Haiti After the Earthquake

Read Haiti After the Earthquake Online

Authors: Paul Farmer

Table of Contents

Â

Â

Â

To Al and Diane Kaneb,

and all those who stand with the Haitian people

and all those who stand with the Haitian people

Then Jesus cried out again in a loud voice and breathed his last.

At that moment, the curtain of the temple was torn in two,

from top to bottom. The earth quaked, and the rocks were split.

The centurions and those with him who were keeping watch of Jesus,

saw the earthquake and what took place and they were terrified ...

At that moment, the curtain of the temple was torn in two,

from top to bottom. The earth quaked, and the rocks were split.

The centurions and those with him who were keeping watch of Jesus,

saw the earthquake and what took place and they were terrified ...

âMatthew 27:50â52, 54,

Palm Sunday Liturgy

Palm Sunday Liturgy

Â

Â

The dead are always looking down on us, they say.While we are putting on our shoes or making a sandwich,

they are looking down through the glass bottom boats of heaven

as they row themselves slowly through eternity.

Â

They watch the tops of our heads moving below on earth,and when we lie down in a field or on a couch,

drugged perhaps by the hum of a long afternoon,

they think we are looking back at them,

which makes them lift their oars and fall silent and wait,

like parents, for us to close our eyes.

â

The Dead,

Billy Collins

The Dead,

Billy Collins

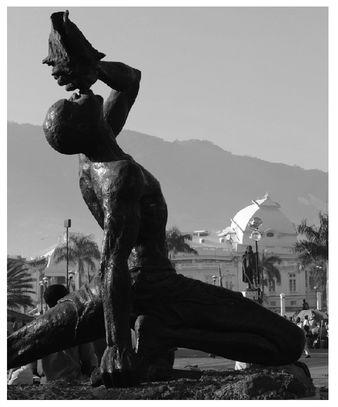

NÃG MAWON

H

aiti was founded

by a righteous revolution in 1804 and became the first black republic. It was the first country to break the chains of slavery, the first to force Emperor Napoleon to retreat, and the only to aid Simón BolÃvar in his struggle to liberate the indigenous people and slaves of Latin America from their colonial oppressors. Tragically, this history of liberty and self-determination has drawn two centuries of political and economic ire from powerful countries resulting in policies which have served to impoverish the people of Haiti.

aiti was founded

by a righteous revolution in 1804 and became the first black republic. It was the first country to break the chains of slavery, the first to force Emperor Napoleon to retreat, and the only to aid Simón BolÃvar in his struggle to liberate the indigenous people and slaves of Latin America from their colonial oppressors. Tragically, this history of liberty and self-determination has drawn two centuries of political and economic ire from powerful countries resulting in policies which have served to impoverish the people of Haiti.

Feared by Thomas Jefferson for their successful uprising; extorted by France in 1825 for 150 million francs to compensate the loss of the

Empire's “property”âboth slaves and landâ(a debt the Haitian people completed paying, with interest, more than a century later); occupied by the U.S. military between 1915 and 1934 to stifle European influence in the Western Hemisphere; and disrespected in their quest for democracy by an unrelenting series of dictators and coup d'états backed by Western countries: the free people of Haiti have been continually re-shackled politically and economically.

Empire's “property”âboth slaves and landâ(a debt the Haitian people completed paying, with interest, more than a century later); occupied by the U.S. military between 1915 and 1934 to stifle European influence in the Western Hemisphere; and disrespected in their quest for democracy by an unrelenting series of dictators and coup d'états backed by Western countries: the free people of Haiti have been continually re-shackled politically and economically.

In the wake of the January 12, 2010, earthquake, Haiti's history of unrelenting struggle for justice is its greatest resource. This history, as Haitians remind us, is what makes Haiti mighty: mighty without material wealth, without natural resources, without arable land, without arms.

Amidst the rubble of the houses, buildings, and schools, and in front of the once grand National Palace, stands Nèg Mawonâthe symbol of Haiti. Nèg Mawon at once embodies the marooned man, the runaway slave, and the free man. He symbolizes the complex history of the Haitian people: stolen from Africa, marooned on an island and liberated through a brave and radical revolution. Shackles broken, machete in hand, the free man does not hide; rather he blows a conch to gather others to fight for the freedom and dignity of all people. For the self-evident truthâthat all men are created equal. Nèg Mawon is the indefatigable spirit of Haiti's people, a people profoundly and proudly woven to their history.

When I arrived in Haiti on Thursday, January 14, 2010, I asked my friend who was driving, “Koté Nèg Mawon”âwhere is the free man? “Li la” he saidâhe is here. And as we rounded the corner behind Champs Mars, the plaza in front of the devastated palace where thousands had already made their homesâand remain todayâthere, rising from the dust of the still trembling earth, stood the statue of Nèg Mawon. I was drawn by the image out of the car and as I stood, weeping, an old woman put her arm around me; she too was crying. I said, “Nèg Mawon toujou kanpé!!”âthe free man is still standing!! And she replied, powerfully, “Cheri, Nèg Mawon p'ap

jamn

kraz̩Ӊmy dear, the free man will

never

be broken. It is with this surety that we must stand with Haiti, a country whose spirit and people will never be broken, and work in solidarity toward the future the Haitian people deserve.

jamn

kraz̩Ӊmy dear, the free man will

never

be broken. It is with this surety that we must stand with Haiti, a country whose spirit and people will never be broken, and work in solidarity toward the future the Haitian people deserve.

