Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974 (40 page)

Read Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974 Online

Authors: James T. Patterson

Tags: #Oxford History of the United States, #Retail, #20th Century, #History, #American History

Hunting for Reds in the 1950s. Reg Manning, March 9, 1953,

Library of Congress

.

The Warren Court at the White House, November 1953. Left to right, front row, are Justice William Douglas, Justice Stanley Reed, Warren, Ike, Justice Hugo Black, Justice Felix Frankfurter. Other justices, back row, are Robert Jackson (3d from left), Tom Clark (4th from left), Sherman Minton (5th from left), and Harold Burton (6th from left). Attorney General Herbert Brownell is far right, back row.

UP, Library of Congress

.

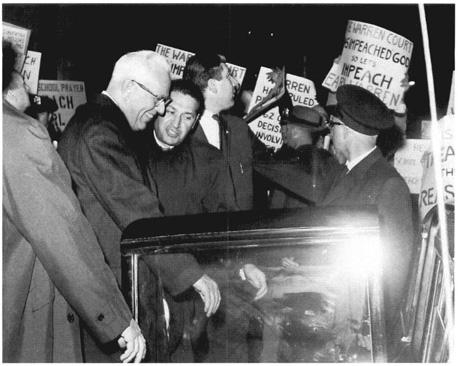

The Supreme Court under siege: Warren and protestors, October 1963.

AP, Library of Congress

.

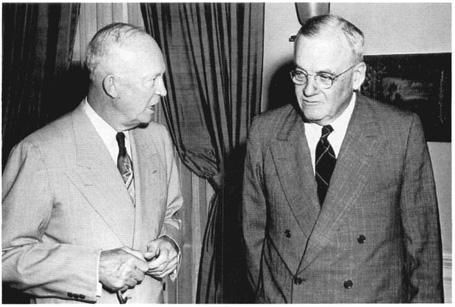

Ike and Secretary of State Dulles. National Park Service,

Eisenhower Library

.

The perils of Brinkmanship. From

Herblock's Special for Today

, Simon & Schuster, 1958.

The "kitchen debate," 1959, Moscow.

AP/Wide World Photos

.

Presidential nominee Adlai Stevenson (r.) and his Democratic running mate, Estes Kefauver, in 1956.

AP, Library of Congress

.

Richard and Pat Nixon, campaigning for the presidency, August 1960.

AP, Library of Congress

.

"conservative when it comes to money and liberal when it comes to human beings," Stevenson—ever quick with a quip—retorted, "I assume what it means is that you will strongly recommend the building of a great many schools to accommodate the needs of our children, but not provide the money."

78

Like most wisecracks in politics, this one was a little unfair. Eisenhower was indeed uninformed on domestic matters when he became President, but he did have a fairly coherent philosophy of government. It was well described in a statement of Abraham Lincoln's that he liked to repeat: "The legitimate aim of government is to to do for a community of people, whatever they need to have done, but cannot do at all, or cannot so well do, for themselves—in their separate, and individual capacities. In all that the people can individually do as well for themselves, government ought not to interfere."

79

What this meant in practice was what his most enthusiastic supporters called "Modern Republicanism." This was a little right of center in emphasis. Believing in limited government, Eisenhower passionately endorsed conservative fiscal policies; balancing the budget and cutting government spending—even on defense—were his highest goals.

80

Curbing spending, in turn, helped bolster his philosophical opposition to federal aid to education, a major cause of liberals in the 1950s, and to "socialized medicine." He sought to cut costly federal price supports to agriculture. He approved legislation returning "tidelands oil," which liberals argued belonged to the national government, to private interests and the states. He wanted above all to decrease the role of government because he believed that large-scale federal intervention threatened individual freedom, the ultimate good in life.

To be conservative did not mean to be reactionary. Eisenhower was emphatic about the distinction between the two. Although he sought to reduce spending, he was not a mindless slasher. The Republican Right complained that he did not cut federal expenditures enough when he took over. (A young conservative senator, Barry Goldwater of Arizona, later said that Ike ran a "Dime Store New Deal.") Like most public figures at the time, the President accepted the need for a little compensatory fiscal policy when the times demanded it. And keeping a close eye on spending was not an abstract end in itself but a means of warding off inflation, which seemed to him (and to many contemporary economists) to be the most worrisome problem during and immediately after the economically stimulating Korean War. This his administration did help to control, and the next few years were remarkably prosperous and stable. Even Galbraith, no friend of GOP economic policy, conceded in January 1955 that "the Administration as a whole has shown a remarkable flexibility in the speed with which it has moved away from these slogans [of balanced budgets]."

81

The President also proved ready to accept a few moderately liberal ventures in the realm of social policy. "Should any political party attempt to abolish Social Security, unemployment insurance, and eliminate labor laws and farm programs," he warned his conservative brother Edgar, "you would not hear of that party again in our political history."

82

He thereupon signed in 1954 a broadening of Social Security. He also sought to extend the minimum wage, which covered fewer than half of the wage workers in the United States. Both programs, of course, were financed primarily by employers and workers—not by federal funds that might increase federal deficits. But Eisenhower in no way threatened the welfare state begun in the New Deal years: social welfare expenditures during his presidency rose slowly but steadily as a percentage of GNP (from 7.6 percent in 1952 to 11.5 in 1961) and (especially after 1958) as a percentage of federal spending.

Beyond these moves lay a larger vision of what the United States should be: a cooperative society in which major groups such as corporations, labor unions, and farmers would set aside their special interests to promote domestic harmony and economic stability. The State, Eisenhower believed, could serve as an arbiter of this cooperative commonwealth, acting to bring excessive special interests together and restraining their demands. As in his dealings with McCarthy, however, Ike shrank from involving the presidency in controversial questions. Better, he thought, to stand above the battle and in so doing preserve his political standing. "Partisanship," moreover, was to Ike a word every bit as dirty as "special interest." He complained that Truman had used "ward-boss, strong-arm tactics" that had not worked and that had diminished the prestige of the presidency. He added, "I am not one of the desk-pounding types that likes to stick out his jaw and look like he is bossing the show. I don't think it is the function of a President of the U.S. to punish anybody for voting as he likes."

83

In holding to this Whiggish view of the presidential role Eisenhower indeed conserved his personal prestige and popularity. If he had tried to push through major domestic legislation, he would surely have provoked determined opposition. Contemporary measures of public opinion indicated that the majority of middle-class (and politically influential) Americans in the early 1950s, especially in the aftermath of the Korean War, did not look to government for great changes. They were tired of the angry controversies of the late 1940s and early 1950s. Developing ever-larger expectations about their personal futures, they were bent on maximizing the substantial economic and educational gains that they were coming to enjoy. Pressure groups, too, resisted change that threatened their standing. It is simply ahistorical to think that Eisenhower, who was elected as a moderate, could have or should have demanded major reforms in the early 1950s.