Hell-Bent (30 page)

Authors: Benjamin Lorr

Or as Chad says, “The biggest lesson that being close to Bikram taught me is dark energy attracts dark energy. At a certain point, Bikram became a magnet. The image of the student flows from the guru. And so if you wanted an excuse to be abusive, you had Bikram acting as an example. If you needed to be a petty tyrant to feel good about yourself, here is Bikram glamorizing being a control freak. … There are plenty of extremely wonderful people in the Bikram world—definitely the majority—but most of them are very frustrated and sad by the fact that there is a whole different set of people running around, acting like mini-Bikrams, screaming and ranting and in general acting like sociopaths.”

Eleanor points me to the psychoanalytic literature. Here the narcissist and codependent are fully intertwined.

Both are children who are not

“seen” for who they actually are: who learn from their parent’s reactions that their natural instincts are unwanted or unwelcome. In both, this becomes a wound or inner vulnerability, where a healthy ego just isn’t good enough. Instead, both as compensation and in an effort to prove worth, these children develop strategies to gain the love denied.

In the narcissist, this becomes the quest for grandiose achievement. In the codependent, this is turned inside out in a grandiose vision of an accepting caregiver or perfect learner. One child chasing admiration, the other desperate for approval. Two sides, same essential coin.

As this need for validation grows into adulthood, the codependent becomes steadily more vulnerable to the narcissist’s greatest seduction: the flattery of mutual admiration, a needed infusion of self-worth. The charismatic narcissist, long practiced at making other people believe he is extraordinary, hooks his audience by making them feel special too—either overtly through compliments or an inspirational message (“you are a gold mine of infinite potential”), divisively by pointing out someone else’s flaws, or more insidiously, simply through the decision to grant his attention. Later, if the narcissist’s power allows, this can extend to creating inner circles where codependents can be rewarded or shunned—where proximity itself is used like a drug—and where ultimately moving closer to the center means allowing deeper hooks like financial dependence, sex, or position in the community to be inserted and used to dominate.

Eleanor ends our conversation by cautioning me. “I know very little about this yoga community, but if you are dealing with a community of individuals who have surrendered to a narcissist, you will find yourself very isolated very fast if you explore this with them. No matter how rational you feel you are being, a person in the thrall of a narcissist has lost all sort of reference point. You can’t talk him out of it, or make him ‘see the light.’ This is a person with a false center, who will tend to react just as hysterically as the narcissist when challenged.”

Yogi-Raj Light of Yogic Learning

One only needs to read the title

of Alice Miller’s

Drama of the Gifted Child

to come to a weak hypothesis. In that work, Miller posits that a child raised by narcissists is denied true love and rewarded only for his or her accomplishments. The child aches for love, and works to get it in the only way the narcissistic parent awards it: by achieving external success. The parent in turn sets up an addictive cycle: Success is rewarded with great beaming displays of joy when the child performs, and love is withdrawn when the child fails. On the outside—clean, quiet, pulling perfect grades—the gifted child gains some relief from all the praise they earn, but the inner self—denied

any affection, desperate for love for love’s sake only—grows increasingly needy, insecure, and tormented.

In that book, Miller writes:

It is one of the turning points in analysis when the narcissistically disturbed patient comes to the emotional insight that all the love he has captured with so much effort and self-denial was not meant for him as he really was. In analysis, the small and lonely child that is hidden behind his achievements wakes up and asks: “What would have happened if I had appeared before you, bad, ugly, angry, jealous, lazy, dirty, smelly? Where would your love have been then? And I was all these things as well. Does this mean that it was not really me whom you loved, but only what I pretended to be?”

Accordingly to Eleanor Payson, the golden age for narcissistic development is three to five years old. It is when a child is most vulnerable emotionally and biochemically.

Three years old is, of course, precisely when Bikram was first introduced to yoga. It was when his inner worth became synonymous with his postural depth and self-denial. When he lost his mother for an indefinite apprenticeship that involved fourteen hours a day at the hands of a mad, charismatic sometimes sadist who punished his imperfections with burns and who extremely rarely—when Bikram was at his absolutely cleanest, best, least lazy, and most dedicated—rewarded him with slight praise. A man whom his absentee parents revered, who with his overmuscled physique and legion of overmuscled followers was almost a superhero figure of powerful male dominance. This was Bikram’s formative experience. This was how he learned to value himself.

And so now when I hear him say to his wealthy clients: “I’m not going to be your American momma.”

Or: “I

hate

lazy people.”

Or when he sneers: “No, sweetie, don’t push yourself. …”

Or: “You know biggest problem in your life? You never work. You always have big American momma saying, ‘Take it eaasssy, baby.’”

It’s hard for me to hear anything except a form of wishing, almost

prayer: his lectures endless and repetitive tirades against comfort and love because if repeated enough, perhaps those sentiments could become true. Like all good critiques, Bikram Yoga began primarily as a self-critique: If only I could rise to this ideal. If only that ugly whining internal voice fell in line with the sentiments my external self is vocalizing.

Bikram found a home in America. Beverly Hills loves an orphan. All those movie stars intuitively recognized one of their own. They grabbed on to his critique because it was the one they had been giving themselves. Who is more insecure about the love, praise, and adoration they receive than the Hollywood starlet? Who has a valuation as transparently false as the silicone gel in her cheekbones? And then all the AAs, NAs, the abused, the damaged, the chronically ill, the borderlines, all of us seekers, all with our holes to fill, we came next. We couldn’t help ourselves. I’m not talking about most people who step inside a Bikram Yoga studio. I’m not talking about the ones who can walk away. Just us, the hell-bent.

