Hands of My Father: A Hearing Boy, His Deaf Parents, and the Language of Love (2 page)

Read Hands of My Father: A Hearing Boy, His Deaf Parents, and the Language of Love Online

Authors: Myron Uhlberg

To my friends in the Deaf education community, Michelle Gennaoui, Jennifer Storey, and Nancy Boone, who told me as I was writing this book that this was a story that should be told.

To my football coaches: Harry Ostro, at Lafayette High School; Irv Heller, at Brandeis University, and in loving memory of Benny Friedman, two-time college All-American, enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame, and the first athletic director and only football coach at Brandeis University, and his beloved assistant, Harry Stein. I met them as a boy, and they showed me the way to become a man.

To Cindy Bowman, for her friendship, uncritical support, and for showing me what real courage looks like.

To my Brooklyn friends Lenny Lefkowitz, Tommy La Spada, Vico Confino, and in memory, Sam Mark, whom I called incessantly when I was writing about our Brooklyn childhood, checking my memories against theirs.

To Larry Ohrbach and Robert Sax, dear friends who supported me every step of the way in the writing of this book. And special appreciation for the friendship and sound advice of my oldest of friends, Eva and Sam Beller, and George and Sally McGlinnen.

This memoir owes much to my uncle, Milton Wolff, who in the years before his death shared with me his memories—and regrets—about growing up with his deaf sister, Sarah.

To Susan Wolff, daughter of my uncle Milton Wolff, who shared her memories of her complicated father as well as those of our equally complicated grandmother, Celia; and to Jerry Posner, and David and Roberta Trager, who did the same for their parents, my father’s younger sisters; and in memory of my cousin, Irving Posner, who would tell me his stories about our grandparents, David and Rebecca.

To my children, Eric, Robin, and Ken, who loved their deaf grandparents, and of whom I am so proud; and to my granddaughters, Alex and Kelli, and my grandsons, Max and Miles, who will one day read this book, and understand.

I am especially grateful to my brother, Irwin, with whom I consulted throughout the writing of this memoir, for his willingness to share with me his memories as well as his deepest feelings about growing up with our deaf parents.

And, as always, to my amazing wife, Karen, my best friend, my first reader, and most trusted advisor in all things literary and otherwise, who at every turn in my life said, “Why not?” You read every chapter, and then, knowing and loving my parents as you did, you told me, with unfailing honesty, and in as few words as possible, whether I had done their story justice. For this, as well as for more than I can say, I am forever grateful to you.

Prologue

I

n the language of the deaf, the sign for

remember

begins with the sign for

know:

the fingertips of the right hand touch the forehead.

But merely to know is not enough, so the sign for

remain

follows: the thumbs of each hand touch and, in this joined position, move steadily forward, into the future. Thus a knowing that remains, never lost, forever: memory.

In my memory, what I remember most vividly are the hands of my father.

My father spoke with his hands. He was deaf. His voice was in his hands.

And his hands contained his memories.

1

The Sound of Silence

M

y first language was sign.

I was born shortly after midnight, July 1, 1933, my parents’ first child. Thus I had one tiny reluctant foot in the first half of that historically fateful year, and the other firmly planted in the second half. In a way my birth date, squarely astride the calendar year, was a metaphor for my subsequent life, one foot always being dragged back to the deaf world, the silent world of my father and of my mother, from whose womb I had just emerged, and the other trying to stride forward into the greater world of the hearing, to escape into the world destined to be my own.

Many years later I realized what a great expression of optimism it was for my father and mother, two deaf people, to decide to have a child at the absolute bottom of the Great Depression.

We lived in Brooklyn, near Coney Island, where on certain summer days, when the wind was blowing just right and our kitchen window was open and the shade drawn up on its roller, I could smell the briny odor of the ocean, layered with just the barest hint of mustard and grilled hot dogs (although that could have been my imagination).

Our apartment was four rooms on the third floor of a new red-brick building encrusted with bright orange fire escapes, which my father and mother had found by walking the neighborhood, and then negotiated for with the impatient hearing landlord all by themselves despite their respective parents’ objections that they “could not manage alone” as they were “deaf and handicapped” and “helpless” and would surely “be cheated.” They had just returned from their honeymoon, spent blissfully in Washington, D.C., planned to coincide with the silent, colorful explosion of the blossoming cherry trees, which my mother considered a propitious omen for the successful marriage of two deaf people.

