Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh (21 page)

Read Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh Online

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

Tags: #History, #Africa, #General, #World, #Ancient

The vast majority of the Egyptian people, the peasants and lower classes, would have been ignorant of any struggle for power within the palace. As long as there was a pharaoh on the throne, and as long as the state continued to function correctly (that is, paying out rations), the people remained remarkably content with their lot. However, no pharaoh could hope to rule without the support of the relatively small circle of male élite who headed the army, the civil service and the priesthood. These were the men who effectively controlled the country and kept the king in power. Again, we must assume that these influential men found their new monarch acceptable even if they did not positively welcome a woman at the helm. Why was she so acceptable? Was her assumption of power so gradual that it went unnoticed until it was too late to act, or was there no one else more suitable? Perhaps Gibbon has provided us with the best explanation for this uncharacteristic departure from years of tradition when he observes that:

In every age and every country, the wiser, or at least the stronger, of the two sexes has usurped the powers of the State, and confined the other to the cares and pleasures of domestic life. In hereditary monarchies, however… the gallant spirit of chivalry, and the law of succession, have accustomed us to allow a singular exception; and a woman is often acknowledged the absolute sovereign of a great kingdom, in which she would be deemed incapable of exercising the smallest employment, civil or military.

21

Hatchepsut, the singular exception, had inherited a cabinet of tried and trusted advisers from her brother, many of whom had previously worked under her father and all of whom seem to have been happy to switch their allegiance to the new regime. The two old faithfuls Ahmose-Pennekheb and Ineni were still serving the crown, and Ineni in particular seems to have been especially favoured by the new king:

Her Majesty praised me and loved me. She recognised my worth at court, she presented me with things, she magnified me, she filled my house with silver and gold, with all beautiful stuffs of the royal house… I increased beyond everything.

22

Although Ineni was obviously deeply impressed by Hatchepsut's rule, indeed so impressed that he failed to record the name of the ‘real king’, Tuthmosis III, in his tomb, he never specifically refers to his mistress by her regal name of Maatkare, and it would appear that he died just before she reached the height of her powers. In contrast, Ahmose-Pennekheb omits Hatchepsut from the list of kings whom he has served and offers an unusual combination of her queenly and kingly titles: ‘the God's Wife repeated favours for me, the Great King's Wife Maatkare, Justified’, which would indicate that his autobiography too might have been composed at a time when there was some confusion over Hatchepsut's official title.

Gradually, as her reign progressed, Hatchepsut started to appoint new advisers, many of whom were men of relatively humble birth such as Senenmut, steward of the queen and tutor to Neferure. By selecting officials with a personal loyalty to herself, Hatchepsut was able to ensure that she was surrounded by the most devoted of courtiers; those whose careers were inextricably linked to her own. However, by no means all the new appointees were self-made men and some, like Hapuseneb, High Priest of Amen and builder of the royal tomb, already had close links with the royal family. Hapuseneb may have actually been a distant relation of Hatchepsut; we know that his grandfather Imhotep had been vizier to Tuthmosis I. Other important characters at Hatchepsut's court included Chancellor Neshi, leader of the expedition to Punt, the

Treasurer Tuthmosis, Useramen the Vizier, Amenhotep the Chief Steward and Inebni, who replaced Seni as Viceroy of Kush. After Hatchepsut's death, some of her most effective courtiers continued to work for Tuthmosis III, and there is no sign that they suffered in any way from having been linked with the previous regime.

From the day that Hatchepsut acceded to the throne, she started to use the five ‘Great Names’ which comprised the full titulary of a king of Egypt and which reflected some of the divine attributes of kingship. To the ancient Egyptians each of these names had its own significance. The Horus name represented the king as the earthly embodiment of Horus; the Two Ladies or

nebty

name indicated the special relationship between the king and the goddesses of Upper and Lower Egypt; the golden Horus name had a somewhat obscure origin and meaning; the

prenomen

, which always followed the title ‘he who belongs to the sedge and the bee’ (generally translated as ‘King of Upper and Lower Egypt’), was the first name to be enclosed within a cartouche; the

nomen

, also written within a cartouche and preceded by the epithet ‘Son of Re’, was usually the personal name of the king before he or she acceded to the throne. The

prenomen

was always the more important name, and this was either used by itself, or with the

nomen

. Thus we often find contemporary texts referring to the new king simply as Maatkare (

