Read Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design Online

Authors: Charles Montgomery

Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design (11 page)

In the beginning, private motorcars were feared and despised by the majority of urbanites. Their arrival was seen as an invasion that posed a threat to justice and order. Drivers who accidentally killed pedestrians were mobbed by angry crowds and convicted not of driving infractions, but of manslaughter. At first, all levels of society banded together to protect the shared street. Police, politicians, newspaper editors, and parents all fought to regulate automobile access, ban curbside parking, and, most of all, limit speeds to ten miles per hour.

But drivers joined with automobile dealers and manufacturers to launch a war of ideas that would redefine the urban street.

*

They wanted the right to go faster. They wanted more space. And they wanted pedestrians, cyclists, and streetcar users to get out of the way. The American Automobile Association called this new movement Motordom.

“They had to change the idea of what a street is for, and that required a mental revolution, which had to take place before any physical changes to the street,” Norton told me. “In the space of a few years, auto interests did put together that cultural revolution. It was comprehensive.”

Motordom faced an uphill battle. It did not take an engineer to see that the most efficient way to move lots of people in and out of dense, crowded downtowns was by streetcar or bus. In the Chicago Loop, streetcars used 2 percent of the road space but still carried three-quarters of road users. The more cars you added, the slower the going would be for everyone. So Motordom’s soldiers waged their psychological war under the cover of two ideals: safety and freedom.

First they had to convince people that the problem with safety lay in controlling pedestrians, not cars. In the 1920s, auto clubs began to compete directly with urban safety councils, campaigning to redirect the blame for accidents from car drivers to pedestrians. Crossing the street freely got a pejorative name—jaywalking—and became a crime.

†

Most people came to accept that the street was not such a free place anymore—which was ironic, because freedom was Motordom’s rallying cry.

“Americans are a race of independent people, even though they submit at times to a good deal of regulation and officialdom. Their ancestors came to this country for the sake of freedom and adventure,” declared Roy Chapin, president of the Hudson Motor Car Company. “The automobile supplies a feeling of escape from this suppression of the individual. That is why the American public has seized upon motor travel so rapidly and with such intensity.”

*

The industry and its auto club supporters pressed their agenda in newspapers and city halls. They hired their own engineers to propose designs for city streets that served the needs of motorists first. They stacked the national transportation-safety conferences staged by U.S. commerce secretary Herbert Hoover in the 1920s, creating model traffic regulations that forced pedestrians and transit users into regimented corners of the street such as crosswalks and streetcar boarding areas. When the regulations were published in 1928, they were adopted by hundreds of cities eager to embrace what seemed like a forward-thinking approach to mobility. They set a cultural standard that has influenced local lawmakers for decades.

Futurama

The first American to earn a doctorate in traffic was a bookish young man named Miller McClintock. After his graduation from Harvard in 1924, McClintock called for strict rules that would restrict cars and cities. Efficiency, fairness, and speed limits were the name of the game. But then the Studebaker car company put him at the helm of a new traffic foundation it funded, and McClintock, who had a new wife and child to take care of, had a philosophical change of heart. With Studebaker’s quiet backing, he became the national authority on streets and traffic while training America’s first generation of traffic experts. His diagnosis for cities came to resemble the aspirations of the auto interests who funded him, and by the time he addressed the Society of Automotive Engineers in 1928, he was sounding a lot like Roy Chapin.

“This country was founded on the principle of freedom,” he announced. “Now the automobile has brought something which is an integral part of the American spirit—freedom of movement.”

In this new age, freedom had a very particular character. It was not the freedom to move as one pleased. It was the freedom for cars, and cars alone, to move very quickly, unhindered by all the other things that used to happen on streets. The enemy of

freedom

, McClintock declared, was

friction

! The nation needed roads unhindered by the friction of intersections, parked cars, and even roadside trees.

At the 1937 National Planning Conference in Detroit, McClintock unveiled spectacular images of that vision: a futuristic city where pearl-hued skyscrapers poked through a latticework of elevated freeways and cloverleafs unsullied by crosswalks or corner shops or streetcars. The pictures, a collaboration between McClintock and stage designer Norman Bel Geddes, had been paid for by Shell Oil. They would grow into the most persuasive piece of propaganda in the history of city planning, when Bel Geddes expanded the model into Futurama, a vast pavilion for the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. Futurama showed people the wondrous world they would inhabit in 1960 if cities embraced the Motordom vision. Visitors were transported in moving chairs over a football field–size diorama where automated superhighways shuttled toy cars between city and country. At the end of the ride, visitors strolled out onto an elevated pedestrian walkway above a perfect street packed with new automobiles. It was a life-size version of the motor age city: the future made real, thanks to the exhibit’s sponsor, General Motors.

Although the model was presented as a free-market dreamworld, it bore a striking resemblance to drawings of Le Corbusier’s egalitarian Radiant City. Two radically different philosophies had fallen in love with technology to produce a similarly separationist vision. But Futurama was distinguished by its reverence for speed. With its sleek highways propelling citizens from orderly cities to pristine open spaces, it seemed to confirm that the fast city really would set people free, as Frank Lloyd Wright had promised.

More than twenty-four million people waited in line to see the future that year. The exhibit, which was featured in magazines and newspapers, drew an entire nation to the high-speed philosophy of its sponsors and helped cement a massive cultural shift toward the automobile lifestyle.

Meanwhile, a company formed by GM, Firestone Tire and Rubber Company, Phillips Petroleum, and Standard Oil was busy buying up and dismantling hundreds of private streetcar lines in dozens of cities across the United States. Various conspiracy theories have argued that this was a plan to force people to buy cars by eliminating public transit. This may have been true, but it was hardly necessary. The streetcar had been fatally wounded when the definition of the street changed. It drowned in a sea of cars.

