God's Battalions (5 page)

Authors: Rodney Stark,David Drummond

Table 1.1 shows the number of years required to convert 50 percent of the population to Islam in five major areas. In Iran it took 200 years from the date of the initial conquest by Muslim forces to the time when half of Iranians were Muslims. In the other four areas it took from 252 years in Syria to 264 years in Egypt and North Africa. As to why things happened somewhat more rapidly in Iran, two things set it apart from the other areas. Probably the most important is that for more than a century after falling to Islamic invaders, the Iranians frequently revolted again Muslim rule and did so with sufficient success so that many very bloody battles ensued, as did brutal repressions. These conflicts would have resulted in substantial declines in the non-Muslim population, having nothing to do with conversion. Second, the climate of fear that must have accompanied the defeats of these rebellions likely would have prompted some Iranians to convert for safety’s sake and probably caused others to flee.

In any event, despite the onerous conditions of dhimmitude imposed upon them, the conquered peoples only slowly converted to Islam. Even as late as the thirteenth century, very substantial segments of the populations of the Muslim empire outside of Arabia (where non-Muslims were not permitted) were Christians or Jews. Moreover, most of what has been regarded as Muslim culture and said to have been superior to that of Christian Europe was in fact the persistence of preconquest Judeo-Christian-Greek culture that Muslim elites only slowly assimilated, and very imperfectly (see chapter 3).

CONCLUSION

Many critics of the Crusades would seem to suppose that after the Muslims had overrun a major portion of Christendom, they should have been ignored or forgiven; suggestions have been made about turning the other cheek.

50

This outlook is certainly unrealistic and probably insincere. Not only had the Byzantines lost most of their empire; the enemy was at their gates. And the loss of Spain, Sicily, and southern Italy, as well as a host of Mediterranean islands, was bitterly resented in Europe. Hence, as British historian Derek Lomax (1933–1992) explained, “The popes, like most Christians, believed war against the Muslims to be justified partly because the latter had usurped by force lands which once belonged to Christians and partly because they abused the Christians over whom they ruled and such Christian lands as they could raid for slaves, plunder and the joys of destruction.”

51

It was time to strike back.

TABLE 1.1 | |

AREA | YEARS REQUIRED FOR CONVERSION |

Syria | 252 |

Western Persia (Iraq) | 253 |

Eastern Persia (Iran) | 200 |

Egypt and North Africa | 264 |

Spain | 247 |

Source: Calculated from Bulliet, 1979a, 1979b. |

In 732, a large Muslim army from Spain pushed far north into France, there to be overwhelmed by Frankish troops led by Charles Martel. From then on, the Muslim invaders slowly began to be driven out of Europe.

©

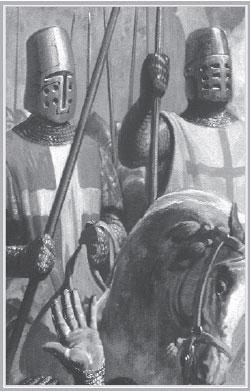

Réunion des Musées Nationaux / Art Resource, NY

D

ESPITE HAVING SO QUICKLY

assembled a large empire out of areas conquered from the Persians, Byzantines, and Visigoths, the Muslim armies were not invincible. When they abandoned their camels and ventured far from the deserts to face loyal and determined Christian forces, the “fierce” and “irresistible” Islamic invaders proved to be quite vulnerable and perhaps deficient in both arms and tactics. The first major Muslim defeat occurred at Constantinople, and then they were routed in Gaul. Soon after that, the Muslim tide began to ebb in Spain, and then they were driven out of Sicily and southern Italy.

DEFEATS AT CONSTANTINOPLE

Having defeated Byzantine armies in Syria and Egypt, and having begun a successful campaign to conquer the entire north coast of Africa from Byzantium, in 672 the caliph Muawiyah decided to strike directly at his enemy. From his new capital in Damascus, the caliph directed his fleet to transport an army through the Dardanelles (the narrow strait linking the Mediterranean with the Sea of Marmara). Numbering about fifty thousand men, the caliph’s troops captured the peninsula of Cyzicus, across the water from Constantinople, and fortified it as their principle base, from where they began a siege of Constantinople.

Had the Muslims taken the city, the way would have been open to invading Europe through the Balkans. But Constantinople easily withstood the siege and inflicted a huge naval defeat on the Muslims. With their fleet destroyed, it was the Arabs who were, in effect, under siege and starving. Soon dysentery became epidemic, and thousands of Muslim soldiers died. Worse yet, few Muslims had ever seen snow or ice, and when winter came they were entirely unprepared. Having no warm clothing, many froze to death. Even so, the Muslims hung on for several years, their ranks continuing to thin while well-fed Byzantines taunted them from the walls of Constantinople. Finally, with his army marooned, “discouraged and demoralized,” Muawiyah accepted Byzantium’s “offer of peace—under terms which, a few years before, he would have considered ignoble: the evacuation of the Aegean islands he had so recently conquered, plus an annual tribute to the Emperor [of Byzantium] of fifty slaves, fifty horses, and 3,000 pounds of gold.”

