Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design (13 page)

Read Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design Online

Authors: Charles Montgomery

Driving to Unhappiness

The longer people choose to commute, the less happy they say they are with their entire life, suggesting that long-distance commuters are systematically failing to maximize utility.

(Graphic by Dan Planko, with data from Stutzer, Alois, and Bruno S. Frey, “Stress That Doesn’t Pay: The Commuting Paradox,”

Scandinavian Journal of Economics,

2008: 339–66.)

Intrinsic motivators, on the other hand, are about the journey rather than the destination. Their rewards come with those activities and states that relate to our deep need to feel connected to other people, to feel competent and effective, and to feel autonomous, or in charge of our actions. They contribute to the resilient kind of happiness that Carol Ryff wrapped up in her map of

eudaimonia

. And they are remarkably durable. Some good things we never get used to: playing sports, creative projects or hobbies, even doing work that requires concentration. When an activity is its own reward, it can actually feel better with every act of consumption. This is especially true in the social world. The more you see your friends, the more intimate and rich those friendships can become.

The problem is, we consistently make decisions that suggest we are not so good at distinguishing between ephemeral and lasting pleasures. We keep getting it wrong.

A Campus Conundrum

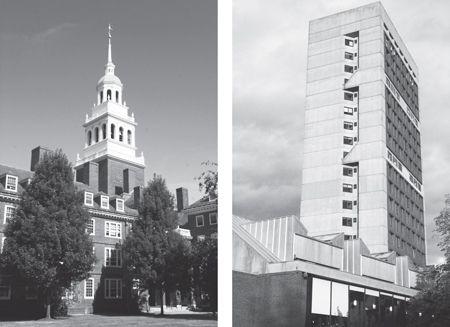

This flawed choice calculus is at work in all of us, including some of America’s brightest young minds. Consider the anxiety of the Harvard University dormitory resident. Near the end of their first year, freshmen at Harvard get the results of the lottery that determines where they will live for the rest of their undergraduate studies. This is considered a life-changing moment. After all, the lottery determines their home, their neighborhood, and, to some extent, their social life for the following three years.

Harvard’s dormitories vary wildly in their architecture, history, and social reputation. The most prestigious, Lowell House, with its grand redbrick facades, is a classic example of the Georgian Revival style. Its blue-capped bell tower is a local landmark, and its alumni include John Updike and Crown Princess Masako of Japan.

Harvard’s newest residences, built in the 1970s, lie on the far end of the status and architectural spectrum. The concrete tower of Mather House was described in

The Harvard Crimson

, the student newspaper, as a “riot-proof monstrosity designed by a prison architect,” although its bacchanalian soap-foam parties have achieved mythical status. (Noted alumnus: Conan O’Brien.)

News of a bad dormitory assignment is perceived as a psychic and social disaster. Elizabeth Dunn, now a psychologist at the University of British Columbia, endured the housing lottery in 1996, back when results were slipped under dormitory doors before dawn. Dunn recalls that some of her fellows actually performed mock prayers to “the housing gods” to deliver them from being assigned to the wrong house.

“All my friends wanted to be in Lowell House,” Dunn told me. “It’s so beautiful, it’s got that classic dining hall, squash courts in the basement, a wood-paneled library—it’s the image of the ideal Harvard life.”

When they ripped open their envelopes to discover their collective assignment to Lowell House, Dunn and her friends were overjoyed. They were convinced that the place had the power to make or break their happiness.

But were they right? After a couple of years of watching new freshmen go through the lottery—and studying psychology under Daniel Gilbert—Dunn wastn’t so sure. Under his guidance, she set out to find out.

First, she asked a fresh batch of freshmen to predict how happy they would be if assigned to each of Harvard’s twelve houses. Then she and a colleague interviewed those students after a year, and then again after two years in their new homes, to see how happy they actually were.

The results would surprise many Harvard freshmen. Students sent to what they were sure would be miserable houses ended up much happier than they had anticipated. And students who landed in the most desirable houses were less happy than they expected to be. Life in Lowell House was fine. But so was life in the reviled Mather House. Overall, Harvard’s choice dormitories just didn’t make anyone much happier than its spurned dormitories.

Why did the students get their happiness predictions so wrong? Dunn found a pattern that the students share with most of us: they put far too much weight on obvious differences between residences, such as location and architectural features, and far too little on things that were not so glaringly different, such as the sense of community and the quality of relationships they would develop in their dormitory. It wasn’t just architecture, history, or interior styling that made people happy. A good campus life was fueled by friendship and the social culture nurtured by longtime house masters and tutors. Mather House’s soap-foam parties may have had a more powerful cheering effect than Lowell’s stately dining hall.

The curious part was this: most students said that they knew that social life would be more important to their happiness than architecture, yet they still put greater weight on physical features. This is the standard mis-weighing of extrinsic and intrinsic values: we may tell each other that experiences are more important than things, but we constantly make choices as though we didn’t believe it.

Distracted by Aesthetics

Students thought they would be happier living in Harvard’s Lowell House (

left

) than they would be in Mather House (

right

). They were wrong.

(

Left

: Jon Chase/Harvard University;

right

: Kris Snibbe/Harvard University)

Lucky for them, the Harvard students were merely predicting their happiness. They weren’t actually able to choose their home. In the rest of the city, millions of people get the happiness calculus wrong, time and again, and have to live with the consequences for years.

Seeing Wrong, Measuring Wrong

Quick: Which would make you happier—living in California or the U.S. Midwest?

