Grand Opera: The Story of the Met (6 page)

Read Grand Opera: The Story of the Met Online

Authors: Charles Affron,Mirella Jona Affron

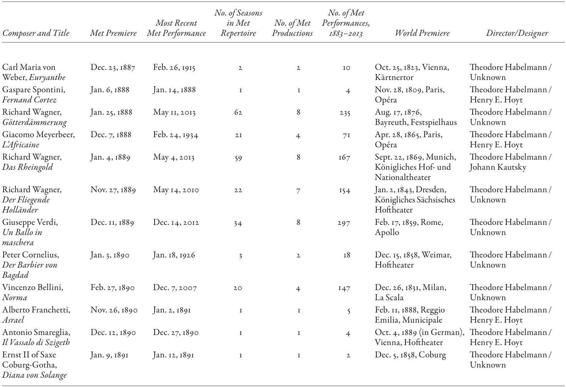

TABLE 2.

Metropolitan Opera Premieres, 1884–85 to 1890–91

(Italian and French operas given in German)

TABLE 2.

(continued)

TABLE 2.

(continued)

In 1892, looking back, Stanton rehearsed his apology for German opera one last time. He began by opposing “old favorite operas” (namely, bel canto) to the “new,” the “modern” (namely, Wagner above all). He aimed his sharpest barbs at the star system; in its place, he had advocated repertory casting and the thorough preparation of chorus and orchestra. He was persuaded that New York operagoers, who had come to expect the high musical and dramatic standards of the German ensemble, “could no more sink back into the enthusiasms that satisfied the audiences of a quarter of a century ago than could our modern theatregoers applaud the mouthing and strutting of the dead histrionic heroes of melodramatic fame.” The public’s affinity for “modern orchestration,” that is, for more contemporary music, had been cultivated by exposure to the symphony. The point of no return was long passed. In conclusion, he taxed the Abbey prescription of stars singing an “old favorite” repertory with “prohibiting the production of opera as an Art-Work.”

7

In Stanton’s first season, and for the next two, 50 percent of the repertoire was given over to Wagner, 70 percent to German works. The German share dipped to over 50 percent in 1888–89, about 60 percent in 1889–90 and 1890–91. In the period 1886–1891, Wagner receipts were higher by 21 percent than the average take of the non-Wagner repertoire, German or not. By the end of the seven years, all the operas of Wagner had been produced by the Met with the exception of two early works,

Die Feen

and

Das Liebesverbot,

and

Parsifal,

until 1903 staged only at Bayreuth’s Festspielhaus. Four years into Stanton’s regime, Henderson gave a rhapsodic assessment of what he considered the ennobling effect of German opera: “Musical amateurs are beginning to understand that this is a serious art form, capable of mighty purposes and almost fathomless meanings. . . . It is beginning to stand in the estimation of thinking men and women beside the most elevated drama and poetry” (

Times,

Jan. 19, 1888).

8

Throughout the German seasons and after, box holders waged a tug-of-war with yet another segment of the operagoing public, “culturist” habitués of the

parquet. The two classes squared off on the code of conduct appropriate to the opera house, a front related to the ongoing culture war over musical taste. Early on,

Musical Courier

(Dec. 10, 1884) threatened to publish the names of those who, like the occupants of prominent boxes at the season’s first

Lohengrin,

chatted and laughed during performances. Two years later, nothing had changed. A satirical piece in

Harper’s

(April 1886) turned the volume up a notch, urging that the philistines who treated the opera house as their private salon repair to “the congenial circles of miners and Indian reservations upon the frontier,” an allusion to the West, where so many recent fortunes had been made. In a reversal of class typology, it was the ill-behaved, well-born, well-heeled, and stubbornly middlebrow box holders who were shown up by the well-behaved, modestly born, middle-class, and highbrow ticket holders. The reviewer goes on to pity those “whom an unkind fate dooms to sit near [the noisemakers].” More circumspect observers, such as Henderson, attempted to mediate what had become “continual warfare” by noting that “like most questions in this world, this has two sides. The stockholders built and maintain the opera house and they have undeniably the right to derive as much pleasure as possible from the fruits of their enterprise.” And after all, compared with the prestige that the presence of high society lent the cause of German opera, “a matter [not] to be lightly considered,” turning the house into a “social resort” was “by no means so heinous a procedure” as some irate opera lovers protested. He proposed a middle ground: “No one objects to talk which is not too loud. If the occupants of the boxes will bear that in mind, neither they nor their valuable friends in the other parts of the house will be annoyed” (

Times,

Dec. 29, 1887). The compromise fell flat. And three years later, the board was obliged to issue the following notice: “Many complaints having been made to the directors of the Opera House of the annoyance produced by the talking in the boxes during the performances, the board requests that it be discontinued.”

