Hearts West (10 page)

Authors: Chris Enss

The

Osceolo

traveled a southerly course toward its destination. The further south they went, the calmer the waters became. By the first week of February, nearly all the women had recovered and were enjoying long walks topside. Being able to take in a clear sunset and breathe the fresh air reinvigorated the brides. One evening crewmembers entertained the recuperating ladies with a musical program. A quartet of sailors sang while another member of the crew accompanied them on a mouth harp. Some of the women danced with the men, and afterward they were all treated to a meal of soup and crackers.

On Sunday, February 7, 1865, both passengers and crew congregated on the deck of the ship for Sabbath services. A strong wind again created big swells that pelted the sides of the vessel, but it did not detract from the worship time. One of the older brides-in-waiting gave the sermon and led the group in a hymn and closing prayer. All were hopeful that the hard times they'd encountered while en route to Oregon were over.

As Sunday morning turned to dusk, larger waves crashed against the ship's hull. The water and wind were so loud they overpowered one sailor's call for help. A crewman working near the ship's stern had lost his balance and fallen overboard. By the time his desperate cry was heard it was too late. Life preservers were tossed out, but they failed to reach the man before the strong ocean current swept him away.

Efforts to save the pitiful man did not work. I watched in horror as he drifted further and further out into the gray water and then vanished under a wave. It made us all realize how much we are at the mercy of the sea. May God have mercy on the man's soul.

Constance RanneyâFebruary 8, 1865

A somber mood fell over the hearts of the surviving crewmembers and the women. The tragedy clouded the attitudes of the passengers and February passed slowly for them. By the middle of March, they were restless and anxious to reach the Oregon coast.

How much longer? My seasickness has been replaced by homesickness. I know that it will pass once I am on dry land and have the privilege of meeting the man who will take me as his wife. I can hardly wait another day!

Constance RanneyâMarch 16, 1865

On April 4, 1865, the

Osceolo

pulled into an Oregon port. More than 150 men, loggers, and miners from the Willamette Valley were on hand to greet the women.

The brides disembarked carrying letters of introduction in one hand and the single suitcase they had been permitted to bring in the other. The beautiful landscape was just as the Benton Brothers had described it. Snow-covered mountain peaks, dense forests, and clear water surrounded them and beckoned them on to their new lives.

The brides were happily escorted to the town of Albany. Within a year's time all but seven of the women had married. Constance Ranney's and Jospehine Ann Gibney's journals ended once they reached dry land. The written account of their travels from Maryland to Oregon has been preserved at the Maritime Museum in Portland.

A HAPPY RIDE

A

n excerpt from a newspaper in Northern California describes a controversial event that took place at a gentlemen's club meeting in Nevada County. A group of prominent men, convinced that being single was better than being married, met on a regular basis to discuss the benefits of remaining unattached. The organization's commitment to that belief was challenged when one member dared to follow through with plans to marry his mail-order bride.

One of the many devious ways in which the course of true love can be made to run was illustrated in Grass Valley recentlyâshowing how by a chance buggy ride, a man saved $2000 and gained a wife. A certain young bachelor of Grass Valley paid his “distresses” to one of the beautiful young ladies so numerous in this grassy vale, and matters were rapidly progressing towards a matrimonial entanglement, when for some reason best known to himself the wooing swain “flew the track.” The deserted mail-order maiden was a girl of spirit, and she immediately commenced suit for breach of promise to marry. The trial commenced January 11, 1881, and the contest waxed hot for three days, resulting in a verdict for the fair plaintiff, with $2000 damages.

Consternation was carried into the camp of the bachelors by this threatening result. A meeting of the Bachelor's Club of Grass Valley was instantly called to discuss the situation and deliberate upon precautionary measures, to protect others of the fraternity from the fate that had overtaken their brother. Among other things it was proposed that all members who were in dangerous habit of calling upon marriageable ladies should supply themselves with a receipt book, and have a release signed at the termination of each visit, stating that no matrimonial engagement had been entered into, and that all was square to date.

