Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh (36 page)

Read Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh Online

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

Tags: #History, #Africa, #General, #World, #Ancient

Now my heart turns this way and that, as I think what the people will say. Those who shall see my monuments in years to come, and who shall speak of what I have done

.

1

After more than twenty years as ruler of Egypt Hatchepsut, by now an ‘elderly’ woman between thirty-five and fifty-five years of age, prepared to die and live for ever in the Field of Reeds. Her funerary preparations were well underway, her mortuary temple was already established, and Hatchepsut was free to set her worldly affairs in order. Tuthmosis III was her intended successor, and we start to see an obvious shift in the balance of power as the fully mature king emerges from relative obscurity and starts to assume a more prominent role in matters of state. We now find Tuthmosis standing beside rather than behind his stepmother, acting in all ways as a true king of Egypt.

2

Tuthmosis, as commander-in-chief of the army, assumed the onerous responsibility of defending Egypt's borders. Egypt was already being troubled by sporadic outbreaks of unrest amongst her client states to the east; these minor insurrections were to culminate in the open rebellions which dominated much of Tuthmosis' subsequent reign. Tuthmosis now found himself forced to commit his troops to the first of the series of military campaigns which would prove necessary to re-impose firm control on both Nubia and the Levant.

Unfortunately, we have no Ineni to preserve a detailed record of the passing of the female pharaoh but, in the absence of any evidence to the contrary, we must assume that Hatchepsut died a natural death, flying to heaven on the 10th day of the 6th month of Year 22 (early February 1482

BC

). The once popular idea that Tuthmosis, after more than twenty years of joint rule, might finally have snapped and either killed or otherwise ousted his ageing co-ruler seems unnecessarily melodramatic; Tuthmosis must have realized that

he had only to wait and allow nature to take her course. Hatchepsut had already lived far longer than might have been expected, and time was on the young king's side.

To Tuthmosis, as successor, fell the duty of burying the old king in order to reinforce his own claim to rule as the living Horus. We may therefore assume that Hatchepsut was properly mummified and allowed to rest with dignity, lying alongside her father in Tomb KV20. Suggestions that Tuthmosis might have been vindictive enough to deny Hatchepsut her kingly burial have often been made, but again these theories have generally been based on the assumption of Tuthmosis' hatred for his co-ruler which, as we shall see below, has been shown to be an oversimplification of events following Hatchepsut's death.

3

Only one piece of material evidence has been put forward to suggest that Hatchepsut's sarcophagus may never have been occupied. When, in 1904, Howard Carter managed to force his way past the rubble which blocked the entrance to the burial chamber of KV20, he found that the tomb had already been ransacked. The two sarcophagi and the matching canopic chest were lying empty and the remaining grave goods had been reduced to worthless piles of smashed sherds and partially burned fragments of wood. The body of Tuthmosis I had, in fact, been removed prior to the robbery by workmen acting on the orders of Tuthmosis III, and had been trans-ferred to the new tomb, KV38, which was itself in turn to be robbed in antiquity. Inside KV20 the lid of Tuthmosis' sarcophagus was left propped against the wall where the necropolis officials had placed it in order to allow them sufficient room to manoeuvre the body from the tomb. The lid of Hatchepsut's sarcophagus, supposedly dislodged by the tomb robbers, was reportedly found lying intact and face upwards over 5 m (16 ft 5 in) away from its base. This position is

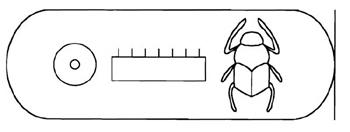

Fig. 8.1 The cartouche of King Tuthmosis III

somewhat unexpected; too heavy to simply lift, we might have expected to find evidence that the thieves used bars and wedges to prise up the lid, allowing it to fall face downwards immediately by the side of the sarcophagus.

