Going Rouge

Authors: Richard Kim,Betsy Reed

Going Rouge:

Sarah Palin—An American Nightmare

GOING ROUGE:

Sarah Palin— An American Nightmare

Edited by Richard Kim and Betsy Reed

First published by OR Books, New York 2009

© the collection: Richard Kim and Betsy Reed

© individual pieces: the contributors

(see credits, page 333)

OR Books

www.ORbooks.com

ISBN 978-0-9842950-0-5 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-9842950-1-2 (e book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from

the Library of Congress

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from

the British Library

Printed by Book Mobile, USA

Richard Kim and Betsy Reed

The GOP’s Gift to America

JoAnn Wypijewski

Jane Mayer

Gloria Steinem

Palin’s Real Record

Max Blumenthal and David Neiwert

Michelle Goldberg

Mark Hertsgaard

Michael T. Klare

Sheila Kaplan and Marilyn Berlin Snell

John Nichols

Brentin Mock

Elstun Lauesen

Shannyn Moore

Jeanne Devon

Compiled by Sebastian Jones

Compiled by Sebastian Jones

Hart Seely

4/ LIPSTICK ON A FAUX FEMINIST

Palin and Women

Katha Pollitt

The F-Card Won’t Wash: Sarah Palin Is Disastrous for Women’s Rights

Jessica Valenti

Amy Alexander

Linda Hirshman

Amanda Fortini

Sex, God, and Country First

Dana Goldstein

Hanna Rosin

Gary Younge

Patricia J. Williams

Tom Perrotta

Max Blumenthal

Jeff Sharlet

Matt Taibbi

Jim Hightower

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Thomas Frank

The World According to Sarah

Naomi Klein

Eve Ensler

Juan Cole

AlterNet Staff

A Woman’s Right to Lose

Rebecca Traister

Emily Bazelon

Michelle Goldberg

Katha Pollitt

Dahlia Lithwick

Lingering in the Body Politic

Frank Rich

Joe Conason

Rick Perlstein

Robert Reich

John Nichols

Jane Hamsher, Christopher Hayes, Amanda Marcotte, Michael Tomasky

INTRODUCTION

Richard Kim and Betsy Reed

On the evening of November 4, 2008, progressives were in an ebullient mood. After eight long years of Republican rule, Barack Obama had been elected president. Accompanying our shouts of joy were audible sighs of relief. The prospect of a John McCain presidency had filled us with dread. But to imagine Sarah Palin—a conservative Christian with a penchant for folksy warmongering who flaunted her ignorance as a virtue—separated from the red button in the Oval Office only by a 72-year-old cancer survivor...

that

was beyond terrifying. Palin, we hoped, would slink back to Alaska, where her corrosive influence could be contained and perhaps ultimately extinguished, as her candidacy, historic in its way, became a footnote in an election filled with other, more galvanizing political developments.

As we write, it has been one year since that memorable night, and if the hard realities of governing a nation engulfed in two wars and a deep recession have somewhat dampened the hopes Obama raised during his campaign, another gnawing realization has crept in: The story of Sarah Palin is far from over. Her abrupt announcement over the July 4 weekend that she was quitting the governorship of Alaska may have removed her from public office, but it did little to diminish her presence in the public eye. Her memoir,

Going Rogue

, with a first printing of 1.5 million copies, became a best seller thanks to preorders before it even hit the stores. While her approval rating among all voters hovers around 40 percent, among Republicans it still stands at the 70 percent mark. Disgruntled former McCain staffers continue to snipe at her in the press, but she consistently ranks in the top tier of Republican presidential hopefuls. McCain’s campaign manager Steve Schmidt—who sanctioned her selection as McCain’s running mate—has said that a Palin presidential bid would be “catastrophic,” but McCain himself recently acknowledged that Palin is a “formidable force in the Republican Party” and a strong contender for the party’s nomination in 2012. Compared to the all-male also-rans and might-have-beens that pop up in Republican straw polls—Mitt Romney, Mike Huckabee, Tim Pawlenty, Bobby Jindal, Ron Paul, and Rudy Giuliani—Palin is a bona fide celebrity. She transcends politics. As

New York Times

columnist Frank Rich puts it, Palin is “not just the party’s biggest star and most charismatic television performer; she is its

only

star and charismatic performer.”

