Goodbye to a River: A Narrative (Vintage Departures) (26 page)

Read Goodbye to a River: A Narrative (Vintage Departures) Online

Authors: John Graves

I looked at it, aware that seldom in my life had I wanted food as I had wanted that hot sugared fruit. Not even those beans on the island …

Hale started laughing. So did I, and remembered with a clarity that I hadn’t felt till then exactly why it was that he was good company, out. It was an awful day. The tent pulled together into a collapsed double-pointed lump finally from the weight of the snow on it. My old shotgun, left in the canoe, gushed water out both barrels when I picked it up. A drifting snag had carried away Hale’s trotline, entire. We got coffee and fruit at last, and stood by the fire steaming ourselves for a couple of hours, and then, the snow thicker than ever, hit the big brown river miserably, the pup a shivering sullen protuberance under the tarp.

The current was fast and shot us down. I remember a big buzzard roost somewhere, the birds hanging like sad black husks in leafless trees, with nowhere to go on a day like that. I remember Hale shooting at three ducks 150 yards away with his magnum twelve, and thousands of the little sad-high-whistling birds in the brush, never showing themselves, and a heron or so, and a place where we stopped and built another big fire and boiled eggs and ate chocolate with them and hung over the fire with sharp animal relish until we knew we had to leave. There was a volunteer watermelon patch at that place of the kind that sprouts where people have had picnics and spat out seeds, but the frosts had touched all the big melons and left only green mush inside them. Hale walked among them smashing them angrily with his gun butt.… I remember most clearly of all the feel of melted snow crawling down the hollow of my back and between my buttocks, and I told him, to put it on record, that if it hadn’t started clearing by the time we reached Dennis I was going to pull out too, for the year.

But the snow stopped not long before we came in sight of the 1892, plank-and-iron, one-way bridge, and blue sky

showed behind us in the west, and at last the yellow setting sun. Soggy, we went into the old ser sta gro there and braved the stares of another set of philosophers while I bought some things I needed.

Outside again, Hale grinned. “When you think up another good joke, you be sure and call me,” he said.

“You picked the worst of it,” I told him.

“Picked, hell. Was picked.”

But it was a measure of how much like me he was in certain childishnesses that he looked wistful as he stood by his car beside the rusty cotton gin, the stringer with its catfish in his hand, and watched us move off downriver. Wistful was the only word for how he looked. The pup stuck his nose out from under the tarp and looked back at Hale until willows intersected the line of sight between us.…

I camped alongside the mouth of Patrick’s Creek in a grove of big elms and oaks where in frontier days and after they used to hold revivals, baptizing by total immersion in the Brazos, horses and guns nearby, and would still if an un-fundamentalistic owner hadn’t fenced them out. I was on the river side of his fence. The hills stand far back from the river there and the bottom is flat rich sandy loam, Southern-looking, the ground stoneless, just sand and mud and the rotting twig-and-leaf carpet of the grove’s floor.

At dusk the brush was full of whitethroats. It was also full of the sad-whistling song that had puzzled me. Ergo, the sad whistler was a … Certainly. Old Sam Peabody, they claimed the song said, and so it did if you pronounced Pea-body in the Yankee way. I supposed the big numbers of them had come in from the north with the cold. The thing was, it was a winter sound in that part of the country, and one tends

falsely to associate bird song with spring, and to learn what little he knows about it then.…

I felt relieved, and again like an amateur naturalist, kinsman to Port Smythe,

M. D

. At Patrick’s Creek, whither our

Red-Skinned Vergil

conducted us at Night Fall, there fell upon our Ear the lugubrious Note of the White-Throated Sparrow,

(Zonotrichia albicollis)…

.

But not much like one. I had no red-skinned Vergil, and all I wanted really, scratch-eyed and chilled, was fire and a drink and bread and bacon. I had them, and went to bed. Owls called, and far off someone was running hounds; scent would be good in the cold fresh-dampened bottom. A wet log on the fire was squirting steam out a tiny sap vein at one end and saying:

Old, Sa-a-am, Peabody, Peabody, Peabody

. Beside me the pup wallowed and made groaning sounds in his regular expression of belly-full contentment. The night before had chipped at his routine—Hale in the tent, and the miserable snow.

Now it was all right, he seemed to be saying. Now it was the way it was supposed to be.