9

The stockholders remained disinclined to moderate their deportment. They demanded long intermissions timed not to scene changes, but to leisurely social intercourse, complete with refreshments delivered from a nearby restaurant. Their power was such that the lights in the auditorium were turned up when they complained about the dark, the effect on theatrical illusion be damned. Here Henderson drew the line: “This last fact is a sufficient commentary on any professions of devotion to the laws of art” (

Times,

Jan. 22, 1889). But despite the outrage of much of the public, the lights stayed on. Sightings of those who mattered would have otherwise been foiled, above

all the entrance of Mrs. Astor into box 9 (box 7 after 1892) at precisely 9:00 p.m. on Monday nights. “What she did was copied slavishly by the rest of society,” commented soprano Frances Alda. As a result, more often than not, the first act was sung to a half-empty auditorium; occasionally, the curtain would be held until she arrived. Alda described the moment thus: “As nine o’clock drew near, there would be the swish and rustle of silk trains, the tramp of feet coming down the orchestra aisles, the scrape of chairs being moved to better positions in the boxes. Interest in happenings on the stage dwindled. Opera glasses were raised and focused on the curtains of Box Seven. . . . Mrs. Astor came in and took her seat. An audible sigh of satisfaction passed through the house. The prestige of Monday Night was secure. Only, then, was the attention of all but the ardent music-lovers in the audience turned to the singers and orchestra.” With the same regularity that marked her entrance, at the close of the second intermission, Mrs. Astor made her exit—in time for the competing Monday night Patriarch or Assembly balls.

10

As early as spring 1885, the Wagnerites declared the campaign won. German opera was no longer an “occasional and curious experiment on off evenings and with a chance-medley company,” but a repertoire whose interpretative style had been “approved by and accepted by ‘fashion’ and ‘the town.’” In truth, less than halfway through the German seasons, grumbling among “fashion,” audible from the first, grew louder as stockholders became ever more exasperated with “the town” and what they experienced as a surfeit of Wagner. Nostalgia for the Italian operas of the past kept pace with their increasing hostility. Rising costs rubbed salt into the wounds inflicted night after night by the repertoire. Salaries of German artists had mushroomed over time: Lilli Lehmann’s fee was $600 per performance, Albert Niemann’s $1,000. At the January 21, 1888, meeting of the board, the directors determined that two alternatives be put before the stockholders: to cancel the 1888–89 season, which would have entailed an assessment, or to continue German opera at more than three times the current price per box. The option of an Italian season was judged an extravagance not worth considering. The stockholders agreed to continue German opera. By opening night 1890, Stanton was in still deeper trouble: he had lost his most bankable stars, Lehmann and tenor Max Alvary.

11

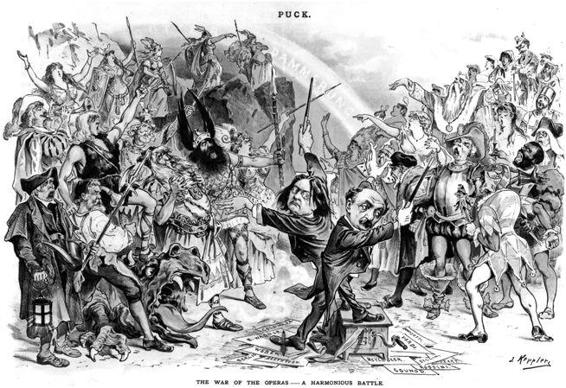

FIGURE 6.

The war between the German and the Italian/French wings,

Puck

cartoon, February 11, 1891 (courtesy Metropolitan Opera Archives)

On January 7, 1891, Henry Abbey, this time with Maurice Grau (a lawyer by training, he had managed the American tours of Anton Rubinstein, Henri Wieniawski, and Jacques Offenbach) and John B. Schoeffel (a silent partner), offered to lease the house once again, guaranteeing a season of sixty shows in Italian and French, and promising Jean de Reszke, Édouard de Reszke, and Nellie Melba, all for $2,000 per performance. With the understanding that there would be no additional assessment, the stockholders voted a decisive yes. As Auchincloss described it, the “revolt . . . against . . . the longueurs of Wagner” had succeeded. “Lilli Lehmann [had] tried to warn Edmund of it; she begged him to make some concessions.” But he had refused. Stanton submitted his resignation. The German era had come to an end. In a long lament for the seven seasons gone by, Henderson held out this caution to Stanton’s successor: “The Italian singer is always a singer, and he conceives it to be his divine right to face the footlights, sing directly to the audience, and dwell on all his high notes. . . . This style of thing, however, is dead in New York” (

Times,

March 22, 1891).

12

Maybe so. But there was no question that Stanton had presided over a disastrous final German year. In a desperate move to address one of the crushing criticisms leveled at his stewardship, that he had failed to deliver on

novelties as stipulated, he staged three New York premieres. The season opened with Alberto Franchetti’s Wagnerian

Asrael;

it ran for five performances to feeble box office and to weak and, in at least two instances, overtly anti-Semitic reviews: “The modern Hebrew composer has the faculty of absorbing, assimilating, call it what you will, the dominating influences of his environment. . . . Look at Meyerbeer and Halévy, consider Mendelssohn and Goldmark, and Franchetti has the advantage over them all—he comes last” (

Musical Courier,

Dec. 3, 1890). Krehbiel, too, was driven to the Meyerbeer analogy: weren’t the two composers both Jewish and wealthy? The second novelty was Anton Smareglia’s

Il Vassalo di Szigeth,

which had four performances and an uneven reception. And finally, and fatally, Stanton presented the thirty-year-old

Diana von Solange,

the inspiration of Ernest II, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. A public outcry forced the cancellation of the run after two performances. Fearing a boycott by the Wagnerites following the announcement of the impending changeover to French and Italian, Stanton scheduled a flurry of twenty-five performances of Wagner out of the season’s remaining thirty-five. Audiences came and vented their anger at the board by cheering Seidl and the German casts at every curtain call.

13