Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India (50 page)

Read Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India Online

Authors: Joseph Lelyveld

Tags: #Political, #General, #Historical, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #Biography, #South Africa - Politics and government - 1836-1909, #Nationalists - India, #Political Science, #South Africa, #India, #Modern, #Asia, #India & South Asia, #India - Politics and government - 1919-1947, #Nationalists, #Gandhi, #Statesmen - India, #Statesmen

In September 1939, in the immediate aftermath of the declaration, the Congress rejects a resolution Gandhi drafted.

It’s the first time in twenty years this has happened; he views it as a “conclusive defeat.” The

spurned draft promised support of the British war effort by all available nonviolent means. Instead, the Congress sets up a bargaining situation, making its promise of support conditional on a British commitment on independence. Implying the bargain it imagines, it soft-pedals Gandhi’s emphasis on nonviolence.

Ten months later, in June 1940, it formally votes at Gandhi’s request “to absolve him from responsibility for the program and activity which the Congress has to pursue” in order to free him “to pursue his great ideal in his own way.” Three months later, after the viceroy has brushed off its demand for a commitment on Indian freedom, it summons Gandhi back to leadership. In December 1941 he’s out again, over disagreements about the use of force. A mere two weeks later, he’s back on his own terms, only now his terms have started to undergo a subtle shift. Eventually, he makes a reluctant concession: if India is declared independent during the war, he acknowledges, it will probably conclude it needs armed forces; he also agrees that Allied forces could continue to use its territory as a base from which to bomb

Japanese positions in Burma and fly arms over the hump to

China. These adjustments in his and the Congress’s position come painfully, over many months. They’ve no effect. The British still aren’t biting:

Winston Churchill, the “die-hard” imperialist, would famously assert that he hadn’t become prime minister to preside over the empire’s dissolution. Having failed so far to dislodge or even budge the Raj, Gandhi and the Congress prepare for the largest campaign of noncooperation and nonviolent resistance in twelve years, since the Salt March, serving an ultimatum on the British: hand over sovereignty or face the consequences. In 1942, at the height of the Japanese advance across Asia, against the better judgment of Nehru, who took the threat of an invasion seriously, “Quit India!” becomes their cry.

Through all his ins and outs, Gandhi has now moved over three years from unconditional support for the war effort by all available nonviolent means to a threat of nonviolent resistance on a massive scale unless India is freed to make “common cause” with the Allies in ways that wouldn’t necessarily be nonviolent.

On August 8, 1942, the Congress endorses the “Quit India” resolution, which promises that a free India will “resist aggression with all the armed as well as nonviolent forces at its command.” That phrase embodies Gandhi’s tacit shift on the question of armed force, his willingness to align himself with Nehru and other Congress leaders. Now he’s ready to go full tilt. The coming campaign will be, he promises, “

the biggest struggle of my life.” Here we’ve a flash of the fully possessed, “do or die” Gandhi, the fervent commander, who led

indentured miners into the Transvaal in 1913, who later promised “swaraj in a year,” who subsequently marched to the sea to harvest a handful of salt. But the morning after the vote on the “Quit India” resolution he’s arrested again in Bombay and taken as a prisoner to the Aga Khan Palace outside Poona, where he’s sidelined for the next twenty-one months until the British, alarmed by his high blood pressure, decide to let him go in order not to have to face an uproar over his dying in detention.

Churchill’s cabinet has discussed the idea of deporting Gandhi to Uganda but recognizes finally that its American ally, not to mention the masses of India, might find this hard to swallow. Gandhi’s last campaign hadn’t achieved anything like his standard of nonviolent discipline. “

Mob violence remains rampant over large tracts of the countryside,” the viceroy reported to Churchill three weeks after his arrest. By the end of the year, nearly one thousand persons had been killed in clashes with the police; some sixty thousand arrested in the British crackdown on the Congress. Egged on by Churchill, the British searched for evidence that Gandhi, though jailed, had been complicit in this violence, perhaps conspiring with the

Japanese. They never found it, but Gandhi’s own words before his arrest seemed to hint that he wouldn’t be surprised by a surge in rioting.

Indian nonviolence had always been imperfect, “limited in both numbers and quality,” he coolly told an American correspondent—that is, in the availability of trained satyagrahis who could be relied on to make the requisite self-sacrifice—but “it has infused life into the people which was absent before.” He isn’t threatening or justifying violence, but assuming for the moment the position of a detached observer, a realist, he seems to be suggesting that this time it couldn’t be ruled out. This Gandhi sounds like the pre-Mahatma of 1913 who warned the South African authorities he might lose control of his movement.

