Hands of My Father: A Hearing Boy, His Deaf Parents, and the Language of Love (14 page)

Read Hands of My Father: A Hearing Boy, His Deaf Parents, and the Language of Love Online

Authors: Myron Uhlberg

“We’re going fishing,” my father signed one day, his fingers flapping back and forth like a salmon swimming upstream.

It was my birthday, and he presented me with a bamboo fishing pole as my present.

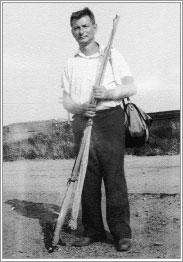

My father with fishing gear: looking for the Big One

A fishing pole? In Brooklyn?

Placing it reverentially in my small hands, his hands met my skepticism with a command: “Practice!”

Practice? In Brooklyn?

For a week I hung my new fishing pole out my third-floor bedroom window, practicing my casting. When I had my cast down well, I dropped the hook outside Mrs. Abromovitz’s kitchen window, one floor below. I had baited it with a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. I pretended she was a tuna. I had read somewhere that tuna like peanut butter and jelly. But Mrs. Abromovitz didn’t bite.

I had better luck trolling for the various pieces of clothing, including bloomers that looked like white blimps, strung out on the clothesline that stretched across the alley from her kitchen window to her bathroom window.

I got very good at hooking her brassieres. They were enormous contraptions. Attached by wooden clothespins, they hung down from their sagging straps like two baseball catcher’s mitts.

Early one morning my father woke me. Still sleepy, holding his hand, I walked with him to the subway train that would take us to Sheepshead Bay. The bouncing of the train and the screeching wheels did not wake me as I slept, head in my father’s lap. We arrived at our stop with a jolt, bouncing me awake.

My father held my hand as we walked toward the ocean, which I could smell but couldn’t yet see.

In the darkness we came to the end of Brooklyn and walked up a ramp onto a boat that bobbed up and down, while rocking back and forth at the same time. This could be trouble, I thought.

My father placed my hands on the iron rail and held my shoulders. Feeling his hands holding me in the dark, I was not afraid.

As the sky began to lighten, the engine roared to life, with a puttering cough and the stink of gasoline, and the boat churned away from the dock in a cloud of black exhaust, heading out to sea. Suddenly the sun popped up at the edge of the ocean like a silhouette at a Coney Island shooting gallery, and I could see our wake stretching far behind, all the way back to Brooklyn. Seagulls followed, yelling down at us, “We’re hungry. What’s for lunch?” Boy, were they ever going to be disappointed when we caught all their food.

The boat stopped, and the captain dropped the anchor. As the sky began to brighten on the horizon, my father breathed deeply of the salt air, turned to me, and said, “Let’s catch a fish for dinner. A big one!”

I baited my hook. We fished all morning. We caught nothing. After a quick lunch we dropped our baited hooks back into the sea. We fished some more, all that afternoon, with the same result. We caught no fish.

As the sun began to sink over New Jersey, and the light began to fade, our captain pulled up the anchor and pointed the boat back toward Brooklyn. My father’s hands never left the railing; they had nothing to say. But his face said it all.

On the way to the subway station to catch the train that would take us home, my father stopped and bought a fish. A very large fish.

“If you don’t say anything,” he signed, “neither will I.”

When we arrived at our apartment door, he put the fish, wrapped in newspaper, into my arms and rang the bell that activated a flashing light in our hallway and a lamp in our living room.

My mother and my brother were happy to see us.

“Hoo-ha-ha, my husband, Lou, and my son the fisherman,” she signed, and took the big dead fish to the kitchen. My mother always referred to my father as “my husband, Lou,” not “your father.”

She did this unconsciously. Her immediate world, her self-contained silent world, was her husband, Lou, and herself. They were the binary stars of their own silent cosmos. My brother and I were two close planets in tight orbit. I knew with all my being that she loved us, but we were different because we could hear. Their hearing parents and siblings were in orbits farther distant. As were neighbors, then fellow workers. And finally, like all the visible but distant stars in the universe, came the vast multitude of hearing people whom they could never possibly know.

“Your husband, Lou?” I would sometimes ask her, in my poor attempt at humor. “Who is

that

? Sounds like my father.”

My mother looked at me as if I had lost my mind. For my deaf mother, in the hierarchy of her emotions and allegiance,

her husband

came before

my father.

That night, after my mother with the care of a brain surgeon carefully removed every single bone for my brother (I was old enough to fend for myself), we ate the fish. My mother kept looking at me with every bite she took, a smile on her face. As for my brother, he acted as if I had caught a whale.

I felt a little guilty that they believed that I had caught the fish. But only a little. The fish was delicious, bones and all.