What explains this enduring allure? Her gender? Good looks? Her small-town Alaskan roots? Her fascinating biography and family drama? Undeniably, these are all part of the Sarah Palin mystique. Her name instantly conjures up a pungent brew of images, phrases and associations: just an average hockey mom of five, a pit bull with lipstick, beauty queen, moose hunter, long-distance runner, sexy librarian, winker, rogue—you betcha! But for those who care to look, beneath these shimmering surfaces there lies both a crude ideology and an alarmingly potent strategy for selling it. Like Nixon, Reagan, and George W. Bush, Palin has managed to become a brand unto herself, quite a feat for a failed vice presidential candidate. No one speaks of McCainism or Dole-ism, but Palinism signals not just a political position but a political style, a whole way of doing politics.

Palinism works by draping hard-right policy in a winning personal story and just-folks rhetoric, delicately masking the extremism of her true positions and broadening the audience for them. Its genius rests in its ability to magically absorb inconvenient facts and mutually contradictory realities into an unassailable personal narrative. In the Palin universe, her unwed pregnant teenage daughter Bristol is somehow a poster child for abstinence-only education; hence criticism of Palin’s sex-ed policies is an attack on her family. While Palin says tolerantly that members of her own family disagree about abortion, that there are “good people” on both sides, and that she would “personally” counsel a pregnant 15-year-old who’d been raped by her father to “choose life,” she actually believes that a child in that situation should not have the legal option to terminate her pregnancy. Although Palin is an aggressive advocate for opening up the United States’ oil reserves to drilling instead of investing in renewable energy, she labels herself “pro-environment,” a stance exemplified by her love of shooting animals or her husband’s hobby of racing snowmobiles across the tundra. And who’d dare question Palin’s foreign policy credentials, when her son Track shipped out to Iraq after high school?

To grasp the persistent power of Palinism, consider the “death panel” hysteria that hijacked the debate over health care reform in the summer of 2009. It began on July 24, when Betsy McCaughey, the former lieutenant governor of New York and Clinton health care antagonist, took to the pages of the

New York Post

to vilify Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel, the brother of White House chief of staff Rahm Emanuel and a health policy adviser to the Obama administration. Dr. Emanuel, McCaughey wrote, had advocated rationing health care away from the elderly and disabled, and the Democrats’ health care reforms would “put the decisions about your care in the hands of presidential appointees” like him. McCaughey’s claims were easily debunked, and they initially failed to break into the mainstream. That changed on August 7, when Sarah Palin posted a screed against health care reform on her Facebook page that included this classic Palinism: “The America I know and love is not one in which my parents or my baby with Down Syndrome will have to stand in front of Obama’s ‘death panel’ so his bureaucrats can decide, based on a subjective judgment of their ‘level of productivity in society,’ whether they are worthy of health care. Such a system is downright evil.” With remarkable economy of prose, Palin cast health care reform as an assault on the country, put a face on its supposed victims (her baby Trig), coined the expression “death panel” (linking it directly to Obama), raised the specter of euthanasia in the service of a state-run economy, and rallied the troops around a fight against “evil.” In short, she personalized, popularized, and polarized the debate. Never mind that Democratic health care reform bills merely funded optional end-of-life consultations that had heretofore been almost universally acknowledged as a good. (Indeed, Palin herself once championed them in Alaska.) The madness exploded. Astroturf groups funded by the health insurance industry began pumping up the base of tea party protesters, who laid siege to town hall meetings, heckling elected officials from both parties. Fights broke out. Armed zealots began showing up at the president’s speeches. Newt Gingrich appeared on

This Week with George Stephanopolous

and said, “There clearly are people in America who believe in establishing euthanasia, including selective standards.” Other Republican leaders took up the cause, and it was not until Obama flatly rejected death panels as “a lie, plain and simple” in his health care speech on September 9 that the public anxiety over them began to subside.