1

A year later Muawiyah died, and the new caliph soon reneged on the annual tribute payments.

Western historians have long hailed this as “a turning point in the history of mankind.”

2

The Russian-born Byzantine scholar George Ostrogorsky (1902–1976) characterized the attack on Constantinople as “the fiercest which had ever been launched by the infidels against a Christian stronghold, and the Byzantine capital was the last dam left to withstand the rising Muslim tide. The fact that it held saved not only the Byzantine Empire, but the whole of European civilization.”

3

Or as the distinguished historian of Byzantium Viscount John Julius Norwich put it: “Had they captured Constantinople in the seventh century rather than the fifteenth, all Europe—and America—might be Muslim today.”

4

How was this Byzantine victory achieved? Unfortunately, Arab sources are “so confused as to be valueless.”

5

Hence, we know little from the Muslim side, and the Greeks observed Muslim forces only from a distance, safe behind their battlements. That may not be very important since, perhaps surprisingly, there wasn’t all that much fighting, victory being a triumph of Western technology—of impenetrable fortifications

6

and a secret offensive weapon.

7

The walls of the city not only defended Constantinople on the land side but enclosed the three seaward sides of the city as well, even including the harbor, which could be entered only through a massive gate. These were not merely walls; they were an engineering marvel: a massive outer wall with towers and superb battlements and behind it an even stronger inner wall, forty feet high and fifteen feet thick, having even more elaborate battlements and towers. If that weren’t enough, on the landward side there was a huge moat, and, of course, on the other three sides attackers could reach the walls only by boat. Against these extraordinary fortifications, the Arabs brought siege engines that were quite primitive, even for the times, and able to inflict nothing more than small gouges and scratches on the walls. Until attacked by heavy artillery in the fifteenth century, the walls of Constantinople could only be scaled, not shattered.

Of course, the Muslims might have been able to starve the city into surrender had they retained their control of the seas. But that’s where the secret weapon came in.

Tradition has it that in about 670 a Greek architect or engineer named Kallinikos of Heliopolis invented something that has come to be called “Greek fire” and took it to Constantinople. Greek fire was a highly flammable liquid, somewhat akin to napalm, that burst into flames and could not be extinguished by water; it may have burned even more intensely when it came in contact with water. The story of its invention seems a folktale; more likely it was developed by “chemists in Constantinople who had inherited the discoveries of the Alexandrian chemical school.”

8

In any event, the formula was a very closely held secret that eventually was lost when the Fourth Crusade caused many untimely deaths among the ruling elite in Constantinople,

9

and modern scientists have never been able to fully duplicate the effect.

10

Possession of Greek fire allowed the Byzantines to destroy opposing fleets as well as terrorize opposing armies. It was delivered in several ways, but most often by catapult or by a pumping device. A glass or pottery container of Greek fire was loaded onto a catapult and then hurled toward a target as distant as four or five hundred yards. When it struck, it shattered and burst into flames, splashing its blazing liquid over a considerable area—perhaps as far as seventy-five feet in diameter. This was immensely effective when hurled from the battlements of Constantinople and soon discouraged the Muslims from approaching the city. However, catapults are not well suited for use from boats. So the Byzantine engineers invented a primitive flamethrower—a pump that discharged a stream of flaming liquid through a tube projecting from the bow of a galley. (These tubes often had animal heads.) This system had quite limited range but was more than adequate for the close-quarters action of galley warfare. Armed with pumps spewing Greek fire, the Byzantines rowed out and burned the Muslim navy to a cinder—several times.

11

In 717 the Muslims tried once more. This time they came in even greater numbers aboard as many as eighteen hundred galleys. The Greeks lured them into the Bosporus by removing the huge chain used to block entry, and when the Muslim fleet was packed together in these narrow waters out came the Byzantines with their Greek-fire pumps and destroyed most of the fleet, killing or drowning most of the troops aboard. The Muslims tried again the next spring with a new fleet. The Byzantines came out spouting Greek fire again. Some Muslim galleys managed to flee, only to be caught in a devastating storm. In the end, only five Muslim galleys managed to survive.

12

THE BATTLE OF TOURS/POITIERS

As they so often have throughout history, the Pyrenees Mountains served as a barrier that contained the Muslim advance in northern Spain—for a few years. But in 721, Al-Samh ibn Malik al-Khawlani, the Muslim governor of Spain, led his troops north, intent on annexing the duchy of Aquitaine in southern Gaul (now France). His first step was to lay siege to the city of Toulouse. After three months, with the city on the brink of surrender, Duke Odo of Aquitaine arrived with an army of Franks. While Odo had been away gathering his forces, lack of opposition had encouraged Muslim arrogance, setting them up for a devastating defeat. They had constructed no defenses around their camp, had sent out no scouts to warn of an approaching threat, and may not even have posted sentries. Taken completely by surprise when the Franks attacked, the Muslims fled, many without their weapons or armor, and most of them were slaughtered by Frankish cavalry as they ran away. Al-Samh ibn Malik al-Khawlani was mortally wounded.

