Hearts West (4 page)

Authors: Chris Enss

The distraught mail-order bride's life was saved by the fast action of her guardian and local doctors. It is not known what became of Eleanor after she was revived and brought back to health. Historians speculate that her broken heart mended and that true love eventually made her forget her first trip to the altar.

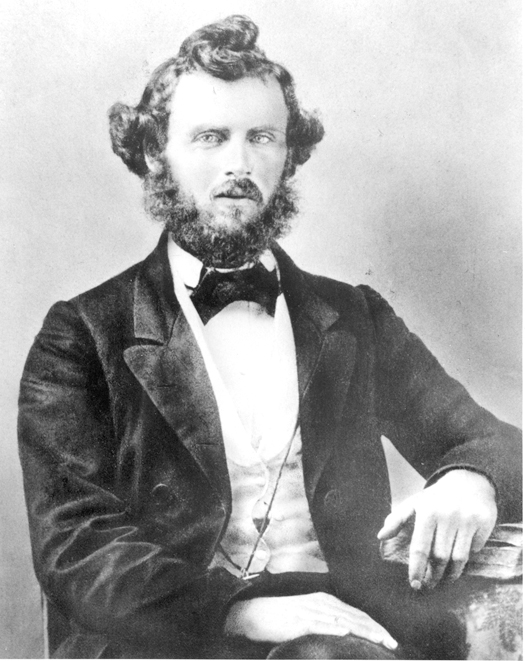

ASA MERCER

Bride Entrepreneur

It is to the efforts of Mr. Mercerâjoined with the wishes of the darlings themselvesâthat the eleven accomplished and beautiful young ladies whose arrival was recently announced, have been added to our population.

Seattle Gazette,

1864

I

n the February 24, 1860, edition of the

Puget Sound Herald,

an advertisement was published that testified to a serious shortage of a desired commodity in Washington Territory:

ATTENTION BACHELORS: Believing that our only chance for the realization of the benefits and early attainment of matrimonial alliances depends on the arrival in our midst of a number of the fair sex from the Atlantic States, and that, to bring about such an arrival a united effort and action are called for on our part, we respectfully request a full attendance of all eligible and sincerely desirous bachelors of this community assemble on Tuesday evening next, February 28th, in Delim and Shorey's building, to devise ways and means to secure this much-needed and desirable emigration to our shores.

Asa Mercer

MUSEUM OF HISTORY & INDUSTRY, SEATTLE

Signed by nine leading citizens, the advertisement was picked up by other newspapers and reprinted across the country. Some of the resulting stories were humorous, but the wide coverage achieved the intent of the authors in broadcasting their need. They had hopes of attracting industrious young women to the rich and rugged Northwest, where a few thousand young men were working on making fortunes in timber, fishing, farming, and other endeavors. The lonely bachelors held several more meetings, but no solid plan to import the desired commodity was formulated, and few suitable women emigrated in response to the advertisement.

The pioneers in Washington Territory had, by 1860, established prosperous communities along Puget Sound and were busy carving out farms and ranches along the coast and toward the foothills of the Cascades. The temperate climate, rich fisheries, and timber resources provided the raw materials upon which to build a comfortable life. The one serious deficiency in this western Eden was that the “fair daughters of Eve” (as one newspaper editor described women) were scarce.

The topic had occupied many column inches in newspapers for several years. “There is probably no community in the Union of a like number of inhabitants in which so large a proportion are bachelors. We have no spinsters,” wrote the editor of the

Puget Sound Herald.

He went on to say that the prosperous and clean-living young men populating the area in 1858 were “eager to put their necks in the matrimonial noose.”

In 1860, Asa Shinn Mercer hit upon a scheme to take the next step in the recruitment effort: He would import the desired commodity by traveling to the East Coast, where women were in abundance, and actively promoting the unequaled advantages of Washington Territory. That idea and its sequel were part of the fascinating career of A. S. Mercer, who found his own bride among those he recruited for Washington Territory.

Fresh from college when he followed his older brother, popular Seattle pioneer Judge Thomas Mercer, to the Northwest, Asa slipped right into place in the ambitious new town. Asa worked enthusiastically to help erect a college, and he became a teacher at the Territorial University when it opened in 1861. He also served as the unofficial acting president when the first man recruited turned down the job, and he helped to recruit new students who could afford to pay the fees, which became part of his compensation.

The lack of marriageable women had become a serious detriment to progress. What good was a university if there were no wives to produce the sons to populate its halls? Seeing an unfilled need, Asa rushed to the rescue. He solicited private contributions to make a trip to the East Coast, and raised enough money to go to New England in 1863, with the hope of bringing back several hundred suitable ladies.

Unfortunately, a special committee had been appointed by the Massachusetts legislature to investigate the excess of females over males in that state, “amounting, according to the census of 1860, to 37,515.” The committee had examined the state's needs for laborers in manufacturing businesses. Fearing that the end of the Civil War would see textile mills reopening, the report discouraged “any project from sending the surplus female population to such Western States as have an excess of males.”

Asa hoped to attract hundreds of people, mostly marriageable women, but he was doomed to disappointment. As a result of his efforts, eleven unattached women paid $225 for passage and boarded the S.S.

Illinois

when it headed out to sea in the spring of 1864 on that “maiden voyage.” The women were welcomed to Seattle, and all but two found husbands. Lizzie Ordway, who never married, was devoted to teaching and eventually became a county school superintendent. Another of the young ladies died, apparently of heart trouble.