8

The Smell of Reading

O

nce a month, on a Saturday afternoon, as regular as clockwork, my father, with great ceremony, took my mother, my brother, and me to the local Chinese restaurant for lunch. Eating out was a very big deal in those tail-end days of the Depression; the economic benefits of America’s fighting a world war had not, as yet, trickled down to our corner of the world, our peaceful Brooklyn neighborhood.

We would dress up for this occasion, I in my newest R. and H. Macy’s suit, my brother in the latest fashion for small kids, my mother in her best dress, topped with her fox stole, and my father in his tweed suit. (“I look like a professor,” he always signed, meerschaum pipe smoldering away in one corner of his mouth. His model was Robert Donat in

Goodbye, Mr. Chips,

a movie he favored, even though he could never quite figure out what the actors were up to.)

Once my father had examined my brother and me for stray hairs, unnoticed stains, and scuffed shoe leather, we descended in the elevator to the ground floor. After a final careful look at each of us, my father pushed open the heavy ornate glass lobby door, and we exited, linked together in a line, my parents arm in arm at the center, I holding my father’s hand, my brother holding my mother’s hand, all heading toward Kings Highway. As we walked up our block, eyes straight ahead, we would be closely watched by every one of our neighbors, who behind my back made their unfailingly unchanged comments: “Considering they’re deaf-mutes, they dress well.” “See how nice the deafies dress their boys.” “The father’s a deaf-mute, but he has a good job.” “The dummies are taking their kids to the ‘Chinks.’”

This last was, sadly, an all-too-common term in our neighborhood, generally used by us Jews, the same people who were appalled when the Irish in the Red Hook section of Brooklyn called

them

“Yids.” And as if that were not irony enough, even to my young ears, these were the same people who publicly objected to the treatment the Chinese had experienced in Manchuria at the hands, and bayonets, of Japanese soldiers, who were of course known as “Japs.” Anyway, I reasoned, in some small though misguided attempt at rationalization, this circle of unthinking prejudice was large and inclusive; no one was immune. The Irish

and

the Jews called the Polish “Polacks” the Polish called the Italians “Wops” the Italians called the Irish “Micks” and the Irish called the Chinese “Chinks.” Thus the circle of casual discrimination was complete.

What the Chinese called all of us, I had no idea.

As for the neighbors’ use of the term “dummies,” I had heard it from an early age, but it seemed somehow worse to me than the ethnic epithets because those words were group names, whereas “dummy” was personal; it referred specifically to the only deaf people the neighbors knew, my father and my mother. Nonetheless I was numb, if only from constant exposure to it, and did not allow it to interfere with my enjoyment of our monthly family outing.

The Chinese restaurant was located on the ground floor of a row of connected two-story wooden buildings. The street-level spaces were all filled with shops: bakery, poultry, hardware, vegetable, pharmacy, barber, beauty, and of course the neighborhood candy store.

As far as I was concerned, the highlight of this eating-out ritual was the sight of my father conversing in broken gestures with our Chinese waiter, while he in turn responded in broken English. Both of them studiously navigated their way through the dense, food-stained menu, filled with columns of incomprehensible Chinese characters, alongside garbled English translations. The waiter screamed good-naturedly at my father the contents of the day’s specialty of the house, as if sheer volume alone could get my father to

hear

the description of that delicacy. My father would just as loudly

scream

his gestures of approval right back at the waiter. Their heads nodding in perfect smiling agreement during this astonishing performance, neither one of them had any idea what the other was saying.

As for me, what would otherwise have been a situation of stinging embarrassment was rendered funny, as the other diners were regulars and were quite used to this scene. It was clear to me that they were staring at our table not in disgust but in tolerant amusement. I would settle for that.

One Saturday we had our usual Chinese lunch, beginning with the specialty of the house (it was always the same, month after month), an inedible, bone-laden, soggy bleached white fish with the most amazing pair of bulging sightless eyes staring at me in mute accusation. This was followed by two choices from column A (always the same choices, month after month) and one from column B (ditto), washed down with an undrinkable, thinly colored green liquid filled with floating black flecks. The meal concluded, as it always did, with a fortune cookie, the message of which, much prized and heartily laughed over by my father and mother, made absolutely no sense to me, although I liked the taste of the cookie itself.

But this day there was a change in the ritual.

After a close study of the bill, minutely itemized but thoroughly incomprehensible except for the total cost, my father paid and then turned to me and signed, “You can read now. It’s time for you to get a library card.”

Above the Chinese restaurant was our local library. I had heard about this place from the older kids, but I had never set foot there, since you needed a library card to enter, as I had been told (warned) by the big kids. They said the place contained every book that had ever been printed in the whole world. I had no idea if this was true.

Every book?

Why, there must be hundreds of them, I thought. Having just learned to read really well, I was more than idly curious as to the truth of the matter:

every

book? But then, the older kids could not be trusted. Most everything they told us, every warning they solemnly uttered, turned out to be greatly overblown.