Gandhi’s moral stubbornness, ascribed by the Mahatma to the dictates of his “inner voice,” seems to function in his later years like a suddenly released spring or coil, distancing him from responsibility for far-reaching political decisions. The pattern had been set by the time his last imprisonment ended on May 6, 1944. But Nehru and Patel, the whole Congress Working Committee, remained in jail; the viceroy rebuffed his request to consult them. So, for the next thirteen months, until their release, only he could act on national issues. His most significant venture in that time was an attempt to bridge the widening chasm between the

Indian National Congress and the Muslims—in particular, a resurgent

Muslim League under its self-styled Quaid-i-Azam, or “great leader,” Mohammed Ali Jinnah.

This was the same Jinnah who’d welcomed him to India nearly three decades earlier with a heartfelt plea for national unity; the nationalist whom Gokhale, Gandhi’s sponsor and guru, had earlier hailed as an “ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity”; who in 1916 lived up to that tribute by cementing an accord between the Congress and the Muslim League that seemed a breakthrough at the time; the same Jinnah, fastidious lawyer that he was, whose belief in constitutional methods had then been so ruffled, so offended, by Gandhi’s introduction of mass agitation based on appeals to religious themes (of Muslims as well as Hindus) that he’d walked away from the Congress; the political broker who was, nevertheless, still trying as late as 1928 to find common ground between the two movements on the constitutional shape of an independent India; and who in 1937 offered to enter coalitions with new Congress governments at the provincial level, only to be rebuffed.

He was the same man but no longer the same nationalist. Returning from his four-year exile in England, he paid Gandhi the implicit compliment of imitation. Mass agitation based on religion no longer offended him; it was, he’d learned, the surest path to national leadership. Now he argued that there’d never been and never could be an Indian nation, only Hindu India (Hindustan) and Muslim India (Pakistan)—two equal nations, no matter that one outnumbered the other by better than two to one (roughly three to one if untouchables were counted as Hindus). By Jinnah’s reasoning, if Muslims were a nation, they weren’t a minority, whatever the population tables showed; any negotiations, he insisted, had to be on that basis. The Quaid’s sartorial transformation wasn’t as drastic as the Mahatma’s, but in place of his smart, custom-tailored double-breasted suits he now sometimes appeared in the long traditional, buttoned-up coat known as a

sherwani

and the rimless cap fashioned from sheep hide that learned Muslims called maulanas favored; henceforth it would sometimes be described as a Jinnah cap, worn in contrast to the white khadi caps donned by congressmen that were everywhere known as

Gandhi caps. With skill and considerable cunning, the Quaid had set himself up to be Gandhi’s foil.

There’d never been much warmth between these two Gujarati lawyers, but Gandhi, who’d always treated Jinnah with respect and had reached out to him at times when Nehru and most other Congress leaders tended to write him off, now made a point of referring to him as

Quaid-i-Azam. (

In 1942, days before the launch of the “Quit India” campaign, he’d even suggested that Jinnah could form a government if the British weren’t ready to hand over power to the Congress.) For his part, Jinnah had always made a point of referring to him frostily as “Mr. Gandhi,” conspicuously shunning any use of his spiritual honorific. But now the Quaid unbent sufficiently, on one occasion at least, to call him Mahatma. “

Give your blessings to me and Mahatma Gandhi so that we might arrive at a settlement,” he asked a throng of Muslim Leaguers in Lahore as the day of their summit neared. These small glimmers of regard were enough to make the British worry that the two leaders might form an anticolonial front in the midst of the war.

Hindu nationalists worried as well. A mob showed up at Wardha with the intention of physically blocking Gandhi’s way when it was time for him to leave for the station to board his train for Bombay to meet Jinnah. Their idea, then as now, was to protest any move to alienate any piece of the “motherland.” Prominent in the crowd was a high-strung Brahman editor named

Nathuram Godse who several years later, after India’s partition, would step forward as the gunman Gandhi had long anticipated.