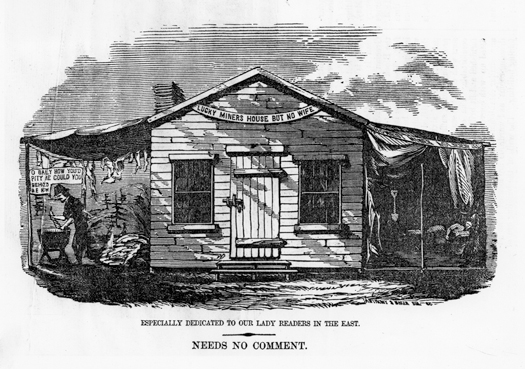

Miners published this cartoon to accompany a poem entitled “We Miss Thee, Ladies”âa proposal of marriage to missing women.

ELEANOR MCCLATCHY COLLECTION, CITY OF SACRAMENTO, HISTORY AND SCIENCE DIVISION, SACRAMENTO ARCHIVES ANDMUSEUM COLLECTION CENTER

In an earnest speech and with a voice trembling with emotion, the president besought the members to specially avoid osculation, as in law a kiss was regarded as a seal to an implied contract making it binding upon the parties. The club adjourned without taking final action, and the members departed to their homes with a deep-rooted apprehension lurking in their bosoms, and resolved to spend their money on billiards and fast horses and let the girls severally alone.

And now comes the romantic termination. About three months later a heavily loaded stage was on its way from Nevada City to Grass Valley, when it was met by a gentleman in a buggy, who offered to relieve the stage of one of the passengers, provided the person was willing to return to Nevada City while he was transacting a little business. The innocent driver gazed down into the stage and asked a lady if she desired to accept the gentleman's offer.

She did desire and did accept, and alighted from the stage which immediately drove away. Then it was that the old-time lovers and recent litigants found that they were destined to take a ride. What was said during that ride we know not, but when they arrived in Nevada City, they went before Judge Reardon, the same who had presided at the trial, and were quickly made one. Indignant at this defection of a member whom they had considered their staunchest adherent, the Bachelor's Club called another meeting and expelled him with imposing ceremonies.”

The

Daily Transcript

âMay 10, 1881

RACHEL BELLA KAHN & ABRAHAM CALOF

Northern Plains Pioneer Couple

T

he clump of yarn Rachel Bella Kahn was attempting to unravel was a mixture of complicated knots and tangles. The seventeen-year-old servant girl painstakingly worked through the mass of thick threads, rolling the straightened strands into a neat, tight ball. Chaya Calof, a graying, older woman from Chvedkifka, Russia, watched the young woman's every move closely. After several moments Rachel patiently and successfully transformed the snarled ball into a manageable skein.

The ball of yarn was politely handed over to Chaya, who grinned from ear to ear. “Good,” she told her, “Good. You've passed the test.” The teenager breathed a sigh of relief. Chaya's approval was all that was standing in the way of Rachel's marriage to the North Dakota farmer seeking her hand.

“A wife of good, strong character is what I seek, but it is optional. To be of the Jewish faith is mandatory,” wrote Abraham Calof in 1892. Rachel Bella Kahn fit all of the requirements set by the twenty-two-year-old man. She was not the first to reply to his advertisement for a bride, nor was she the applicant Abraham had initially selected. Abraham's first mail-order bride choice reconsidered the proposal after her father persuaded her that America was too far away for her to move. Rachel had no such pull in her homeland and believed her sad existence could only improve in the United States. Once she was approved by ChayaâAbraham's sisterâas a suitable candidate for a wife, Rachel eagerly looked forward to beginning a new life in the fertile farmland of North Dakota.

