Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India (18 page)

Read Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India Online

Authors: Joseph Lelyveld

Tags: #Political, #General, #Historical, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #Biography, #South Africa - Politics and government - 1836-1909, #Nationalists - India, #Political Science, #South Africa, #India, #Modern, #Asia, #India & South Asia, #India - Politics and government - 1919-1947, #Nationalists, #Gandhi, #Statesmen - India, #Statesmen

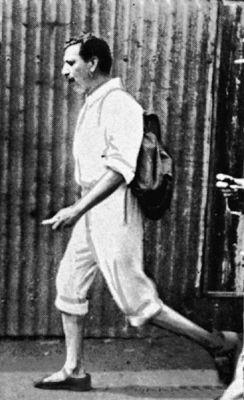

Kallenbach, 1912, striding

(photo credit i4.2)

The original agreement specified that K. would live apart from the settlers and that G. would mostly stay with him. Then Mrs. Gandhi moves up to Tolstoy Farm from Phoenix for a period of more than a year. It’s not clear what effect this has. By then, Ba and her husband have been sleeping in separate quarters for more than five years. At Tolstoy Farm, they sleep on separate verandas, each surrounded by students from Gandhi’s school.

What’s easy to miss in accounts of Gandhi’s life at Tolstoy Farm is how powerful a factor his feeling for Kallenbach has become in the inward turning he has taken. Not only is he bent on reforming this partner, he strives to make their association permanent. The architect wavers. He is living life on two planes. While at Tolstoy Farm with Gandhi, he has also become a Zionist and a more observant Jew; he takes Gandhi to synagogue on Passover and introduces him to matzoh. Some weeks, in preparation for a move to India, he studies Hindi; other weeks, when he wonders how much of Gandhi’s time he’ll be able to own in a still

unimaginable Indian future, he studies Hebrew in preparation for a new life in Palestine. On a day-by-day basis, the surest index to the architect’s changeable mood is which language he’s studying, Hindi or Hebrew. He’s disconsolate, if not jealous, when Gandhi lavishes admiration and time on someone else. Persisting, Gandhi puts up with all this for more than two years, all the time seeking to preserve their bond.

Kallenbach’s ups and downs can be traced in an appointments and account book he kept for 1912 and 1913, which can be viewed in the archive of Gandhi’s Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad, India. For the sake of frugality and fitness, Kallenbach and Gandhi made a regular practice of walking the twenty-one miles from the farm, near a rail stop called Lawley, to the center of Johannesburg, following a route across a great expanse of veldt that much later, in the apartheid era, was turned into the sprawling black township of Soweto. On each occasion, Kallenbach records the times. When he walks with Gandhi, often starting as early as 4:00 a.m., it takes a little more than five and a half hours to reach their respective offices in the center of Johannesburg; on his own, he usually manages to lop an hour off. On every single mention, Gandhi in these pages isn’t Upper House but “Mr. Gandhi.” The formality seems to acknowledge that their relationship, however it’s understood, isn’t one of equals.

Today Lawley still functions as a rail stop. Next to it sprawls a large postapartheid shantytown of corrugated metal and mud huts squeezed together on virtually every square foot of some long-defunct white farm. When an attempt was made to restore Tolstoy Farm and erect a memorial there, the squatters from the shantytown soon stripped the place bare. When I visited it in 2008 there was not even a sign. All that was left were some banked brick benches, the foundation of an old farmhouse, the well-fenced dwellings of a few white stakeholders who work at an adjacent brick kiln, some burned-over eucalyptus trees, and a few fruit trees, progeny perhaps of the scores Kallenbach planted a century ago, and, finally, a view across the townships and mining slime dams to a Johannesburg Gandhi would scarcely recognize.