4

Could it be that the lid had never been placed on the sarcophagus, and that Carter had in fact found it lying where the original 18th Dynasty craftsmen had abandoned it? By extension, this would indicate that Hatchepsut's body was never interred within KV 20. However, this is a very slight and dubious piece of evidence on which to base a reconstruction of events at Hatchepsut's death. We have no photograph or plan of the tomb at the moment of re-entry, but examination of Carter's painting of the interior of the burial chamber plainly shows both the sarcophagus and its lid, which is not lying neatly on the floor but is roughly displaced on top of what seem to be heaps of debris and smashed grave goods.

5

Carter himself tells us that when he entered the tomb ‘the sarcophagus of the queen was open, with the lid lying at the head on the floor… neither of the sarcophagi appeared to be

in situ

, but showed signs of handling’. It would therefore appear most likely that it was Carter or his workmen who moved the lid to its final resting place while clearing out the chamber.

Fragments of Hatchepsut's anthropoid wooden coffin – a sure indication that she had indeed been accorded a decent burial – were eventually recovered from KV4, the tomb of Ramesses XI, which had yielded broken artifacts from the burials of several earlier pharaohs including, as the excavators noted, ‘numerous pieces of wood from the funeral furniture of some of the kings of the Eighteenth Dynasty… rendered into small slivers that resembled kindling’.

6

It would appear that, during the Third Intermediate Period, the tomb of Ramesses XI had been used as a temporary workshop where the necropolis officials could restore or re-wrap damaged mummies and process the artifacts recovered from earlier burials, in particular those of Hatchepsut and Tuthmosis III. Stripped of their most valuable recyclable aspects (for example, the gilded-gesso surface of the coffin of Tuthmosis III was adzed clean; the gold was presumably melted down and re-used, the coffin was still functional although less decorative and was certainly less likely to attract the attention of tomb robbers) the grave goods were sent together with the bodies of their owners to the cache at Deir el-Bahri for permanent storage.

7

The remainder of Hatchepsut's funerary equipment is now lost, although a draughts-board and a ‘throne’ (actually the base and legs of a couch or bed), said to have been recovered from the Deir el-Bahri cache and presented to the British Museum by the Mancunian egypto-logical benefactor Jesse Howarth in 1887, have been identified as belonging to Hatchepsut on the basis of a wooden cartouche-shaped lid said to have been found with them. However, this identification is by no means certain; the Reverend Greville Chester, who obtained the artifacts on behalf of Mr Howarth, had himself acquired them from an Arab who had supposedly recovered them ‘… hidden away in one of the side chambers of the tomb of Ramesses IX [KV6], under the loose stones which encumber the place’.

8

Hatchepsut's body has never been identified. However, the Deir el-Bahri cache which protected most of the 18th Dynasty royal mummies including Tuthmosis I(?), II and III, also included an anonymous and coffin-less New Kingdom female body together with at least one empty female coffin and a decorated wooden box bearing the name and titles of Hatchepsut and containing a mummified liver or spleen. We are therefore faced with the possibility that these female remains may include either all or part of the missing king. Further anonymous 18th Dynasty female remains have been recovered from the tomb of Amenhotep II (KV 35), which was used as a storage depot for a collection of dispossessed New Kingdom mummies. This tomb yielded sixteen bodies including two unidentified women, either of them potential Hatchepsuts, who are now known as the ‘Elder Lady’ and the ‘Younger Lady’. The Younger Lady is almost certainly too young to be Hatchepsut while the Elder Lady, thought to be a woman in her forties, was for a long time identified as the later 18th Dynasty Queen Tiy. However, recent X-ray analysis suggests that this lady may in fact have been less elderly than had been supposed; she appears to have died when somewhere between twenty-five and thirty-five years of age. It must be stressed that mummy-ages obtained by X-ray analysis do need to be treated with a degree of caution. The suggested X-ray age of thirty-five to forty years for the body of Tuthmosis III is, for example, plainly incompatible with the historical records which indicate that he reigned as king for over fifty years. However, if the analysis of the ‘Elder Lady’ is correct, it would appear that she too may have died too young to be Hatchepsut.

