Gravity's Rainbow (25 page)

Authors: Thomas Pynchon

But on the way home tonight, you wish you’d picked him up, held him a bit. Just held

him, very close to your heart, his cheek by the hollow of your shoulder, full of sleep.

As if it were you who could, somehow, save him. For the moment not caring who you’re

supposed to be registered as. For the moment anyway, no longer who the Caesars say

you are.

O Jesu parvule

,

Nach dir ist mir so weh . . .

So this pickup group, these exiles and horny kids, sullen civilians called up in their

middle age, men fattening despite their hunger, flatulent because of it, pre-ulcerous,

hoarse, runny-nosed, red-eyed, sore-throated, piss-swollen men suffering from acute

lower backs and all-day hangovers, wishing death on officers they truly hate, men

you have seen on foot and smileless in the cities but forgot, men who don’t remember

you either, knowing they ought to be grabbing a little sleep, not out here performing

for strangers, give you this evensong, climaxing now with its rising fragment of some

ancient scale, voices overlapping three- and fourfold, up, echoing, filling the entire

hollow of the church—no counterfeit baby, no announcement of the Kingdom, not even

a try at warming or lighting this terrible night, only, damn us, our scruffy obligatory

little cry, our maximum reach outward

—praise be to God!

—for you to take back to your war-address, your war-identity, across the snow’s footprints

and tire tracks finally to the path you must create by yourself, alone in the dark.

Whether you want it or not, whatever seas you have crossed, the way home. . . .

• • • • • • •

Paradoxical phase, when weak stimuli get strong responses. . . . When did it happen?

A certain early stage of sleep: you had not heard the Mosquitoes and Lancasters tonight

on route to Germany, their engines battering apart the sky, shaking and ripping it,

for a full hour, a few puffs of winter cloud drifting below the steel-riveted underside

of the night, vibrating with the constancy, the terror, of so many bombers outward

bound. Your own form immobile, mouth-breathing, alone face-up on the narrow cot next

to the wall so pictureless, chartless, mapless: so

habitually blank. . . .

Your feet pointed toward a high slit window at the far end of the room. Starlight,

the steady sound of the bombers’ departure, icy air seeping in. The table littered

with broken-spined books, scribbled columns headed

Time

/

Stimulus

/

Secretion (30 sec)

/

Remarks

, teacups, saucers, pencils, pens. You slept, you dreamed: thousands of feet above

your face the steel bombers passed, wave after wave. It was indoors, some great place

of assembly. Many people were gathered. In recent days, at certain hours, a round

white light, quite intense, has gone sliding along and down in a straight line through

the air. Here, suddenly, it appears again, its course linear as always, right to left.

But this time it isn’t constant—instead it lights up brilliantly in short bursts or

jangles. The apparition, this time, is taken by those present as a warning—something

wrong, drastically wrong, with the day. . . . No one knew what the round light signified.

A commission had been appointed, an investigation under way, the answer tantalizingly

close—but now the light’s behavior has changed. . . . The assembly adjourns. On seeing

the light jangling this way, you begin to wait for something terrible—not exactly

an air raid but something close to that. You look quickly over at a clock. It’s six

on the dot, hands perfectly straight up and down, and you understand that six is the

hour of the appearance of the light. You walk out into the evening. It’s the street

before your childhood home: stony, rutted and cracked, water shining in puddles. You

set out to the left. (Usually in these dreams of home you prefer the landscape to

the right—broad night-lawns, towered over by ancient walnut trees, a hill, a wooden

fence, hollow-eyed horses in a field, a cemetery. . . . Your task, in these dreams,

is often to pens. Often you go into the fallow field just below the graveyard, full

of autumn brambles and rabbits, where the gypsies live. Sometimes you fly. But you

can never rise above a certain height. You may feel yourself being slowed, coming

inexorably to a halt: not the keen terror of falling, only an interdiction, from which

there is no appeal . . . and as the landscape begins to dim out . . . you

know . . . that . .