In their day, Gandhi and Kallenbach continued to experiment with diet, limiting their daily intake at one stage to a single carefully rationed evening meal. And every month or so Kallenbach recorded another “long discussion” with Mr. Gandhi. Details are completely absent, but sometimes these conversations provoke resolutions on Kallenbach’s side to step up his Hindi studies and come to a decision on leaving his profession. Then someone else comes into the picture, competing for his soul

mate’s attention, and a fresh shower of doubts rains down on him. The most personal and intriguing note in the diary is recorded on August 27, 1913, eight months after Gandhi has finally moved back to Phoenix. Tolstoy Farm has been wound up, Kallenbach is back at Mountain View, and Gandhi, on a visit, is staying with him. Then another of the Jews in Gandhi’s Johannesburg circle,

Sonja Schlesin, his feisty secretary, shows up. By some accounts, it was Kallenbach who introduced Schlesin, seventeen years his junior, to Gandhi in 1905; their families had been close in the old country. But he has come to consider her high-handed in her claims on Gandhi’s time and, in some sense, to view her as a rival. “On account of Miss Schlesin’s coming to Mountain View walked alone to office,” Kallenbach writes. “Discussions about her brought about Mr. Gandhi’s vow. It has been an exceedingly trying day for me.”

If this entry were an ancient cuneiform inscription, it would hardly be more difficult to decipher. Is he alluding to Gandhi’s vow of brahmacharya, or the recent vow that led to a fast the previous month over some carnal doings that surfaced at Phoenix? (

In Gandhi’s mind, there could be no such thing as innocent sexual play; earlier he’d complained about a case of “excessive tickling” at Phoenix.) Neither of those vows seems to be what Kallenbach has in mind. Probably he’s referring to a vow known only to K. and G. The context is obscure, but Kallenbach’s feelings, for once, leap off the page. Rivalries and jealousies of this sort would become chronic in Gandhi’s entourage in later years. But Kallenbach is special. In leaving Joburg, Gandhi appears to have left him behind, to have broken free. In fact, he made the move at the start of 1913 on the assumption that his dearest friend would eventually follow. Recognizing that Kallenbach is “on the fence,” he asks him in a tone that’s at once wheedling and passive-aggressive “to consider the joint life as we have lived it.” But the clearest clue to his feelings is this: in packing up his own things for shipment to Phoenix, it turns out, he has also packed and shipped Kallenbach’s books and tools.

Upper House is wounded when Lower House requests their return; even then he doesn’t give up. As we will see, this isn’t the end. Kallenbach eventually plunges into Gandhi’s last and greatest satyagraha campaign in South Africa, then seems to pull back again, thrown off balance by Gandhi’s newfound fondness for a British clergyman,

Charles F. Andrews. “

Though I love and almost adore Andrews so,” Gandhi writes, “I would not exchange you for him. You still remain the dearest and nearest to me … I know that in my lonely journey through the world, you will be the last (if

even that) to say good-bye to me. What right had I to expect so much from you!”

So much of what, we’re left to wonder. The answers can only be love, devotion, unquestioning support. In Gandhi’s words, Kallenbach was “

a man of strong feelings, wide sympathies and childlike simplicity.” On another occasion, he complained of his friend’s “

morbid sensitiveness,” meaning, it seems, his jealousy and susceptibility to other influences. Three months before he leaves South Africa, Gandhi again reassures his Jewish soul mate: “You will always be you and you alone to me. I have told you you will have to desert me and not I you.” Finally Kallenbach succumbs. He sails with Gandhi when he leaves the country with the intention, soon thwarted, of accompanying him all the way to India.

The several ties that bound Gandhi to the Transvaal—the satyagraha campaign, Tolstoy Farm, and Kallenbach—cannot easily be disentangled. But by January 9, 1913—the day Kallenbach jotted in his diary, “Mr. Gandhi and balance of Tolstoy Farm occupants left for Phoenix”—the strongest of these was the personal one to the architect. Only when it’s factored into consideration can Gandhi’s prolonged abstention from Indian politics in Natal be plausibly explained.

The timing of

Gandhi’s departure from the Transvaal and his return to Phoenix had little or nothing to do with Indian politics in Natal, from which he’d been conspicuously removed for a decade. It was dictated by a pledge that his staunch admirer and presumptive guru, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, had wrung from him at the end of his triumphal five-week tour of South Africa in 1912. The Indian leader’s visit, organized with all the pomp and circumstance usually reserved in South Africa for visits by British cabinet ministers—a blur of public tributes, crowded procession routes, and civic receptions attended by dignitaries who in that era were, by definition, nearly all white—had brought Gandhi out of his retreat at Tolstoy Farm. At its end, when Gokhale sailed for home, Gandhi and Kallenbach accompanied him as far as Zanzibar. When Indian communities at East African ports along the way turned out to welcome the leaders, they found the lawyer from Johannesburg in Indian garb for the first time in southern Africa since the London-returned dandy wore a turban into a