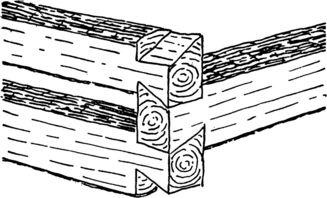

MITER DOVETAIL

CHAPTER TWELVE

IF it hurts it’s probably doing you good. If it’s pleasant it’s most likely wrong. And that twisty road down which life leads you irretraceably farther each day is pocked with dust-disguised holes into which if you step, will you or nill you (most Methodists, for instance, will; pure Presbyterians don’t), you break not your grandmother’s back but your own soul’s.

That certainty rose and spread like a smell from the meetings beneath the oaks and the elms, from brush arbors on the sun-seared, cicada-droning hilltops; the hammer rhythms of the old hymns pulsed it forth:

Far away the sound of strife upon my ear is falling, …

or:

What have I to fear, what have I to dread

,Leaning on the everlasting Arm? …

or:

Whom on earth have I beside Thee

,Whom in Heaven but Thee? …

—that one an old man I know remembers watching his mother sing, with wonder as he watched and heard, since alongside her were ranged in ascending stairsteps of stature the vigorous ninefold issue of her loins.

Just beyond the circle of sacred emanation the saddled horses quivered their hides and switched their tails against long gray flies, and the oaken wagons sat loaded with fried fowl and cornbread and wet-wrapped jugs of buttermilk, and Henrys and Colts lay ready in oiled leather to meet the violence of the unredeemed, red or black or white. And inside the circle, if the sect was one that allowed such doings, old Alfred Tinsley, known as Bug Eye, lay down on the ground and wallowed like the hog he shout-confessed himself to be, and sweated out twelve years of bad whisky, worse language, and what strange women he’d been able to find. It struck home, that religion; it bit. And six months later the ecstatic angry job was there to do over again; fluid evil seeped ever in through the crack that Eve had made in the font, and had to be sloshed away.…

What other brand of godliness, though, would you have substituted for it—in that time, in that place, in that people? A gentle Brahmin reverence for Creation? The flickering-candle mysteries of Rome? The dignified static Episcopalianism of the Old Dominion? Those other ecstasies of fierce locust-eating saints, divorced almost from ethics, above them? Today’s sectless well-wishing?

Besides, it made sinning more fun. Someone must have noted that somewhere, but if so I never saw his notation. If wrong is sharply wrong enough, its edge digs deeper down into the core of that sweet fruit, pleasure, than hedonism ever thought to go. Furtive, itching, hayloft love may have had it all over the silk sheets and mirrors of Paris. It was

sensuality akin to that of the starkly simple liver, and not really separable from it. If anything could make savory the raw corn juice and septic girls of Dodge and Abilene, three months of choking down a steer herd’s dust could—and the rowel of the deadly rectitude of one’s people in Parker County, Texas.…

Up Patrick’s Creek in ’66, the Indians who’d just killed Bohlin Savage to the east and taken his sons found the home of his brother Jim, killed him too, and carried off his little girl as company for her cousins. Raw meat, all the prisoners in the chronicles complained of being forced to live on. It appears to have been much the same underdone protein that backyard brazier-masters pride themselves on these days, but it didn’t look good to frontiersmen, whose descendants even now like their steaks pale gray clear through.… To rouse his appetite for it, little Sam Savage got to ride all the way to the Arbuckle Mountains on a pony with a squaw who carried in her lap the rope-severed head of one of the other Comanches.…

But you don’t want to hear about that. You thought we were through with The People.

So did I.

Let’s be through with them, then, though there’s a lot more that could have been said—about the way smallpox could eat up a tented tribe; about how the buffalo went and their stacked hides stood higher than a horseman’s head for miles in a row at Fort Griffin up the Clear Fork, awaiting shipment; about the last unwise magnificence at the Adobe Walls where a white buffalo hunter made a long long shot over a hill and had the incredible luck to kill the pony of Isatai the prophet; about how Satanta and Satank and Big Tree of the Kiowas massacred Warren’s teamsters at Salt Creek

and pricked the wrath of Yankee General Sherman, which brought Mackenzie, and the trials of Jacksboro, and old Sa-tank shot down singing his soldier song (“O Earth, you remain forever, but we Ka-it-sen-ko must die”) before they got him there, and Satanta a suicide finally in the penitentiary at Huntsville. A lot that could and should have been said about Kiowas as distinct from Comanches, though few whites seem to have minded the difference, and indeed in their thrust and in the completeness of their defeat there was little difference.

Sixteen hundred mangy, beaten Comanches lined up for dole meat at Fort Sill in 1875, their memory of arrogance tamped down in a crevice with stones on top … Let’s be through with them, then. The frontier was. That other People had had its way, and could now swell west and north, or stew in its own juices where it was.