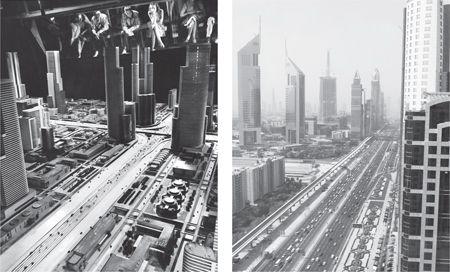

Futurama

LEFT

: The future is revealed at the vast General Motors pavilion for the 1939 World’s Fair in New York: a city built for cars.

RIGHT

: The Futurama vision has now been built into cities around the world. The fourteen high-speed lanes of Dubai’s de facto main street, Sheikh Zayed Road, are impossible for pedestrians to cross for miles at a time.

(

Left

: GM Media Archive;

right

: Charles Montgomery)

The final assault on the old city arrived via the interstate highway system. In 1956 the Federal-Aid Highway Act funneled billions of tax dollars into the construction of new freeways, including dozens of wide new roads that would push right into the heart of cities. This—along with federal home mortgage subsidies and zoning that effectively prohibited any other kind of development but sprawl—rewarded Americans who abandoned downtowns and punished those who stayed behind, with freeways cutting swaths through inner-city neighborhoods from Baltimore to San Francisco. Anyone who could afford to get out, did.

The System That Reproduces Itself

Cities, like many systems, are prone to a phenomenon known as autopoiesis, which can be compared to a viruslike process of entrenchment, replication, and expansion. The dispersed city lives not only in the durability of buildings, parking lots, and highways, but also in the habits of the professionals who make our cities. Once the system of dispersal was established in early suburbs, it began to repeat itself in plan after plan—not because it was the best response to any particular place, but because of the momentum of autopoiesis. It was simply easier for city builders in communities with modest budgets to repeat what worked before, and their habits gradually hardened into the building and zoning codes that dictated how new places would be built. Thus, a segregated land zoning system created to keep industry from creeping into an Ohio village back in 1926 evolved into a national tool and eventually was distilled into standard, downloadable codes sold by the private online purveyor Municode. Cash-strapped towns can now simply download their property-use laws. Meanwhile, road-design laws developed by Motordom-funded engineers were entrenched in the Federal Highway Administration’s

Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices

, or

MUTCD

, a traffic bible guiding most urban road projects in the country. Dispersal infected the operating system of city after city, and those cities in turn replicated dispersal’s DNA.

The rapid, uniform, and seemingly endless replication of this dispersal system was, for many people and for many years, a marvelous thing. It helped fuel an age of unprecedented wealth. It created sustained demand for the cars, appliances, and furniture that fueled the North American manufacturing economy. It provided millions of jobs in construction and massive profits for land developers. It gave more people than ever before the chance to purchase their own homes on their own land, far from the noise and haste and pollution of downtown.

Had he joined the Repo Tour, Andrew Mearns, the clergyman who trudged into London’s slums in 1883, would no doubt note the absence of sewage stench, of desperate crowding, soot, and clambering vermin. He would marvel at the broad lawns, the life-giving sunlight, the peace, plumbing, and privacy afforded each family. And the silence. He would see in the dispersed city a tremendous achievement.

He might not recognize that the pendulum had swung to another extreme. He might have trouble seeing the economic and social devastation caused by the geometries of distance, or the extent to which the system of dispersal had corroded life in other parts of the city. But that system has indeed seeped into every corner of the modern city. It infuses the zoning codes that freeze such first-generation suburban towns as Palo Alto, where Nancy Strausser raised her children, but where none of them or their own children will likely ever be able to afford to live again. It taints central cities, where systems have been reconfigured for speed—not just in neighborhoods lacerated by freeways but also on avenues where traffic signals, asphalt, and sidewalks have been redesigned to favor travelers passing through in private vehicles over the people who live there.

Dispersal has drawn cities into a zero-sum game: as it distilled and privatized some material comforts in detached suburban homes, it off-loaded danger and unpleasantness to the streets of dense cities. It reverberates in the car horns that wake Brooklynites at dawn, and it gets sucked into the lungs of Manhattanites who choose to walk to work.

*

It seeps into once-quiet neighborhoods in suburban Los Angeles, where long-distance commuters barrel through residential streets to avoid now-congested freeways, and children have been banned from playing street ball. It exists in the forgotten schools, neglected public spaces, and anemic transit services endured by residents of some unfavored “inner-city” neighborhoods abandoned by governments and prosperous citizens alike more than half a century ago. Meanwhile, dispersal starves the budgets of cities forced to spend sales tax dollars on roads, pipes, sewage, and services for the distant neighborhoods of sprawl, leaving little for the shared amenities that make central-city living attractive. The fact that residents in America’s central cities report being even less satisfied and even less socially connected than people in suburbia is not a testament to the superiority of sprawl, but a by-product of received hardships and the pervasive, systemic effects of dispersal.

A new wave of urbanists now pit sprawl against the vertical city, arguing that the physical and cultural density of Manhattan is the model for a sustainable future. But the journey to a happier city cannot simply mean choosing between downtown and the sprawl edge. Most central cities, with these layers of imported traffic, noise, pollution, and road danger, do not currently meet our needs for well-being much better than sprawl. We must redesign both landscapes and the fabric that connects them in ways that answer the needs that led us to retreat in the first place.