine’s churches were being finished. We don’t know his name, but he wrote an extended itinerary, which has survived. Much of it is devoted to providing a route and listing good stopping places along the way. He crossed the Alps into Italy and then into Thrace, through Byzantium, across the Bosporus, and on down the coast to Palestine. According to his estimate, it was a trip of about 3,250 miles, and he changed horses 360 times.

6

Once in the Holy Land, the author wrote descriptions of Constantine’s churches and the locations of sacred sites: “On your left [as one heads north toward the city and the Damascus Gate] is the hillock Golgotha where the Lord was crucified, and about a stone’s throw from it, the vault where they laid his body, and he arose again on the third day. By order of the emperor Constantine there now has been built there a basilica…which has beside it cisterns of remarkable beauty, and beside them a baptistery where children are baptized.”

7

In 1884 an Italian scholar discovered a manuscript in a monastery library that was part of a letter written by a woman named Egeria (also Aetheria) who made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land from about 381 to 384. Although some historians have supposed that Egeria was a nun, it seems far more likely that she was a wealthy laywoman who reported her tour of the sights in a letter written to her circle of women friends back home (probably on the Atlantic coast of Gaul). The portion of her letter that survives was copied from the original in the eleventh century by monks at Monte Cassino. No doubt this portion was valued because it describes monks in the Holy Land and their liturgical practices. But the surviving part of Egeria’s letter also reports her visits to many holy sites and side trips to Egypt and Mount Sinai.

In 385 Saint Jerome (340–420) led a group of pilgrims from Rome to the Holy Land. Among them were Bishop Paulinus of Antioch; the wealthy widow Paula and her unmarried daughter Eustochium; and Paula’s good friend, the widow Marcella. Paula was an upper-class Roman matron of immense wealth who had long been part of Jerome’s entourage (which inspired rumors of immorality). After visiting the sacred sites, Jerome and his female circle went to Egypt. But in 388 they returned and took up residence near Bethlehem in a monastery built and funded by Paula. During the last thirty-two years of his life, Jerome lived there and translated the Bible from Greek and Hebrew into Latin.

Oddly enough, Jerome did not think it at all important for anyone to undertake a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, and many early church fathers condemned or ridiculed the practice. Saint Augustine (354–430) denounced pilgrimages, Saint John Chrysostom (c. 344–407) mocked them,

8

and Saint Gregory of Nyssa (c. 335–394) pointed out that pilgrimages were nowhere suggested in the Bible and that Jerusalem was a rather unattractive and sinful city. Jerome agreed, noting that it was full of “prostitutes…[and] the dregs of the whole world gathered there.”

9

But the public paid no attention. When the empress Eudocia (c. 401–460) settled in Jerusalem in 440, it was becoming a very fashionable residence, and women of the nobility dominated the ranks of the pilgrims.

10

Moreover, most pilgrims continued to come from the Byzantine East, it being a very long and expensive trip from the West. Even from Constantinople, it was more than a thousand miles along the Roman roads to Jerusalem.

11

But the numbers kept climbing, and by the end of the fifth century there were more than three hundred hostels and monasteries offering lodging to pilgrims in the city of Jerusalem alone.

12

If we assume that on average each of these could accommodate twenty guests, that would have been a daily capacity of six thousand, which is suggestive of very heavy travel, given that the resident population of the city at that time was only about ten thousand.

13

The upward trend in pilgrim traffic continued through the sixth century, with an increasing number coming from the West by sea. Among them was Antoninus Martyr, who sailed from Italy to Cyprus and then to the coast of Palestine in about 570. In his narrative, he remarks at length on the beauty of Jewish women, and he is the first to report that there were three churches on Mount Tabor in lower Galilee—a claim now supported by surviving ruins.

14

His visit to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre occurred more than two centuries after its original construction, and, according to his descriptions, it had been constantly decorated by pious visitors: “[T]he stone by which the tomb was closed…is adorned with gold and precious stones…its ornaments are innumerable. From iron rods hang armlets, bracelets, chains, necklaces, coronets, waistbands, sword belts, and crowns of emperors made of gold and precious stones, and a great number of ornaments given by empresses. The whole tomb…is covered with silver.”