.) But this evening, this six o’clock of the round light, you have set out leftward

instead. With you is a girl identified as your wife, though you were never married,

have never seen her before yet have known her for years. She doesn’t speak. It’s just

after a rain. Everything glimmers, edges are extremely clear, illumination is low

and very pure. Small clusters of white flowers peep out wherever you look. Everything

blooms. You catch another glimpse of the round light, following its downward slant,

a brief blink on and off. Despite the apparent freshness, recent rain, flower-life,

the scene disturbs you. You try to pick up some fresh odor to correspond to what you

see, but cannot. Everything is silent, odorless. Because of the light’s behavior something

is going to happen, and you can only wait. The landscape shines. Wetness on the pavement.

Settling a warm kind of hood around the back of your neck and shoulders, you are about

to remark to your wife, “This is the most sinister time of evening.” But there’s a

better word than “sinister.” You search for it. It is someone’s name. It waits behind

the twilight, the clarity, the white flowers. There comes a light tapping at the door.

You sat bolt upright in bed, your heart pounding in fright. You waited for it to repeat,

and became aware of the many bombers in the sky. Another knock. It was Thomas Gwenhidwy,

come down all the way from London, with the news about poor Spectro. You slept through

the loud squadrons roaring without letup, but Gwenhidwy’s small, reluctant tap woke

you. Something like what happens on the cortex of Dog during the “paradoxical” phase.

Now ghosts crowd beneath the eaves. Stretched among snowy soot chimneys, booming over

air-shafts, too tenuous themselves for sound, dry now forever in this wet gusting,

stretched and never breaking, whipped in glassy French-curved chase across the rooftops,

along the silver downs, skimming where the sea combs freezing in to shore. They gather,

thicker as the days pass, English ghosts, so many jostling in the nights, memories

unloosening into the winter, seeds that will never take hold, so lost, now only an

every-so-often word, a clue for the living—“Foxes,” calls Spectro

E

across astral spaces, the word intended for Mr. Pointsman who is not present, who

won’t be told because the few Psi Section who’re there to hear it get cryptic debris

of this sort every sitting—if recorded at all it finds its way into Milton Gloaming’s

word-counting project—“Foxes,” a buzzing echo on the afternoon, Carroll Eventyr, “The

White Visitation” ’s resident medium, curls thickly tightened across his head, speaking

the word “Foxes,” out of very red, thin lips . . . half of St. Veronica’s hospital

in the morning smashed roofless as the old Ick Regis Abbey, powdered as the snow,

and poor Spectro picked off, lighted cubbyhole and dark ward subsumed in the blast

and he never hearing the approach, the sound too late, after the blast, the rocket’s

ghost calling to ghosts it newly made. Then silence. Another “event” for Roger Mexico,

a round-headed pin to be stuck in his map, a square graduating from two up to three

hits, helping fill out the threes prediction, which lately’s being lagged behind. . . .

A pin? not even that, a pinhole in paper that someday will be taken down, when the

rockets have stopped their falling, or when the young statistician chooses to end

his count, paper to be hauled away by the charwomen, torn up, burned. . . . Pointsman

alone, sneezing helplessly in his dimming bureau, the barking from the kennels flat

now and diminished by the cold, shaking his head

no

. . . inside me, in my memory . . . more than an “event” . . . our common mortality . . .

these tragic days. . . . But by now he is shivering, allowing himself to stare across

his office space at the Book, to remind himself that of an original seven there are

now only two owners left, himself and Thomas Gwenhidwy tending his poor out past Stepney.

The five ghosts are strung in clear escalation: Pumm in a jeep accident, Easterling

taken early in a raid by the Luftwaffe, Dromond by German artillery on Shellfire Corner,

Lamplighter by a flying bomb, and now Kevin Spectro . . . auto, bomb, gun, V-1, and

now V-2, and Pointsman has no sense but terror’s, all his skin aching, for the mounting

sophistication of this, for the dialectic it seems to imply. . . .

“Ah, yes indeed. The mummy’s curse, you idiot. Christ, Christ, I’m ready for D Wing.”

Now D Wing is “The White Visitation” ’s cover, still housing a few genuine patients.