maat

is the Ka of Re), although her full title was Horus ‘Powerful-of-Kas’, Two Ladies ‘Flourishing-of-Years’, Female Horus of Fine Gold ‘Divine-of-Diadems’, King of Upper and Lower Egypt ‘Maatkare’, Daughter of Re, ‘Khenmet-Amen Hatchepsut’. Similarly Tuthmosis III, often accorded only his

prenomen

of Menkheperre (The Being of Re is Established), was more properly named Horus ‘Strong-bull-arising-in-Thebes’, Two Ladies ‘Enduring-of-kingship-like-Re-in-Heaven’, Golden Horus ‘Powerful-of-strength, holy-of-diadems’, King of Upper and Lower Egypt ‘Menkheperre’, Son of Re ‘Tuthmosis Beautiful-of-Forms’.

Throughout her reign, Hatchepsut sought to honour her earthly father, Tuthmosis I, in every way possible, while virtually ignoring the existence of her dead husband–brother, Tuthmosis II. It is not particularly unusual to find that a young girl brought up in a female-dominated environment feels a strong desire to emulate and impress her absent father, particularly when he is acknowledged to be the most powerful and glamorous man in the land. However, to some observers

this hero-worship went far beyond the natural affection that a young woman might be expected to feel for her dead father:

This [devotion to a dominant father] is a trait which prominent females sometimes show. Anna Freud turned herself into Sigmund's intellectual heir, Benazir Bhutto makes a political platform out of her father's memory, and one is reminded of a recent British prime minister whose entry in

Who's Who

included a father but no mother. Did Tuthmosis I ever call his daughter ‘the best man in the dynasty’, and is this why Hatchepsut shows no identification with other women?

23

Perhaps the most important point here is that all these women lacked an acceptable female role-model and therefore, once they had made the decision to commit themselves to a career in the public eye, had little choice but to follow their fathers rather than their mothers, sisters, cousins or aunts into what had become the family business. Hatchepsut, as king, had no other woman to identify with. She had already spent at least fifteen years emulating her mother as queen and now wanted to advance to king. Of all the women named above, Mrs Bhutto, a lady who is not afraid to use the name and reputation of her father to enhance her own cause, is perhaps the closest parallel to Hatchepsut. More telling might be a comparison with Queen Elizabeth I of England, a woman who inherited her throne against all odds at a time of dynastic difficulty when the royal family was suffering from a shortage of sons, and who deliberately stressed her relationship with her vigorous and effective father in order to lessen the effect of her own femininity and make her own reign more acceptable to her people: ‘And though I be a woman, yet I have as good a courage, answerable to my place, as ever my father had.’

Citing Tuthmosis as the inspiration for Hatchepsut's actions is, however, in many ways putting the chariot before the horse. Tuthmosis I was Hatchepsut's reason to rule, not her motivation, as Egyptian tradition decreed that son should follow father on the throne. Given Hatchepsut's unusual circumstances, she needed to stress her links with her father more than most other kings. Therefore, in order to establish herself as her father's heir – and thereby justify her claim to the throne – Hatchepsut was forced to edit her own past so that her husband-brother, also a child of Tuthmosis I, disappeared from the scene and she

became the sole Horus to her father's Osiris. To this end she redesigned her father's tomb in the Valley of the Kings, emulated his habit of erecting obelisks, built him a new mortuary chapel associated with her own at Deir el-Bahri and allowed him prominence on many of her inscriptions.

Nor was Hatchepsut the only 18th Dynasty monarch to revere the memory of Tuthmosis I; Tuthmosis III also sought to link himself with the grandfather whom he almost certainly never met while virtually ignoring the existence of his own less impressive father. As a sign of respect Tuthmosis III, somewhat confusingly, occasionally refers to himself as the son rather than grandson of Tuthmosis I. Fortunately, the autobiography of Ineni specifically tells us that Tuthmosis II was succeeded by ‘the son he had begotten’, removing any doubt as to the actual paternity of Tuthmosis III. The terms ‘father’ and ‘son’ need not be taken literally in these circumstances; ‘father’ was often used by the ancient Egyptians as a respectful form of address for a variety of older men and could therefore be used in a reference to an adoptive father or stepfather, patron or even ancestor. That Tuthmosis I should be regarded as an heroic figure by his descendants is not too surprising. Not only had he proved himself a highly successful monarch, he was also the founder of the immediate royal family. His predecessor Amenhotep I, although officially classified as belonging to the same dynasty, was in fact no blood relation of either Hatchepsut or Tuthmosis III.