When the leaders finally faced each other in the study of Jinnah’s residence on Mount Pleasant Road in the upscale Malabar Hill section of Bombay on September 9, 1944, in the first of what would be a marathon of fourteen sessions over eighteen days, Jinnah asked for Gandhi’s credentials. “

I thought you had come here as a Hindu, as a representative of the Hindu Congress,” he said archly, according to Gandhi’s version of the exchange, fully aware that this formulation would grate on his guest. “No, I have come here neither as a Hindu nor as a representative of the Congress,” Gandhi replied. “I have come here as an individual.” In that case, his host wanted to know, if they reached an accord, who would “deliver the goods”?

It was a barbed but reasonable question. Setting aside his openly eclectic, nonsectarian approach to religion, not to mention his decades-long quest for “unity,” Gandhi had tacitly accepted the idea of a separate Muslim state as a basis for negotiation.

Not only had the Congress already voted down the set of proposals he now advanced for discussion; it had done so with his approval. If he was reversing himself, Jinnah wanted to know, who would follow him? Was he even serious? The Pakistan Gandhi was ready to support would enjoy a certain amount of autonomy within an Indian union, which might be a relatively loose federation in which defense and foreign affairs were handled as national concerns. If Pakistan could be kept within India, he allowed himself to

hope, “heart unity” might yet follow.

Putting it in writing at the start of the third week of talks, Gandhi went a step further, acknowledging a right of secession for the Muslim-majority areas that could lead to a

“Treaty of Separation” between “two sovereign independent states.”

That still wasn’t far enough for Jinnah. The Pakistan he had in mind had to start off as sovereign. It couldn’t trust a Hindu-dominated regime to draw its boundaries or see to the terms of its separation; only by its own free choice could it find itself inside an independent India. Thus its destiny and boundaries had to be determined before independence, not after, as Gandhi kept insisting. Immediately, it was apparent that they were discussing two different Pakistans, two different ideas, at least, of the bargaining power Jinnah would wield in any showdown. “

I am amazed at my own patience,” Gandhi said after a grueling first session, which lasted three and a quarter hours.

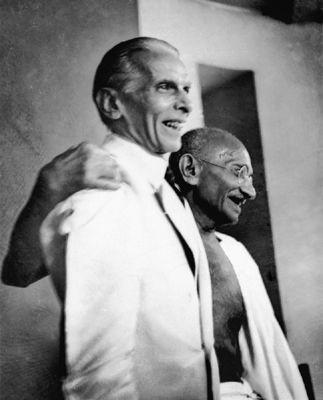

With Jinnah at the start of Malabar Hill talks, September 1944

(photo credit i11.2)

Godse, the assassin-to-be, and his fellow Hindu chauvinists needn’t have feared that Gandhi would embrace a shrunken Hindustan.

His aim, Gandhi remarked privately, while the talks were still going on, was to prove to Jinnah “from his own mouth that the whole of the Pakistan proposition is absurd.” His words here convict him of overconfidence.

The Quaid-i-Azam finally became convinced that a wily Gandhi was stringing him along. “

I have failed in my task of converting Mr. Gandhi,” he said. The “Mr.” could be read as a tip-off that the talks had failed.

Jinnah claimed that only the Muslim League could speak for British India’s ninety million Muslims and only he could speak for the Muslim League. Gandhi’s claim, though couched with infinitely more generosity and tact, was no less sweeping. “

Though I represent nobody but myself,” he wrote to Jinnah, “I aspire to represent all the inhabitants of India. For I realize in my own person their misery and degradation, which is their common lot, irrespective of class, caste or creed.”

Jinnah was so engrossed in the tactics of the moment that he may have outmaneuvered even himself by waiting so long to define his idea of a satisfactory Pakistan, putting it forever beyond reach. (

This is so, at least, if, as has sometimes been argued, his actual aim was to secure for Muslims a permanent share of power at the national level within India, rather than a separate state.) Gandhi, a master of the art of compromise, at least by his own estimate, may have been willing now to recognize a right of “self-determination” in Muslim-majority provinces and, therefore, a theoretical right of secession. But he was elusive on the central issue of power. Just as in his bargaining with Ambedkar, he couldn’t contemplate any scaling back of his movement’s claims—or his own—to represent the whole of India. That was the difficulty with “truth” as a standard for political judgment: it lacked flexibility. Neither the Quaid-i-Azam nor the Mahatma was a completely independent actor. Jinnah had to take care not to shatter the expectations he’d aroused in Muslim-minority provinces that could never be part of any conceivable Pakistan. Gandhi couldn’t ignore the rising specter of Hindu militancy. Each needed an act of faith from the other that was next to impossible now that Jinnah had given up on Indian nationalism.