Rachel Bella Kahn was born in 1876. Her mother died shortly after Rachel turned four, leaving her and her three siblings to be raised by their father. A servant girl was hired to help Rachel's father in tending to the children, but the girl was cruel to Rachel and her brothers and sister, denying them food and beating them. Her father remarried when Rachel was eight, but his new wife proved to be as abusive as the live-in help had been. Again the Kahn children were made to go without many of the basic necessities of life and were physically mistreated as well.

Rachel's father turned a deaf ear to his children's complaints of their stepmother's actions. The Kahn youngsters suffered through several years of cruelty. Rachel protected her family as best she could. According to her memoirs, her “childhood passed on slowly in tears.”

At seventeen, Rachel went to work for her aunt as a maid. The job was a difficult one. She spent long hours cleaning the many rooms of her aunt's elaborate mansion, doing laundry, and shopping for the evening meals. Often, the shopping excursion included a trip to the butcher's shop. It was there that Rachel met and fell in love with the butcher's son. Her mother's side of the family, however, would not allow the two to pursue the relationship. They considered his occupation to be inferior and forbade them to see each other.

Rachel celebrated her eighteenth birthday alone and with no prospects for the future. She was convinced she would die an old maid. A solicitation for marriage gave her a renewed hope that she could rise above her desperate situation. Abraham Calof liked what Rachel wrote about herself in a letter of response to his search for a wife. After exchanging photos and finding favor with one another's looks, Abraham commissioned his oldest sister to further interview his prospective bride.

Chaya put Rachel through a series of strenuous tests that challenged her patience and good nature. She won the critical woman over by not becoming frustrated or angry while unraveling the ball of tangled yarn. Chaya agreed that Abraham should marry Rachel and sent her on her way.

Rachel made the journey to America traveling first by train from Brest-Litosk, Russia, to Hamburg, Germany, and then by ship to Ellis Island. She was sick for twenty of the twenty-two days at sea, but quickly forgot the discomfort the minute she saw Abraham for the first time. “There's my beloved,” she told a girl sitting next to her once they arrived in New York. The engaged couple recognized each other from their photographs, and when their eyes met they knew the bond would be forever.

Rachel and Abraham traveled from Ellis Island by train to North Dakota. While en route, the pair got to know one another and Abraham revealed his plans for the future. He wanted to follow in the footsteps of his father and brothers and file a homestead claim on a patch of North Dakota prairie land. Rachel happily imagined the home she and Abraham would have, and the thought alone brought her more pleasure than she had ever known in her life.

Although Rachel instinctively knew the life of a pioneer woman would be difficult, she was not prepared for the display of hardship that greeted her upon her arrival in Devil's Lake, North Dakota. Abraham's parents, brothers, their wives, and children met the couple at the depot. Rachel was shocked by their appearance. They were dirty and dressed in rags. Their faces were weathered and none of the men wore shoes. After the introductions were made, Rachel, Abraham, and the other members of the Calof family climbed aboard an ox-led wagon and took off for their homesteads twenty-five miles from Devil's Lake.

Rachel's spirits were further dampened once they reached the Calofs' combined spread. Abraham stopped the ox team in front of one of three tiny buildings spaced a mile apart from one another. Rachel's heart sank still lower. Their home was nothing more than a rustic 12 by 14 foot, dirt-floor shack. The interior was furnished with a bed, a table made up of wood slats, two benches, and a stove. Until Rachel and Abraham exchanged vows, they would share their place with Abraham's parents, one of his brothers, his brother's wife, and their two children.

Abraham saw the disappointment in Rachel's eyes. He knew the living situation was far from perfect, but believed the sacrifice would be worth it in time. He took his fiancée on long walks, not only to get to know her better but to reassure her that these troubled times were only temporary. Rachel was encouraged by Abraham's promise that in time they would be on their own and happy.

While Abraham worked the fields, Rachel tried to make things as comfortable as she could in the primitive dwelling. Her days were spent gathering fuel for fire and greens for the evening meals, drawing water from a nearby well, and molding lamps out of dried mud. In her leisure time, she and the other members of the Calof family made plans for her and Abraham's wedding.