15

Byzantine embellishments of Jerusalem continued under the celebrated emperor Justinian (483–565), who also greatly expanded Byzantium by “recovering” North Africa, Italy, Sicily, and a portion of southern Spain from various “barbarian” invaders. Justinian built and restored so many buildings in every part of his empire that the ancient historian Procopius (c. 500–565), who was a member of Justinian’s court, wrote an entire book about his constructions.

16

The most monumental of all his buildings was the New Church of Saint Mary, usually referred to as the Nea (new) Church, built in Jerusalem, probably to rival memories of Solomon’s Temple. It was built of enormous blocks of stone, and according to Procopius no other church “can be compared.”

17

Several modern Holy Land archaeologists suspect that the Nea Church served primarily to house the Temple treasures stolen by the Romans in 70 and said to have been recovered by Byzantium at this time.

18

In any event, the enormous complex included a hospice for pilgrims and was a major attraction.

But then it ended.

MUSLIM JERUSALEM

In 636 a Muslim army entered Palestine, and in 638 Jerusalem surrendered. Soon after his triumphant entry into Jerusalem, the caliph ‘Umar wrote a letter of assurance to the city’s population:

This is the covenant given by God’s slave ‘Umar, commander of the believers, to the people of Jerusalem: He grants them security, to each person and his property: to their churches, their crosses, their sick and the healthy, to all people of their creed. We shall not station Muslim soldiers in their churches. We shall not destroy the churches nor impair any of their property or their crosses or anything which belongs to them. We shall not compel the people of Jerusalem to renounce their beliefs and we shall do them no harm.

19

Sounds humane and reasonable. However, the next sentence in this letter reads: “No Jew shall live among them in Jerusalem.”

This seems a very odd prohibition, since Arab sources claim that local Jews had welcomed and often aided the Muslim forces in Palestine.

20

Some suppose that the prohibition was merely an extension of the Byzantine policy precluding Jews from Jerusalem; Saint Jerome revealed that the Jews “are forbidden to come to Jerusalem.”

21

Remarkably, the Byzantines had merely extended the prohibition that Hadrian had first imposed against Jews occupying Jerusalem after he crushed their revolt in 135.

22

As for the Muslims continuing the ban, this was consistent with the prohibition against Jews living anywhere in Arabia and with Muhammad’s persecutions of the Jews in Medina.

23

In any event, a few years later the Muslim rulers dropped this prohibition and allowed Jews to move back into the city. This was at best a mixed blessing, since neither Christians nor Jews could live in Jerusalem—or anywhere else under Muslim rule—unless they accepted the subordinate role of

dhimmi

and were willing to live with the contempt and occasional persecution that that status entailed. “Almost generation after generation, Christian writers recorded acts of persecution and harassment, to the point of slaughter and destruction, suffered at the hands of the Muslim rulers.”

24

In a number of instances, the reports—not only from Christian but also from Muslim sources—implicate the Jewish community as participating in the attacks on Christians.

25

In any event, mass murders of Christian monks and pilgrims were common. An unsystematic list based only on Moshe Gil’s immense

History of Palestine, 634–1099

includes the following events:

- Early in the eighth century, seventy Christian pilgrims from Asia Minor were executed by the governor of Caesura, except for seven who converted to Islam.

- Shortly thereafter sixty pilgrims, also from Asia Minor, were crucified in Jerusalem.

- Late in the eighth century, Muslims attacked the Monastery of Saint Theodosius near Bethlehem, slaughtered the monks, and destroyed two nearby churches.

- In 796 Muslims burned to death twenty monks from the Monastery of Mar Saba.

- In 809 there were multiple attacks on many churches, convents, and monasteries in and around Jerusalem, involving mass rapes and murders.

- These attacks were renewed in 813.

- In 923, on Palm Sunday, a new wave of atrocities broke out; churches were destroyed, and many died.

These events challenge the claims about Muslim religious tolerance.