Few of the PISCES people go near it. The skeleton of regular hospital staff have their

own canteen, W.C.s, sleeping quarters, offices, carrying on as under the old peace,

suffering the Other Lot in their midst. Just as, for their part, PISCES staff suffer

the garden or peacetime madness of D Wing, only rarely finding opportunity to swap

information on therapies or symptoms. Yes, one would expect more of a link. Hysteria

is, after all, is it not, hysteria. Well, no, come to find out, it’s not. How does

one feel legitimist and easy for very long about the transition? From conspiracies

so mild, so domestic, from the serpent coiled in the teacup, the hand’s paralysis

or eye’s withdrawal at words,

words

that could frighten that much, to the sort of thing Spectro found every day in his

ward, extinguished now . . . to what Pointsman finds in Dogs Piotr, Natasha, Nikolai,

Sergei, Katinka—or Pavel Sergevich, Varvara Nikolaevna, and then their children, and—When

it can be read so clearly in the faces of the physicians . . . Gwenhidwy inside his

fluffy beard never as impassive as he might have wished, Spectro hurrying away with

a syringe for his Fox, when nothing can really stop the Abreaction of the Lord of

the Night unless the Blitz stops, rockets dismantle, the entire film runs backward:

faired skin back to sheet steel back to pigs to white incandescence to ore, to Earth.

But the reality is not reversible. Each firebloom, followed by blast then by sound

of arrival, is a mockery (how can it not be deliberate?) of the reversible process:

with each one the Lord further legitimizes his State, and we who cannot find him,

even to see, come to think of death no more often, really, than before . . . and,

with no warning when they will come, and no way to bring them down, pretend to carry

on as in Blitzless times. When it does happen, we are content to call it “chance.”

Or we have been persuaded. There do exist levels where chance is hardly recognized

at all. But to the likes of employees such as Roger Mexico it is music, not without

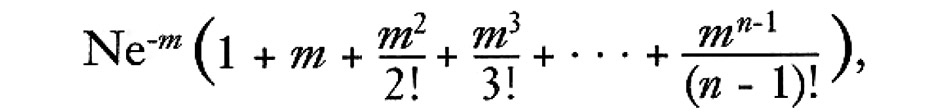

its majesty, this power series

terms numbered according to rocketfalls per square, the Poisson dispensation ruling

not only these annihilations no man can run from, but also cavalry accidents, blood

counts, radioactive decay, number of wars per year. . . .

Pointsman stands by a window, his own vaguely reflected face blown through with the

driven snow outside in the darkening day. Far across the downs cries a train whistle,

grainy as late fog: a cock-crow— ·—·——, a long whistle, another crow, fire at trackside,

a rocket, another rocket, in the woods or valley . . .

Well . . . Why

not

renounce the Book then Ned, give it up that’s all, the obsolescent data, the Master’s

isolated moments of poetry, it’s paper that’s all, you don’t need it, the Book and

its terrible curse . . . before it’s too late. . . . Yes, recant, grovel, oh fabulous—but

before whom? Who’s listening? But he has crossed back to the desk and actually laid

hands on it. . . .

“Ass. Superstitious

ass.

” Wandering, empty-headed . . . these episodes are coming more often now. His decline,

creeping on him like the cold. Pumm, Easterling, Dromond, Lamplighter, Spectro . . .

what should he’ve done then, gone down to Psi Section, asked Eventyr to get up a séance,

try to get on to one of them at least . . . perhaps . . . yes . . . What holds him

back? “Have I,” he whispers against the glass, the aspirate, the later plosives clouding

the cold pane in fans of breath, warm and disconsolate breath, “so much pride?” One

cannot,

he

cannot walk down that particular corridor, cannot even suggest, no not even to Mexico,

how he misses them . . . though he hardly knew Dromond, or Easterling . . . but . . .

misses Allen Lamplighter, who would bet on anything, you know, on dogs, thunderstorms,

tram numbers, on street-corner wind and a likely skirt, on how far a given doodle

would get, perhaps . . . oh God . . . even the one that fell on him. . . . Pumm’s

arranger-style piano and drunken baritone, his adventuring among the nurses. . . .

Spectro . . . Why

can’t

he ask? When there are a hundred ways to put it. . . .