Rachel's memoirs are filled with tragic tales of frontier living. Her wedding day was one of the happiest times she experienced in those first few years of establishing a life on the rugged plains of North Dakota. The ceremony took place in November of 1894, and was held in the least populated Calof home. The room was decorated with wild flowers and cornhusks. All of the Calofs were in attendance as well as a pair of neighboring Jewish families. Abraham wore an ill-fitting black suit. Rachel was adorned in a wedding dress she had made herself out of yellow, blue, and white striped fabric. The music was provided by the Calof women singing traditional wedding songs, while the men kept time on tin plates.

Jewish custom dictated that Rachel's eyes be hidden throughout the day so that she could shed tears in private. During the ceremony her face was covered with a flour sack and during the reception, her eyes were covered with a cloth blindfold. After the vows were exchanged, Abraham led his bride to a banquet table filled with various dishes of beans, rice, and chicken. Once the meal was over, the couple was presented with wedding giftsâa red felt tablecloth with green flowers, two chickens, and two short women's undershirts.

Their wedding day was a festive occasion, but Rachel's joy turned to bitterness when she realized they would not be spending their wedding night alone. In order to conserve the limited fuel the combined Calof family had, they would be forced to continue sharing their home with several other people and all of the livestock. Frustrated with the living arrangements and irritated with the pungent smell from the chickens and cattle, Rachel's first day of marriage ended with her crying herself to sleep.

Abraham was determined to improve their lot. He worked long, hard hours in the field and tended to the animals. Rachel labored making bread, combing the prairie for mushrooms and other food, and milking the cows. The first winter they shared as man and wife was a cold, harsh one, but an early spring brought warmer temperatures and the glad news that they were expecting a child.

When the time came Abraham and his mother helped Rachel with the birth of the baby. They had a girl and named her Minnie. The infant was wrapped in scraps of Rachel's old shirt. The new parents were woefully lacking in material goods, but compensated for their poor conditions by showering the infant with affection.

Abraham worked nonstop in the fields to turn out a living for his wife and daughter. Rachel strived to keep her baby and herself healthy through a string of tough harvest seasons. At the end of their fifth year of marriage, the Calofs had welcomed another daughter and two sons into the world. Using the income from a successful wheat crop, Abraham built a larger home for his growing family.

By the turn of the century, it seemed as though Abraham and Rachel were on their way to transforming their once-struggling homestead into a prosperous venture. Abraham's wheat crop was the largest yet and harvest time promised to be bountiful. The Calofs would finally be able to do more than simply get by; they would see a profit from their labor.

All hope for a reversal of fortune was dashed, however, when a sudden and fierce storm dumped hail and rain over the ripe fields. It hammered the wheat into the ground and washed away the grain. Many of the Calofs' animals were killed and their home was flooded. After praising God for sparing them, they lamented their loss for a short period and then began at once to rebuild. Many neighboring settlers were unable to rebound from the disaster, but Rachel, Abraham, and their children persevered. Four years and three more children later, the Calofs' farm had fully recovered from the effects of the tragic storm.

By 1910, the Calof homestead had grown to many times the size of the original 160-acre parcel of land they initially maintained. They were not only farming but breaking and buying wild horses as well. They had earned a reputation in the territory for being tenacious and were respected for their dedication to their Jewish faith. Abraham introduced improvements in agricultural practices and marketing to new farmers on the scene, and he and Rachel helped build the first school in the area. The Calofs' efforts were recognized by Presidents William Taft and Woodrow Wilson.

The Calofs had nine children together and were married for more than fifty years. After spending twenty-three of those years on their North Dakota farm, they pulled up stakes and relocated to St. Paul, Minnesota. Abraham settled into the dry goods business and Rachel worked raising funds for a variety of charities. In 1936 she began writing her life's story.

Rachel and Abraham both died from natural causes in their late seventies. Rachel called their marital and pioneer experience “a life worth living.”