Hell-Bent (27 page)

Authors: Benjamin Lorr

In many ways, the biggest lesson to learn from his corrections isn’t in the details. It is his natural, almost unconscious attitude of compassion to those who need it—completely different from his rhetoric while teaching. Watching Bikram make individual adjustments, you realize how much the dogmatic approach that defines Bikram Yoga in many studios is simply a limitation of knowledge. There is only one way, because teachers know only one way.

Bikram Choudhury, on the

other hand, will adjust a single

posture in a thousand ways or, if the case warrants it, throw the whole thing out.

The flipside to this compassion is brutality for those who can handle it. Again, here his instinct is deft. One night, a man is literally “pulled apart” after performing a lackluster backbend. Bikram orders a volunteer to pull his arms backwards while another holds his torso in place. They yank, and the man jerks back in an ugly motion. When he gets up, the man, shy with his long hair, is left shattered, weeping from either the pain or the humiliation.

I spend the rest of the night wondering if I would have had the social strength to object if Bikram had ordered me to be one to pull him apart. Or whether, full well knowing my Milgram, I would have caved and participated.

But by the next day, my anxiety is revealed as amateur. When Bikram orders the man to bend before him again, he eagerly complies with a backbend that is absolutely stunning. A curve deep and smooth and confident.

Bikram crows at the development. “Yesterday he was at zero. Today ten thousand times better. … What is my name? Bikram! Nobody can do that but me.”

If I hadn’t seen it with my own eyes, I would assume it was typical bluster. But there is no denying it. The man was touched. He improved epically at something he cared greatly about. The man knows it too, rising out of his new backbend excited, flushed, and bursting with pride.

The next day, Bikram searches the audience for a woman he remembers from class. She has a rod in her spine, a souvenir from a severe case of childhood scoliosis. Bikram places the woman on her knees, and then slowly coaxes her into a deep backbend—Camel posture. Her rod pokes against her skin. Bikram gently cups the back of her head. Finally the woman emerges upright with a huge flush and tears. In a flash, Bikram yanks her up to her feet like she just won a prizefight.

“That is nothing!” he exclaims. “I used to have a student with

two

rods in her spine. And when she does Camel, it is perfect. Most beautiful thing. I could do Crow [a balancing posture] on her chest holding the boobs.

Nice boobs too. I

have picture!”

Timeless at the 4 A.M. Movie Club

On the last night of TT, after dispatching some irritating business in his suite, Bikram forgoes lecture and instead leads us through a breathing exercise. It is an initiation almost, a meditation that Bikram explains he will teach us exactly as his guru taught him.

“When I was a young man, I used to do this a lot,” he says, sitting cross-legged on his throne. “But I stopped. I want to live among humans, not in some cave in the Himalayas. This breathing is the most incredible thing, but you must be careful. Can easily fall into it, easily spend many hours in meditation, and lose all track of time. … No good if you want to live in the world.”

It is an odd proviso, but with it he begins to instruct us in the technique. Patiently explaining how to wrap our tongues, which phonemes to pronounce on the exhale, and soon we sit and breathe together: completely silently, completely softly, in one rhythm, 381 people. I am very much moved.

After the breathing exercise, Bikram announces there will be a last movie. He tells us it will be optional, but he would like it if we stayed up with him. He says this like a child asking for a gift he knows he just might receive if he is good enough. And I decide, energized by the breathing exercise, joyous that this is our final day of captivity, that just once, I will.

As the rest of the room shuffles off to bed, I push some chairs together into a makeshift bed. Bikram sits with his legs dangling off the stage. Students file past him slowly on the way to the doors. Each and every student who passes says good-bye, some with a head nod, others with a handshake or a hug, sometimes with a suddenly embarrassed rush of tears. There is a realization that after nine weeks, after so much of him, this is the last time we’ll be seeing Bikram for a long while.