An hour and a half of staring at ourselves in the mirror, of self-critique being masked as self-improvement, of being told we were healing because we were punishing ourselves. It was and is irresistible.

Listen again to Mary Jarvis describe the present moment, her goal for practicing the yoga: “In the present moment, you can’t feel pain, you can’t be snotty, you can’t be sad.”

Which is of course why Bikram—by being hopelessly damaged—is exactly the doctor we needed to get the message. He is the guru the living curriculum conjured up for our damaged egos. He is perfect and sad, and we needed him to explain to us how to be perfect within our sadness too. This is precisely where for me it gets complicated and self-referential. Where the tragic flaw is also the key quality that enables the success. A “better” guru would never have been our mirror. A “better” guru would never have given us this yoga tool.

36

And so I can’t help but think that this is the last truest requirement of Bikram. A special opportunity. In part because of Bikram’s dedication to truth as he see it, in part because of his recklessness, we have a legitimate chance to kill our guru. Kill him just as he explains we need to kill ourselves during every class. And once we have done that—really done that, in an open, thorough, and probably horribly difficult process—once we have sacrificed our notion of him completely, maybe we can love him again. I know the community will be stronger. I also know, just as with a single class, a half-assed approach isn’t going to work. We can’t skip directly to the “love him” phase without doing the hard work first. Ignoring things, looking the other way at disturbing, dangerous tendencies—those attributes we are complicit in, which are in fact fueled by our adulation. We can’t continue explaining to other people as well as ourselves, that, well, I can see him as a flawed man and I can take the good with the bad or I just gotta love him, I mean, he’s Bikram, one of a kind, without ever honestly dwelling on the really bad parts, or the fact that uniqueness and charm are no inoculation against sexual manipulation and sociopathic greed. To do anything less is the community equivalent of walking out of a class because it’s just too damn hot. And for those who must see every quality of Bikram in a positive light, perhaps see this as his greatest gift of all. See him as a perfect guru because he is so thoroughly imperfect and thus

all the easier to discard

.

Part VI

All Lies Are Aspirational

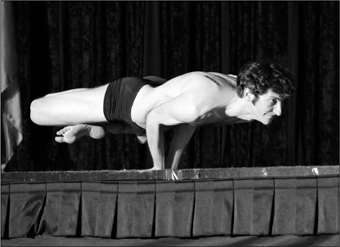

The author, competing in the 2011 Yoga Asana Championships

The true opponent, the enfolding

boundary, is the player himself. … The competing boy on the net’s other side: he is not the foe: he is more the partner in the dance. … [In tennis], you compete with your own limits to transcend the self in imagination and execution. Disappear inside the game: break through limits: transcend: improve: win. Which is why tennis is an essentially tragic enterprise. … You seek to vanquish and transcend the limited self whose limits make the game possible in the first place. It is tragic and sad and chaotic and lovely. …

—DAVID FOSTER WALLACE,

INFINITE JEST

The Song of Solomon

Before our first class, we meet in the locker room. Without his shirt, Sol has the sad body of a circus bear. An exhaustion of grayish flesh, lumbering and emotive in itself. Pocked and microcreased, whole sections giving way like an overstretched plastic bag. It is amazing how much depredation clean baggy clothes can hide. I see the incision from his gall bladder surgery where the little bag that collecting his drippings interfaced with his body.

We set up on opposite sides of the room. We clasp our hands under our chin for the opening breathing exercise, and class begins.

As in all classes, I quickly lose track of myself within myself.

At a transition between postures, I sneak my only glance at Sol. He is lying flat on his back, chest heaving up and down, eyes locked on the ceiling, terrified—this massive respirating clump of flesh: just a few gulls away from a beached marine creature. I think of Ashley. At least from that position, he isn’t going to hurt himself. Then I resolve not to look over again.

I never ask him about class. Instead, we conclude in the locker with a

ritualistic swilling of vitamins and electrolyte powder I have decided we need to take every day. Sol very formally shakes my hand and then staggers out; instead of heading off to his office, he decides to go back home “for a while,” which I think sounds safe enough for Ashley’s purposes. Later, we talk on the phone, and he describes himself as sore but excited.

Day two was a success in that Sol showed up; it was worrisome in that he fled the room at Camel posture. He explained later he thought he heard his cell phone alarm ringing in the locker room and decided he should leave to turn it off. I nodded and just hoped he would return for day three. He did. Day four, Sol announced he was having trouble walking. His legs felt like they were on fire. Day five he said he hurt all over and was cramping up while sitting at his desk. But he kept coming.

As per our agreement, Sol took the first Sunday off to rest. That night, the city was hit with one of the worst snowstorms of the year. School was closed. The subways struggled. I called Sol to discuss skipping class. But he dismissed the offer without consideration. “As long as the teacher’s there, I don’t have much excuse.”

The teacher made it. And then we were off. By day fifteen, when I expected Sol to be struggling the most, he declared he loved the yoga. He actually used the word

love

.

37

He told me he was getting the best sleep of his life.

The Super Bowl coincided with a rest day, and Sol got atrociously drunk—but he showed up for the evening class of day twenty-one anyway. By day thirty he declared he was done with rest days. The studio offered a free month of unlimited yoga to anyone who did thirty days in a row, and Sol announced that he was going to earn it.

Friends kept coming to bend with us. Two came from out of state, each staying for a week. Another dropped in for a single class and ended up buying the monthly pass. But instead of acting as pit crew, pushing Sol forward, they were an audience to his performance.