More intriguing is the suggestion that Hatchepsut may be identified with the body of the anonymous lady discovered in KV60, the tomb of the royal nurse Sitre. When it was discovered by Carter in 1903, this tomb still housed its two badly damaged female mummies, that of Sitre herself, and that of a partially unwrapped, obese middle-aged woman with worn teeth and red-gold hair. This lady had been approximately 1.55 m (5 ft 1 in) tall and had been mummified with her left arm across her chest in the typical 18th Dynasty royal burial position. Her obesity had apparently made it impossible for the embalmers to follow the usual custom of removing the entrails via a cut in the side, and she had instead been eviscerated through the pelvic floor. Carter had not been particularly interested in the tomb – he was looking for an intact royal burial which would please his sponsor, Lord Carnarvon – and, leaving things pretty much as he had found them, sealed it up again and departed. The English archaeologist Edward Ayrton had re-entered the tomb in 1906 and removed the lady Sitre and her wooden coffin to Cairo Museum, but the unknown lady had been left lying in a rather undignified position flat on her back in the middle of the burial chamber. The tomb entrance was subsequently resealed, and forgotten. When the American egyptologist Donald P. Ryan re-discovered the tomb in 1989, he provided the lady with a wooden coffin, and subsequently the burial was protected by fitting a door to the tomb. Several authorities have tentatively suggested that this unidentified lady might be none other than Hatchepsut who might have been removed from the nearby KV 20 following a robbery and hidden for safety in KV 60. Less likely is the theory that Tuthmosis III denied his stepmother an official burial and instead interred her alongside her old nurse.

9

The funeral over, Tuthmosis III embarked upon thirty-three years of solo rule. He was immediately faced with revolt amongst a coalition of his Palestinian and Syrian vassals united under the banner of the Prince of Kadesh (a powerful city state on the River Orontes) and backed by the King of Mitanni, and he started a lengthy series of military campaigns designed to strengthen Egypt's position in the Near East. His aim, as he tells us, was to ‘overthrow that vile enemy and to extend the boundaries of Egypt in accordance with the command of his father Amen-Re’. By Year 33 the weaker client states had all been subdued, and Tuthmosis was able to emulate his esteemed grandfather by crossing

the River Euphrates, defeating the army of the King of Mitanni and then returning to Egypt via Syria where, in established Tuthmoside tradition, he enjoyed a magnificent elephant hunt. By Year 42, after twenty-one years of intermittent fighting, the boundaries of the empire were at last secure and Tuthmosis was able to relax into old age. His triumphs, however, were not to be forgotten. Tuthmosis shared Hatchepsut's love of self-promotion, and his campaigns were recorded for posterity and for the glory of Amen on the walls of the newly-built ‘Hall of Annals’ at Karnak, where:

His majesty commanded to record the [victories his father Amen had given him] by an inscription in the temple which his majesty had made for [his father Amen so as to record] each campaign, together with the booty which [his majesty] had brought [from it and the tribute of every foreign land] that his father Re had given him.

10

Towards the end of his reign, his foreign problems now settled, Tuthmosis followed Hatchepsut in instigating an impressive construction programme; there was yet another phase of building at the Karnak temple complex while all the major Egyptian towns from Kom Ombo to Heliopolis plus several sites in the Nile Delta and Nubia benefited from his attentions. In private, Tuthmosis appears to have been a well-educated man of great energy – a real credit to his stepmother's upbringing. Not only was he an action man, a fearless warrior, skilled horseman and superb athlete, he was also a family man blessed with at least two principal wives, several secondary wives and a brood of children. In his spare time he composed literary works and his interests ranged from botany to reading, history, religion and even interior design.

11

Tuthmosis eventually appointed his son as co-regent, and some two years later it was it Amenhotep II, son of Meritre-Hatchepsut, who buried Egypt's greatest warrior king in Tomb KV34 in the Valley of the Kings. Tuthmosis III had reigned for 53 years, 10 months and 26 days.