âJoia S. Mukherjee

Haiti

after the earthquake

WRITING ABOUT SUFFERING

S

ome years ago,

after two decades of witnessing and writing about epidemic disease and violence of all types, I set out to write a book based on some lectures about violence and medicine that I'd given at the University of Rochester. The title of the book was going to be

Swords of Sorrow

, from a Gospel line (Luke 2:35): Mary learns that her soul will be pierced by a “sword of sorrow” because she is willing to be a vessel of grace. I liked the alliteration. But I never finished that book. What was the point, I worried, of writing another book about the suffering caused by war and genocide and other misfortunes natural and unnatural?

ome years ago,

after two decades of witnessing and writing about epidemic disease and violence of all types, I set out to write a book based on some lectures about violence and medicine that I'd given at the University of Rochester. The title of the book was going to be

Swords of Sorrow

, from a Gospel line (Luke 2:35): Mary learns that her soul will be pierced by a “sword of sorrow” because she is willing to be a vessel of grace. I liked the alliteration. But I never finished that book. What was the point, I worried, of writing another book about the suffering caused by war and genocide and other misfortunes natural and unnatural?

I thought again about that truncated project shortly after an earthquake struck Haiti's capital city on January 12, 2010. Preliminary estimates of the dead ran to six figures. The immediacy of rescue and relief soon gave way to a series of questions about the dimensions of what had happened, about why Haiti had been particularly vulnerable to such a disaster, and about how to respond to the unfolding “humanitarian crisis” (to use the jargon of the day). Suffering is never just pure suffering; it occurs in a particular place and time. My book would have examined histories of suffering in Haiti, Guatemala, and RwandaâHaiti being the place that has taught me the most.

Knowledge of Haiti might not help a trauma surgeon attend to broken bodies pulled from the rubble. But deep familiarity with the place helped frame answers to some of the questions posed above

and also helped guide actions in the aftermath of the quake and during the reconstruction that would follow. The relevant knowledge needed to be historically deep (because the damage caused by the quake and the responses to it were rooted in Haitian history) and geographically broad (because Haiti had for centuries been caught up in a transnational economic and political web, a condition very much on display before and after the quake). This may sound academic. I didn't want to write a dispassionate study of the Haitian earthquake. Instead, I wanted to offer an account of a difficult time; to bear witness.

and also helped guide actions in the aftermath of the quake and during the reconstruction that would follow. The relevant knowledge needed to be historically deep (because the damage caused by the quake and the responses to it were rooted in Haitian history) and geographically broad (because Haiti had for centuries been caught up in a transnational economic and political web, a condition very much on display before and after the quake). This may sound academic. I didn't want to write a dispassionate study of the Haitian earthquake. Instead, I wanted to offer an account of a difficult time; to bear witness.

Bearing witness surely has a certain value, especially if it is linked to goodwill efforts to prevent unnecessary suffering caused by war or disease or insufficient preparation for natural disasters. Documentation by eyewitnesses can serve to inform people who are not on the scene but are in a position to help or hinder subsequent interventions. But was it appropriate for a physician, an American at that, to speak for the victims? Many in academia would argue vehemently that only the victims could speak for themselves, and that anyone who presumed to speak on their behalf would rob them of their agency. However, this is not always true: as far as the earthquake goes, the chief victims' voices were stilled forever. Seeking to “echo and amplify” (to paraphrase Haiti's former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide) the voices of those we encountered as well as those silenced was and remains our principal interest in writing about violence of all sorts.

I use

we

and

our

here because, a few months after the quake, a small group of friends and coworkers decided to put together an account of that terrible time. We've done our best to offer an honest rendering, even though no one had stopped to take notes amidst the maelstrom. It is also our desire to broadcast the voices of those most affected.

we

and

our

here because, a few months after the quake, a small group of friends and coworkers decided to put together an account of that terrible time. We've done our best to offer an honest rendering, even though no one had stopped to take notes amidst the maelstrom. It is also our desire to broadcast the voices of those most affected.

This book faces the same problems I encountered in writing

Swords of Sorrow

. In addition to clichéd (and overly academic) concerns about voice and representation, serious challenges are involved in seeking to write and complete a book in a few months. These challenges are heightened by publishing such a book in English because

the primary victims of the quake do not speak English (or speak it less well than they do other languages).

Swords of Sorrow

. In addition to clichéd (and overly academic) concerns about voice and representation, serious challenges are involved in seeking to write and complete a book in a few months. These challenges are heightened by publishing such a book in English because

the primary victims of the quake do not speak English (or speak it less well than they do other languages).

We've tried to address these challenges in the structure of this book, which includes my own account along with a series of brief essays, photographs, and one drawing by friends, family, and coworkers. I describe the aftermath of the earthquake as experienced by a physician working alongside colleagues in Port-au-Prince and central Haiti both immediately after the quake and in subsequent months. I double back to revisit my personal history in Haiti, and that of Partners In Health and its Haitian sister organization, Zanmi Lasante, over the past twenty-five years.

Other books

Ultimate Love by Cara Holloway

Pain of Death by Adam Creed

Chained Cargo by Lesley Owen

Beguiled by Shannon Drake

Cattle Baron: Nanny Needed by Margaret Way

Monkey Play by Alyssa Satin Capucilli

The Undead Hordes of Kan-Gul by Jon F. Merz

Cecilia Grant - [Blackshear Family 03] by A Woman Entangled