When the last student has shuffled past and it is just us who are watching the movie, Bikram unclips his microphone. He loosens his hair from his topknot, and his face relaxes. It is a little after midnight, and the room, spacious in its emptiness, seems to soften in fatigue. Bikram stands up and stretches, then walks up and down the length of the stage by himself,

drowsily, taking it all in. At his throne, he leans over to pick up a pair of slippers. With no assistance, he slides his feet into them and then sits again on the side of the stage: slippers dangling, shoulders slumped slightly forward, eyes closed, the loosest smile over his face.

A senior teacher, one of my favorite staff members, slips behind him and begins massaging his scalp, unasked for and unawares. Bikram’s relaxed smile grows and he does not open his eyes or look up at who is massaging him. He knows. The staff member is smiling too as she rubs, first his scalp and then his shoulders. She has a warm, completely disarmed look to her whole body. Her eyes are half-closed, almost squinting from the pleasure of doing something she knows gives someone else really, really tremendous pleasure. Bikram finally opens his eyes and leans back, looking up at her. They exchange a few words of a conversation I cannot hear. Both laugh. Not the pointed laugh of a joke, but the soft laugh of enjoying each other’s company. Everything in the room has decompressed. There are no students to impress. No stage antics being performed. No big gestures, no microphones, and no sound of his own voice for Bikram to react to. His throne sits empty. The fact that everyone is sleepy makes it feel a little hazy, like a dream sequence in a movie. And for a second, I allow myself to imagine that is what has happened. That we have slipped, not so much into a dream, but into a parallel universe: a Bikram in the here and now, but somewhere far away, a place where he is not a yoga god, nor adored, nor surrounded by adults who have surrendered to his personality—a place where he is not lonely, or angry, or betrayed. Just a man, sitting relaxed, getting a shoulder rub.

Eventually, another teacher walks in, carrying a box full of DVDs. He ask Bikram what he wants to watch tonight. Bikram paws through the box. Paws again. Finally he looks out at the ten or so of us remaining and says, “Well, what do you think?”

Part V

Sickness of the Infinitude

Nauli

A careful scrutiny of various

schools of psychoanalytic psychology reveals general belief in the presence in the human psyche of what I call the “Great Self Within,” a very real inner presence that is not the same as a healthy human self or ego, but can take possession of an ego and drive it to frag—mentation and total destruction. This “Great Self Within,” also called the god—complex or the god—imago, has sometimes been equated with Satan or the devil, but it is very much more complex than the imago of Satan. It is not evil in itself, even though it does fuel the Luciferian tendency.

—ROBERT L. MOORE,

FACING THE DRAGON

A Perfect Upside-Down Linda

Linda is laying out pictures for me on her dining room table. She has this section of her life preserved. In an otherwise aggressively spare house, she has a whole room devoted to her yoga memories. It is choked. There are shelves of photograph albums, drawers crammed with negatives, and shoe boxes upon shoe boxes filled with invitations, hand-drawn diagrams, scrawled notes, and other accumulations of yogic hoarding. At the dining room table, Linda whips through a few carefully selected items: opening lids, tossing chunks of photographs to the side. Finally, she gets to what she is looking for. Pictures from the earliest days.

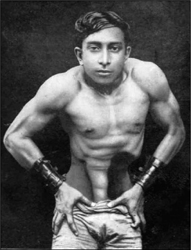

“When I met him, he always dressed the same. White. He liked cleanliness. White pants, white shoes …” She lays out a series of pictures: Bikram at Disneyland pushing his daughter in a stroller, Bikram with his arm slung over another man’s shoulder, Bikram wearing an orange life vest, gingerly stepping onto a boat. And sure enough, there he is in every one: wide smile, straight pants, all in white, looking like an Indian tennis pro.

Linda straightens a photograph. “You can’t see this, but his lips were the

softest lips you have ever touched. Because he took care of them … He was a man who kept himself in the most pristine condition.”