Durban courtroom, the day after he arrived from India, now nearly twenty years earlier. The older man (“

whose eyes were always on me,” so Gandhi later wrote) used the time on board to talk

earnest politics. “

In these conversations Gokhale prepared me for India,” Gandhi said. When they parted in Zanzibar, Gokhale exhorted, all but commanded, Gandhi to prepare to put South Africa behind him within a year and come home to fulfill his destiny. Gandhi, it appears, promised to try. Back at Tolstoy Farm by mid-December 1912, it took him just four weeks to wind up that particular experiment with truth and move his base back to Phoenix. In his own mind, this was just the start of a longer eastward journey that had always been inevitable. “

I shall be there when the time comes,” he’d written when the subject of his repatriation came up. His “inner voice,” it seemed, would help him know when his “withdrawal,” as he termed it in a letter to Kallenbach, should occur.

There was unfinished business he still needed to clear. Gandhi believed he’d reached a compromise with Smuts in early 1911 that would enable him to write finis to the

satyagraha campaign that had been his ostensible reason for camping in the Transvaal. That was a year after South Africa’s first national government—all white, of course—had come into being. In truth, the compromise Gandhi had been ready to embrace would have made only a slight difference in the real circumstances of beleaguered Indian communities. The “Black Act” requiring Indian registration in the Transvaal would have been repealed by the new white Parliament (for whatever that was worth, now that practically all Indians had registered), and an immigration law that was explicitly anti-Asian would have been replaced by one that was seemingly nonracial in terminology, only implicitly and functionally anti-Asian. (By means, for instance, of literacy tests in European languages, with Yiddish being included on the list of languages in which an immigrant could be tested but not, of course, Hindi, Tamil, or any other Indian language.) Absurdly, as a gesture to the principle of equality, it would retain the provision from earlier drafts that six “educated” Indians (meaning Indians who’d followed an English curriculum) could be admitted to the Transvaal annually, a way around the likelihood that even Indians who were proficient by Western standards would still be effectively barred.

Seen in a broader context, as a second generation of Indians born in South Africa was beginning to do, the “compromise” didn’t promise much. If it went through, Indians would still lack a vote; their rights to own land or open businesses could still be subject to severe restrictions; the indentured labor system would be left standing; and educational opportunities for Indian children would remain entirely at the discretion of antagonistic white authorities. Still, for a few months in 1911, there

seemed to be a deal. Then the government introduced bills supposed to embody the extremely limited aims of the Gandhi-Smuts bargain, and once the arcane language and obscure cross-references to provisions in other laws had been parsed, traced, and decoded, the only thing that was obvious was that Gandhi’s good faith had yet again been exploited. What one provision appeared to grant, another provision took away. If anything, the draft legislation worsened conditions for Indian residents and raised the barrier to immigration even higher.

Threatening renewed resistance, Gandhi himself had now to acknowledge that the immigration reform over which he’d bargained had yielded a new “Asiatic Expulsion Bill.” New drafts were then promised, withdrawn, and promised again as the authorities waited him out, testing Indian resolve. Nearly five years after the start of satyagraha, he had nothing to show for the resistance his leadership had inspired. Indians had courted arrest and gone to jail more than two thousand times, serving sentences of up to six months at hard labor; some, like

Thambi Naidoo and Gandhi’s son Harilal, doing so repeatedly.

Hundreds of other resisters had been deported back to India. The world had fleetingly taken notice—India, especially—but the new white government had outmaneuvered Gandhi. Disillusion was building, especially in the Natal to which he returned at the start of 1913.

Then he did something remarkable, upping the ante. He added a new demand and put it at the top of his list, one that had more heft, that spoke directly and clearly to the central question of whether the Indian community in South Africa was to be regarded as temporary or permanent, a demand that carried radical implications, bearing as it did on the prospects of the poorest Indians, the indentured laborers of Natal who toiled in a system Gandhi had long since identified as “

a substitute for slavery.” Seemingly all of a sudden, Gandhi made the abolition of Natal’s annual three-pound head tax on former indentured laborers the main object of the new satyagraha campaign he’d been threatening for two years.