Capitalizing on the buzz generated by his success, small though it was, Asa ran for a seat on the territory's governing council. In May 1864, the

Seattle Gazette

enthusiastically endorsed his candidacy.

Mr. Mercer is the Union candidate for joint councilman for King and Kitsap counties, and all such bachelors, old and young, may, on election day, have an opportunity of expressing, through the ballot box, their appreciation of his devotedness to the cause of the Union, matrimonial as well as national.

He won the seat, and served in the Territorial Legislative Assembly through January 1865. Then he undertook another recruiting expedition to the East. “One of the most enthusiastic supporters of my contemplated âraid on the widows and orphans of the East,' as he was wont to call it, was Governor William Pickering,” Asa later recalled.

The day before I started for New York the governor met me, shook my hand warmly, and said: “God bless you, Mercer, and make your undertaking a great success. If you get into financial trouble and need money, do not hesitate to wire me and I will give you help.”

A few months after arriving, Asa sent a letter to the folks back home from Lowell, Massachusetts. It was printed in the

Gazette,

and announced:

The 19th of August I sail from New York with upwards of three hundred war orphansâdaughters of those brave, heroic sons of liberty, whose lives were given as offerings to appease the angry god of battle on many a plain and field in our recent war to perpetuate freedom and her institutions.

Asa asked the citizens of Seattle to prepare to house and care for the young ladies. He vouched for their intelligence and moral character. The papers reprinted his letter and communities immediately appointed welcoming committees, though some were dismayed at the number of women headed for their shores.

While the welcoming committees back home were meeting, Asa was running into rough waters. The

New York Times

endorsed the plan to ship widows and orphans to the new territory, and that sent would-be emigrants to Asa's door. But others sounded dire warnings that Asa was a procurer for the dens of iniquity in the West, and cautioned that those who left the safety of their families and their communities would suffer unmentionable fates.

Newspapers weighed in on the topic all across the country. The “surplus sweetness of Massachusetts spinsterhood” would be wasted in Washington Territory, opined the

LaCrosse Democrat

. The editorial continued:

Dr. Mercer has arrived in Boston and perfected arrangements to return at once with a cargo of Bay State Virgins, in black stockings, candlewick garters, shirt waists, spit curls, green specs, false teeth and a thirst for chewing gum.

Meanwhile, a famous female lecturer, Anna Dickinson, made biting remarks about the scheme, pointing out the odd logic involved in bringing schoolteachers to Washington Territory when it was common knowledge that the northern regions were populated largely by single men. “How your Washington bachelors can be fathers is a subject rather for a hearty guffaw than for any serious debate,” Dickinson pointed out in an article reprinted in the

Alta California

. Her lectures in New England during the fall and winter of 1865 were widely attended and given a good deal of press coverage, which may have reduced the number of people interested in emigrating.

While the newspapers capitalized on the sensational aspects of the plan, Asa's capital was shrinking at an alarming rate. As Seattle historian Clarence Bagley later reported, “He was ever prone to take whatever he urgently hoped for as certain of accomplishment.” Asa's urgently-hoped-for voyage with hundreds of accomplished young women and families, however, was almost stopped on the docks of New York.

The ship that Asa said was to have been made available by the federal government ended up in the hands of another schemer, who demanded a large sum to carry each of the passengers. The money he'd been given by young bachelors to cover costs of bringing back wives was long gone. Funds provided by others to be used for various investments had also been spent.

The delays, the loss of the ship, and finally, the negative publicity caused many of the young ladies and their families to cancel plans to join the expedition.

Five months late and several hundred ladies short, the S.S.

Continental

steamed out of New York Harbor January 16, 1866. Roger Conant, a New York reporter who traveled with the party, reported on the voyage. The departure was marred, says Conant, whose account was supported by several passengers, when some of those who had been promised passage were sent back before the ship left the harbor. Conant's version of events, as related in his journal, tells of an old man with five children being escorted off the ship when he could not pay the passage. The man's money had been used to cover hotel costs during the long delay.

Conant described the departure as though it were a theatrical farce:

The disappointed virgins screamed “Mr. Mercer! Mr. Mercer!!” The gray haired man hoarsely shouted “Mr. Mercer! Mr. Mercer!!” But no Mr. Mercer answered their appeals, and a thorough search of all the state rooms failed to discover his place of concealment.

Finally, the ticket-less would-be emigrants were escorted from the ship and the

Continental

edged out of the harbor.

Where was the hero of the day? Mercer was hiding in the coal bin. Conant describes the removal of the hatch cover once the ship was under way:

A heavy lumbering tread from below heralded the approach of the great benefactor of the virgin race. Soon a shock of red hair besprinkled with coal dust, bearing a strong resemblance to a zebra's skin, appeared below the opening. Then a pair of red eyes lifted themselves to the light. And soon a pair of hands were thrown upward in an appealing manner.

Mercer was lifted from his hiding place by a couple of sailors.

Flora Engle, who was fifteen at the time and traveling with her mother and brother to join her father and sister in Seattle, later wrote a long account of the voyage. Both Conant and Flora said that Mercer paid court to one young lady, but was rebuffed. “Mr. Mercer, who had formed a second attachment and had been so fortunate as to have his passion reciprocated, married Miss Annie Stephens of Baltimore,” Flora reported. Annie's father owned a hat factory in Philadelphia. She and Asa were the same ageâtwenty-sixâand though she was Catholic and he Methodist, they were married in Seattle in July 1866.