As this book goes to press, health care reform has yet to pass Congress, and it is unclear what effect the death panel uproar will have on the ultimate legislative outcome. But Palin’s “death panel” crusade has already provided a chilling lesson: that a minority armed with conspiracy theories is capable of occupying the national political discourse as long as they have conviction and a mouthpiece. This brand of politics—hostile to reform in Washington, despite its own reformist posture; unconstrained by any sense of obligation to be truthful and decent when confronting one’s ideological foes—was not invented by Palin, but she has demonstrated a special knack for it ever since she landed on the national scene. During the election, it was Palin who trafficked in guilt by association, dredging up Obama’s reed-thin connection to former Weatherman Bill Ayers and pushing McCain to make the Reverend Jeremiah Wright an issue, despite his pledge to leave Wright out of it. It was Palin who, addressing the surging, angry crowds at her campaign rallies, accused Obama of “palling around with terrorists,” gratifying those who suspected him of being a secret Muslim born outside the country. It was Palin who, while campaigning in North Carolina, praised small towns as “the real America” and the “pro-America areas of this great nation,” fanning racialized fears of urban America and stoking the notion that Obama and his supporters intended a hostile takeover of the U.S. government. And more recently, it was Palin who was among the first to suggest that Obama, in his attempt to alleviate some of the pain caused by the recession, has launched the country on the path to “socialism.” Of course, Sarah Palin does not espouse the entirety of the paranoid right’s propaganda. She does not ask to see Barack Obama’s birth certificate, and she does not show up at town halls toting a rifle and a knife. But she doesn’t have to; suggestion and innuendo are her game, and in the swirl of resentments and phobias that fuel the American right, she is never far from the center.

That Sarah Palin occupies such a vital place in the Republican Party’s zeitgeist—rivaled perhaps only by fellow “outsiders” Glenn Beck and Rush Limbaugh—is even more surprising when one considers the obscurity from which she was plucked by McCain on August 29, 2008. Palin had been mayor of a city of approximately 7,000 and was just twenty months into her first term as governor of Alaska, the forty-seventh-most-populous state in the nation. This was hardly the resume with which to attack Obama for his lack of experience, the McCain campaign’s then going strategy. But a unique set of circumstances convinced McCain’s advisers that choosing Palin was the “game-changing” move they desperately needed to make. The Palin pick was an arrow aimed not only at Obama but at the heart of the fragile Democratic coalition. With the soul-wrenching primary still a raw memory for Democrats torn between a charismatic, visionary black man and a feisty, competent female candidate, McCain’s choice seemed at first to reflect an almost demonic genius. From where progressives stood at that time, Palin appeared to be the latest GOP rabbit-out-of-a-hat, conjured up in some steel-plated war room the likes of which we could scarcely imagine. All those passionate, fresh-faced Obama volunteers with their Facebook pages and house parties that we’d been celebrating as the new transformative force in American politics suddenly seemed pathetic, even tragic, next to the glowing apparition of Sarah Palin on our TV screens.

The spectacle of a woman being elevated to such a lofty place in the Republican Party hierarchy was certainly something to behold. Before her there had been Condoleezza Rice, secretary of state under Bush, and Liddy Dole’s truncated run for the Republican nomination in 2000, among others, but GOP women had been cast either as bit players or members of the team, and now a woman was potentially entrusted with the presidency itself. What’s more, Palin was clearly selected in part because of her womanly appeal. Her nomination was, to be sure, a milestone—finally, a working mother was being celebrated rather than guilt-tripped by family-values traditionalists. But it was also profoundly cynical. Well before McCain’s advisers settled on the choice, Palin’s fortunes were avidly being promoted by besotted male conservatives like the