As a king of Egypt, Hatchepsut was entitled to a suitably splendid monarch's tomb. Therefore, soon after her accession, work on the rather understated tomb in the Wadi Sikkat Taka ez-Zeida ceased and the excavation of a far more regal monument commenced in the Valley of the Kings. Following recent 18th Dynasty tradition, this tomb was to have two distinct components: a burial chamber hidden away in the Valley (now known as Tomb KV20) and a highly visible mortuary temple, in this case

Djeser-Djeseru

or ‘Holy of the Holies’, a magnificent temple nestling in a natural bay in the Theban mountain at Deir el-Bahri.

24

Two architects were appointed to oversee the essentially separate building projects, and Hapuseneb was placed in charge of work at KV20 while Senenmut is generally credited with the work at Deir el-Bahri. However, it is possible that the two elements of the tomb were originally intended to be linked via hidden underground passages, and

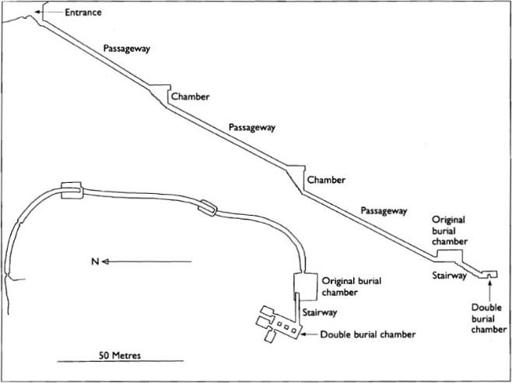

Fig 4.5 Plan of Hatchepsut's king's tomb

an unusually long and deep series of tunnels leading straight from the Valley of the Kings to the burial chamber may have been designed to allow the chamber itself to lie directly beneath the mortuary temple. Deir el-Bahri is separated from the Valley of the Kings by a steep outcrop of the Theban mountain. Today it takes a good half an hour to walk between the two, following the steep mountain trail which had been named ‘Agatha Christie's path’ on the grounds that it plays an important part in her ancient Egyptian detective mystery

Death Comes as the End

.

25

However, the two sites are actually less than a quarter of a mile apart as the mole tunnels. It would therefore have been perfectly feasible for Hatchepsut to be buried below her mortuary temple while enjoying the security of a tomb entrance hidden in the Valley. Unfortunately, the unstable nature of the rock in the Valley of the Kings seems to have thwarted this plan and, in order to avoid a localized patch of dangerously crumbling rock, the straight passages were forced to curve in on themselves, creating a bent bow shape. The finished tomb, if straightened out, would in any case have been approximately one hundred metres too short to reach the temple.

For many years egyptologists have assumed that Tuthmosis I was, by the beginning of Hatchepsut's reign, peacefully resting in Tomb KV 38, which had been built for him in secret ‘no one seeing, no one hearing’ by his loyal architect Ineni. It therefore made sense for his devoted daughter to select a nearby site for her own tomb, KV 20. However, a recent re-examination of the architecture and contents of KV 38 has made it clear that, while this tomb was definitely built for Tuthmosis I, it is unlikely to have been started before the reign of his grandson, Tuthmosis III. This means that, wherever Hatchepsut and Tuthmosis II buried their father, it could not have been in Tomb KV 38. Where then had Tuthmosis I been interred?

It could be that the original tomb of Tuthmosis I has yet to be discovered; his would not be the first tomb to be ‘lost’ in the Valley of the Kings. However, it seems far more likely that Hatchepsut, rather than build herself a completely new tomb, had taken the unusual decision to extend the tomb already occupied by her father by adding a further stairway leading downwards to an extra chamber. This extension would make the tomb eminently suitable for a double father–daughter burial. The proportions of the burial chamber of KV 20, and the unusually small stairway which leads to this chamber, certainly hint

that this section may be a late addition, while its architectural style has indicated a direct link with the Deir el-Bahri mortuary temple which is not suggested by the remainder of the tomb.

26

The inspiration for the double-burial may have been the simple filial love that Hatchepsut felt for her father, or it may have been a more practical move designed to associate Hatchepsut permanently with her ever-popular father's mortuary cult: Winlock has suggested that Hatchepsut needed to use her father's remains to enhance the sanctity of her own burial just as ‘in the Middle Ages the bodies of the saints were translated from the Holy Land to Europe to enhance the sanctity of the new cathedrals'.

27