Listening to Linda talk about her time with Bikram in the 1970s, I get goose bumps. To anyone who has read the Bikram dialogue, Linda is someone special. She isn’t just any Linda, she is

the Linda

—“L like Linda”—mentioned in every single class as an example of how to do the postures,

only the third person Bikram

allowed to teach his yoga. She took her first class with Bikram at nineteen and studied with him for the next sixteen years. When Emmy would leave town, Linda taught the Advanced Class in her place. More important than her yoga expertise, however, Linda became someone Bikram clung to, someone whom he needed and loved. They traveled together. They celebrated each other’s weddings. They raised their children together. In her words, she became his shadow.

In his words, he raised her. She says he repeatedly told her he taught her everything he knew.

Linda touches another photo on the table. “This is us on a hike. Maybe 1982. We went in search of a place called Shirley Lake. We called ourselves explorers.” She opens another box, then lays out a series of photographs from the trip. In each, Bikram is grinning, mouth open, like he has just accomplished the most amazing, refreshing thing. “We had so much fun. I don’t think he had ever been to the woods before. … We had to climb up this one hill on all fours. Just laughing and laughing as we climbed.”

She pushes the collection of photographs aside. Paws through another box. “We’d make him presents of us in posture. Photographs. Nothing pleased him like seeing his students. …”

And there they all are, the Bikram regulars of the 1970s: Emmy looking like a young princess in a red one-piece; Tony Sanchez in Om posture, leg slung over his head like a middle school backpack; and in the center, Linda, looking like a young Jodie Foster, in full spine twist.

She opens another box. These are real family as opposed to yoga family pictures. There is a picture of her husband pre–wedding ceremony. There is Linda in a bathing suit, her stomach carved into eight clear abdominal muscles. There are pictures of cake and of Bikram pushing a little girl on a swing. He is in a small backyard at a birthday party for Linda’s daughter.

Behind him there is a cluster of three balloons tied to a post. Bikram looks like the happiest dad on the planet.

“He promoted families back then,” she says. “He was into saving marriages and lives. He counseled people. If he heard about a divorce, he met with the couple and took the husband aside. … He wanted people to value each other.”

She stops to think.

“He would talk and talk and talk and give and give and give.”

She stops again.

“I don’t use the word ‘guru.’ He was my teacher. He took me under his wing.”

For a second, she is lost to the room. In the silence, I stare at a picture of Bikram on the Shirley Lake hike. He is young and eager and powerfully strong. He is striding off to take over the world.

Then Linda comes back.

“It almost didn’t matter,” she says, “the part of him that was not perfect. It almost didn’t matter, because what he did have was a perfect gift. I will always hold on to that. Because I got that from him. I earned it.”

It almost didn’t matter, but it turns out that it did. There is a point where all the boxes of photographs are out on the table, where all the memories are spread out and faceup, and where Linda suddenly stops wanting to talk. We stare at the pictures, thinking very different thoughts. Then she asks me if I would excuse her. She asks if she can get me a piece of fruit from her kitchen. She asks if I would mind if she takes a shower to clear her head.

Then there is a longer silence. Then I push her slightly.

“It got out of control. … And so I removed myself. I released myself. … I was dying. I was dying spiritually, dying physically. … This yoga saved my life. It made my life. But then all of a sudden, I was dying. … I don’t want to say any more. … It got out of control and so I released.”

The Sacrifice to Charis

A 1988 study investigating the personality

traits of eighteen charismatic leaders in New Zealand—a wide collection of gurus, visionaries, eager saviors, and stentorian mongers of the apocalypse—found them, from a phenotypic standpoint, shockingly ordinary. “Indeed,” notes the author and investigator of the study, Len Oakes, “a healthier, more normal-looking profile would be hard to find.” When the numbers were crunched, only three traits stood out as places where the charismatic leaders differed even modestly from the general population: slightly higher creative expression, slightly lower deference to authority, and an elevated sense of personal freedom (called the “free child” subscale in the study).