Weekly Standard

’s Bill Kristol and Fred Barnes, Bush speechwriter Michael Gerson, and consultant Dick Morris, as Jane Mayer reports in her contribution here. The party that congratulated itself for anointing a woman simultaneously embraced a platform advocating draconian restrictions on women’s reproductive freedom (supporting a ban on abortion even in cases of rape, incest, and when the life of the mother is at stake), and its leaders stood against the Lilly Ledbetter act for pay equity, along with every other agenda item for the women’s movement. As pieces in this volume by Katha Pollitt and Gloria Steinem show, feminists were quick to expose the fraudulent nature of the GOP’s gambit. As Steinem put it, “This isn’t the first time a boss has picked an unqualified woman just because she agrees with him and opposes everything most other women want and need.” The small matter of Palin’s utter lack of qualifications for the job would become painfully more apparent as the campaign unfolded. For feminists—who had long heard complaints that affirmative action promotes mediocrity from the same quarters that now extolled Palin’s virtues—the hypocrisy of the pick was too much to bear.

But there she was, the shining star of the Republican National Convention, and indisputably feminine. It was not only Palin herself but the sight of her brood of five children—including baby Trig, and Bristol, 17 and pregnant—along with the ruggedly handsome “first dude” Todd, that riveted the nation. As JoAnn Wypijewski points out in her contribution, Palin and her family are exemplars of the new Christian sexual politics. Married, fertile, God-fearing, and hot: Palin’s sex appeal was a major factor in her bolt to stardom. Finally, conservatives had found a fashionable and sexy icon—why let Hollywood liberals have all the fun?—and if Palin’s looks led some to instantly dismiss her as a pretty airhead, then many others hung on her every wink and word.

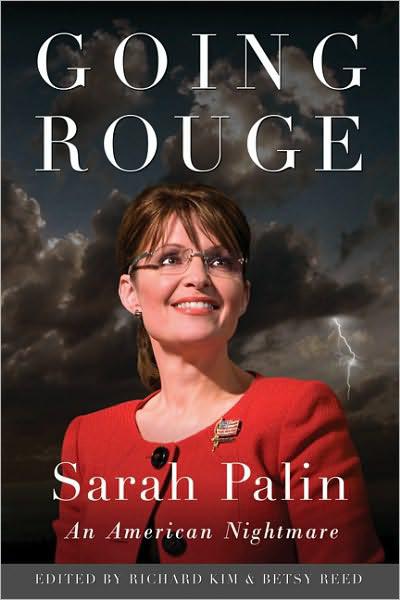

This double-edged effect of her gender and her beauty was on our minds when we selected the title

Going Rouge

for this book. (Appearances aside, it had nothing to do with the fact that Sarah Palin’s forthcoming memoir is called

Going Rogue

; any similarities are purely coincidental.) While we could never be participants in the “Sarah Palin Pity Party” (in Rebecca Traister’s memorable phrase), we are not without sympathy for the bind she has found herself in. In all fairness to Palin, the media attention devoted to her $150,000 shopping spree to glam up her wardrobe—inappropriate though it may have been to use Republican National Committee cash for such a purpose, when the campaign was busy selling her as an Everywoman—was disproportionate. It was not only a frivolous focus at a moment when the financial system was imploding and the U.S. military was waging wars on multiple fronts, but it revealed that Palin was subject to a sort of scrutiny that male candidates are generally spared (yes, John Edwards took flak for his $400 haircuts, but even that had sexist overtones—he was labeled the “Breck Girl” for his excesses). On the other hand, Palin and, by extension, the overwhelmingly white and male Republican Party leadership, having made the decision to “go rouge”—that is, to use her gender and sex appeal to advance their campaign to capture the White House—can’t have expected this remarkable image transformation to pass without criticism, especially when what they stood for was antithetical to most women’s needs and desires.