Apartment 3A was the only home my father ever knew as a married man. Its four rooms were the place he lived with and loved his deaf wife, and raised his two hearing sons, and then left by ambulance one day forty-four years after arriving there, never to return.

O

ne day my father’s hands signed in sorrow and regret the story of how he had become deaf. This was a story he had pieced together from facts he had learned later in life from his younger sister, Rose, who in turn had heard it from their mother. (The fact that he had to learn the details of his own deafness from his younger hearing sister was a source of enduring resentment.)

My father told me he had been born in 1902, a normal hearing child, but at an early age had contracted spinal meningitis. His parents, David and Rebecca, newly arrived in America from Russia, living in an apartment in the Bronx, thought their baby would die.

My father’s fever ravaged his little body for over a week. Cold baths during the day and wet sheet–shrouded nights kept him alive. When his fever at last abated, he was deaf. My father would never again hear a sound in all the remaining years of his life. As an adult, he often questioned why it was that he had been singled out as the only member of his family to become deaf.

I, his hearing son, watched his hands sign his anguish: “

Not fair!

”

My father and his father could barely communicate with each other. Their entire shared vocabulary consisted of a few mimed signs:

eat, be quiet, sleep.

These were all command signs. They had no sign for love between them, and his father died without ever having had a single meaningful conversation with his firstborn child.

My father’s mother did have a sign for

love.

It was a homemade sign, and she would use it often. My father told me that his language with his mother was poor in quantity but rich in content. She communicated less through agreed-upon signs than through the luminosity that appeared in her eyes whenever she looked at him. That look was special and reserved for him alone.

Like their parents, my father’s siblings—his younger brother, Leon, and his two younger sisters, Rose and Millie—never learned a word of formal sign. They remained strangers to him his entire life. At my father’s graveside Leon screamed his name, as if, finally, his dead deaf brother had been granted the power to hear his name on his brother’s lips.

In 1910, when he was eight years old, my father’s parents sent him to live at the Fanwood School for the Deaf, a military-style school for deaf children. My father thought they had abandoned him because he was damaged. In his early days there he cried himself to sleep every night. But ever so slowly he came to realize that rather than having been abandoned, he had been rescued. For the first time in his life he was surrounded by children just like him, and he finally understood that he was not alone in this world.

However, the education he received at Fanwood was certainly a mixed blessing. There, as at most deaf schools at the time, deaf children were taught mainly by hearing teachers, whose goal was to teach them oral speech. The deaf are not mute; they have vocal cords and can speak. But since they cannot monitor the sound of their voice, teaching them intelligible speech is extraordinarily difficult. Although my father and his classmates tried to cooperate with their teachers, not one of them ever learned to speak well enough to be understood by the average hearing person.

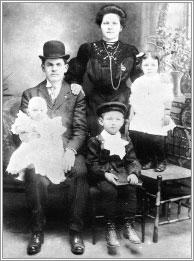

My father, his parents, his sister Rose, and his baby brother, Leon, circa 1907

While this futile and much-resented pedagogic exercise was being inflicted on the deaf children, sign language was strictly forbidden. The hearing teachers considered it to be a primitive method of communication suitable only for the unintelligent. Not until the 1960s would linguists decree ASL (American Sign Language) to be a legitimate language all its own. But long before then the deaf, among them the children at my father’s school, had come to that conclusion themselves. Every night, in the dormitory at Fanwood, the older deaf children taught the younger ones the visual language of sign.

With sign, the boundaries of my father’s silent mental universe disappeared, and in the resulting opening sign after new sign accumulated, expanding the closed space within his mind until it filled to bursting with joyous understanding.

“When I was a boy, I was sent to deaf school. I had no real signs,” my father signed to me, his hands moving, remembering. “I had only made-up home signs. These were like shadows on a wall. They had no real meaning. In deaf school I was hungry for sign. All were new for me. Sign was the food that fed me. Food for the eye. Food for the mind. Is wall owed each new sign to make it mine.”

My father’s need to communicate was insatiable and would cease only when the dormitory lights were turned out at night. Even then, my father told me, he would sign himself to sleep. Once asleep, my father claimed, he would dream in sign.

My father was taught the printing trade in deaf school, an ideal trade, it was thought, for a deaf man, as printing was a painfully loud business. The unspoken message transmitted to the deaf children of that time by their hearing teachers was that they were neither as smart nor as capable as hearing children. Thus they would primarily be taught manual skills, like printing, shoe repair, and house painting.