In 732, led by ‘Abd-al-Rahmân, the Muslims tried again, this time with a far larger force. Muslim sources claim it was an army of hundreds of thousands, and the Christian

Chronicle of St Denis

recorded that three hundred thousand Muslims died in the battle! More realistic is Paul K. Davis’s estimate of an army of eighty thousand Muslims,

13

while Victor Davis Hanson thinks there were only about thirty thousand.

14

In any event, contrary to some historians who want to minimize the importance of the engagement,

15

this was no mere raid or exploratory expedition. The Muslims came with a large army and drove deep into Gaul: the battle occurred only about 150 miles south of Paris, although it is uncertain precisely where it was fought. The best that can be done is to place it near where the rivers Clain and Vienne join, between Tours and Poitiers. Thus some historians refer to it as the Battle of Tours, while others call it the Battle of Poitiers.

As they moved north from Spain, everything went very well for the Muslims. A company of Franks attempting to defend Bordeaux was defeated, and the city was plundered. Then another small Christian army was slaughtered at the Battle of the River Garonne. Along the way, the Muslim army laid waste to the countryside, and soon they were heavily burdened with booty and plunder.

At this point, according to Isidore of Beja’s contemporary account, the Muslim commander “burned churches, and imagined he could pillage the basilica of St. Martin of Tours.”

16

But first he paused to regroup. Once again the Muslims were brimming with confidence. According to an anonymous Arab chronicler, “The hearts of ‘Abd-al-Rahmân, his captains and his men were filled with wrath and pride.”

17

Hence, they sent out no scouts and failed to detect the approach of Charles Martel, de facto ruler of Gaul, leading an army of battle-hardened Franks.

Martel was an unusually tall and powerfully built man, the bastard son of King Pippin and famous for his military exploits. Even had he not confronted Muslim invaders, Martel would have been a major historical figure for having founded the Carolingian Empire (named for him) by winning many battles against the Bavarians, the Alemanni, the Frisians, and the Saxons—an empire later perfected by his grandson Charlemagne. Now, after gathering his troops, Martel marched south to meet the Muslim threat.

Taking the Muslims completely by surprise, Martel was able to choose a battleground to his liking, and he positioned his dense lines of well-armored infantry on a crest, with trees to the flanks, thus forcing the Muslims to charge uphill or refuse to give battle. And charge they did. Again and again.

It is axiomatic in military science that cavalry cannot succeed against well-armed and well-disciplined infantry formations unless they greatly outnumber them.

18

The effective role of cavalry is to ride down infantry fleeing the battlefield, once their lines have given way. But when determined infantry hold their ranks, standing shoulder to shoulder to present a wall of shields from which they project a thicket of long spears butted in the ground, cavalry charges are easily turned away; the horses often rear out of control and refuse to meet the spears. In this instance, the Muslim force consisted entirely of light cavalry “carrying lances and swords, largely without shields, wearing very little armor.” Opposing them was an army “almost entirely composed of foot soldiers, wearing mail [armor] and carrying shields.”

19

It was a very uneven match. As Isidore of Beja reported in his chronicle, the veteran Frankish infantry could not be moved by Arab cavalry: “Firmly they stood, one close to another, forming as it were a bulwark of ice.”

20

The Muslim cavalry repeatedly rushed at the Frankish line, and each time they fell back after suffering severe casualties, with increasingly large numbers of bleeding and riderless horses adding to the confusion on the battlefield.

Then, late in the afternoon, as the Arab chronicler reported, many Muslims became “fearful for the safety of the spoil which they had stored in their tents, and a false cry arose in their ranks that some of the enemy were plundering the camp; whereupon several squadrons of the Muslim horsemen rode off to protect their tents.”

21

To other units this appeared to be a retreat, and it soon became one, during which the Franks unleashed their own heavily armored cavalry

22

to inflict severe casualties on the fleeing Muslims; at least ten thousand of them died that afternoon, including ‘Abd-al-Rahmân, who was run through repeatedly by Frankish lancers.

23

Even during the rout, the Frankish infantry left the pursuit to their cavalry and maintained their discipline, remaining firmly in position, finally spending the night lying in their ranks. In the morning no Muslim forces reappeared. After very carefully scouting the Muslim camp, the Franks learned that during the night the Muslims had fled, leaving empty tents behind them.

Many historians have regarded the victory at Tours/Poitiers as crucial to the survival of Western civilization. Edward Gibbon supposed that, had the Muslims won at Tours, they would soon have occupied “the confines of Poland and the Highlands of Scotland…and the Arabian fleet might have sailed without a naval combat into the mouth of the Thames. Perhaps interpretation of the Koran would now be taught in the schools of Oxford, and her pulpits might demonstrate to a circumcised people the sanctity and truth of the revelation of Mahomet.”

24

Subsequently, many Western historians have taken a similar view of the battle as a major historical turning point; indeed, the German military historian Hans Delbrück (1848–1929) wrote that there was “no more important battle in world history.”

25