If you chose California, you are like most people—including midwesterners, who told surveyors they were sure that Californians were happier. Californians agreed. They were all wrong. Californians and midwesterners report pretty much the same level of life satisfaction.

How is it that most of us get this question wrong? Part of the answer lies in the way we frame decisions and in a cognitive quirk known as the focusing illusion. We tend to focus on one or two glaring differences between choices—things we can see or picture, such as weather—and we ignore or underrate less conspicuous but powerful details such as crime, commute times, social networks, and pollution. No matter how much more friendly and easy life might be in Ohio, what sticks in our heads is the vivid contrast between that mental image of sunshine and surf and one of dreary winters and roadside slush.

The sad part is that a place’s popularity can actually destroy the elements that contribute to happiness. The more we flock to high-status cities for the good life—money, opportunity, novelty—the more crowded, expensive, polluted, and congested those places become. The result? Surveys show that rich, high-status states in the United States are among the least happy in the country. Citizens of Canada’s big, high-status cities (such as Toronto and Vancouver, which consistently hover near the top of global quality-of-life lists) say they are much less satisfied with life than people living in small towns and humble backwaters such as Sherbrooke, Quebec, and Brantford, Ontario.

*

But we keep arriving, and in our collective pursuit we ensure that highly desired places are even less able to make us happy.

We are far less rational in our decisions than we sometimes like to believe. Now neuroscientists are starting to figure out the means by which our brains can turn a supposedly rational decision into a shouting match between logic and emotion.

The Corrupted Decision

David Halpern, an architect and occasional adviser to the British government, once conducted an experiment in which he had a group of volunteers rate the attractiveness of a series of images of human faces and buildings. Some of those volunteers were architecture students. Others were not. The volunteers generally all had the same response to the various human faces, but the longer any one of them had studied architecture, the more his or her taste in buildings diverged from that of the crowd. So while regular people feel delighted by the faux-Victorian facades of Disneyland’s Main Street U.S.A., most architects can’t stand the place. Instead they make pilgrimages to gaze at Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building, a black box in Manhattan whose aesthetic flourish consists of an almost-imperceptible exoskeleton of steel I beams.

Snobbery? Not necessarily. Architects’ brains may be physically altered by the act of studying and reading about the philosophy of building. Virginia Tech neurobiologist Ulrich Kirk and his colleagues used fMRI machines to see how the brains of architects and nonexperts would react to pictures of buildings. When a typical architect was asked to rate a building, her medial orbitofrontal cortex (a part of the brain that helps measure how much reward we’ll get from decisions) lit up much brighter than the same region in the nonexpert’s brain. The architect’s hippocampus, a sea horse–shaped instrument that works something like a librarian for all our memories, was also more fully activated.

Not to demean the profession of architecture, but researchers found similar results in the brains of people making that most mundane of choices: Coke or Pepsi. The mere sight of a can emblazoned with the Coke label activated volunteers’ hippocampi more than the act of actually sipping the cola, and this caused people to prefer its taste. (The Pepsi label had little effect.) The point here is that exposure to cultural information can change the way our brains function, dredging up images and feelings that alter the way we experience things.

*

With its complex structures and its billions of neurons, the brain works like a microcosm of human society. Just as the voices and actions of millions of people contribute to societal decisions, groups of neurons collaborate and compete for influence as the brain itself makes decisions.

“In the end, your decision depends on information propagation,” the neuroscientist Jan Lauwereyns told me. “Certain types of information gain the spotlight, like getting prime-time coverage on television, and this biases our decisions.”

Just as architects are biased by their scholarship, we all lug around a heavy bag of cultural messages. The hippocampus and other parts of the brain fight to give these messages a role in each decision, whether we realize it or not.

In the end, our evaluation of what is “good” can be entirely subjective. Our brains are pushed and pulled by the powerful synergy of memory, culture, and images. So our concept of the right house, car, or neighborhood might be as much a result of happy moments from our past or images that flood us in popular media as of any rational analysis of how these elements will influence the moments of our lives.

Given the images that the contemporary city dweller’s hippocampus has filed away, this information storm can easily lead to unreasonable expectations. Consider a little girl’s first dream home: the dollhouse. When the toy manufacturer Mattel held a contest to create a new home for their iconic Barbie toy in 2011, the winning design was the equivalent of a 4,880-square-foot glass mansion on three acres. Estimated construction cost in real life: $3.5 million. As sure as that house was pink, its dimensions will be transposed onto the aspirations of a generation of girls who grow up playing with it.

I once attended a Christmas party at the house of a single gay man in suburban Seattle. The Christmas tree was huge, and it glistened with lights, but my most striking memory was of his vast living room, his four bedrooms, and his spacious yard. It was clear that except on rare occasions, the house was empty. Nobody slept in three of the four bedrooms. No children played in the yard. The utility of all that square footage lay almost completely in its symbolism. It reminded my host of the convivial home he grew up in. But at the end of the night, his friends drove a dozen-odd miles back to their apartments in Capitol Hill, leaving him alone with his tree.

Of course, today’s scorned neighborhoods and designs could be tomorrow’s status symbols if the culture was to send us a different set of messages about their worth. This is already happening. For years, television largely depicted American family and social life as suburban, but in the past two decades the hip protagonists of programs such as

Friends

and

Sex and the City

were shown in downtown apartments. Formerly low-status neighborhoods such as Manhattan’s East Village have been invaded by the upwardly mobile, and condominium towers designed by starchitects are sprouting between the tenements. New generations are growing up with a different mental library of stories that shape their domestic tastes.