Henry V as Warlord (25 page)

Read Henry V as Warlord Online

Authors: Desmond Seward

Henry V’s father-in-law, King Charles VI of France, with his counsellors. (The Mansell Collection)

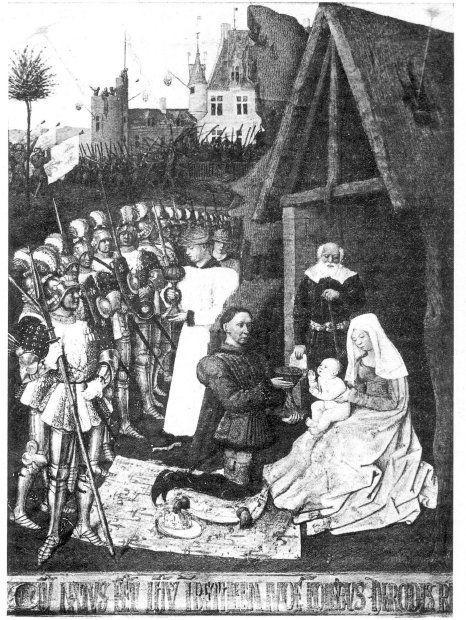

Henry V’s brother-in-law the Dauphin, with King Charles VII, as one of the Three Magi. From a miniature by Jean Fouquet. (Giraudon)

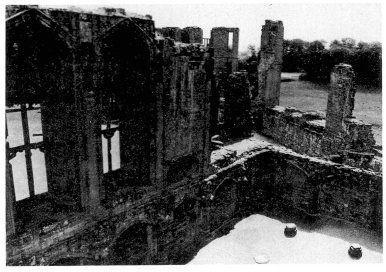

A room well known to Henry V – the ruins of the dining hall of Kenilworth Castle in Warwickshire. (John Cooke Photography)

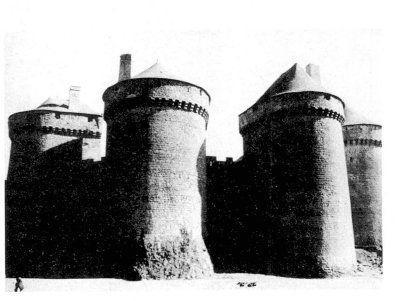

The château of Lassaye in Maine. Destroyed in 1417 to stop it being used as a base by the English, it was rebuilt in 1458 with cambered walls designed to resist siege artillery of the type used by Henry V. (S. Mountgarret)

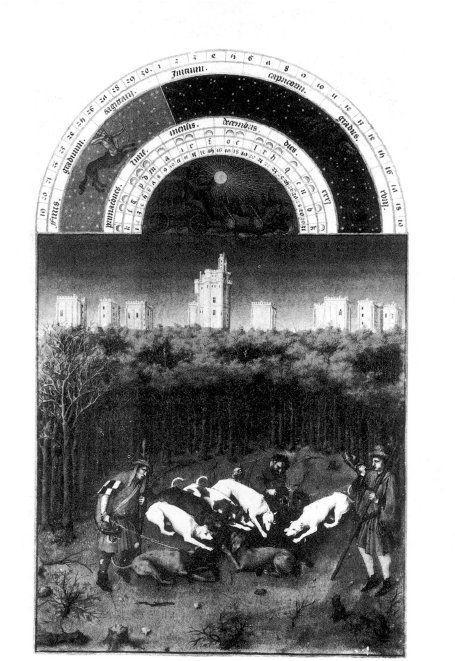

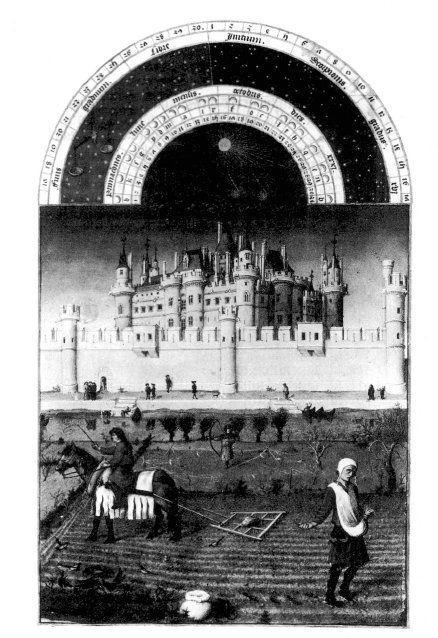

A hunting scene of a sort very well known to Henry V. In the background is his favourite French residence, the castle of Bois-de-Vincennes. From the

Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry

. (Giraudon)

Henry V’s official residence in Paris, the Louvre, as it was in his time. From the

Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry

. (Giraudon)

English links with Scandinavia were closer than at any time since the eleventh century. Henry’s sister Philippa was the queen of Eric XIII, King of Sweden, Denmark and Norway. Her husband’s great-aunt, St Bridget, had presided over the creation of the triple monarchy, now in a state of chronic unrest. The links had been responsible for the foundation of the Bridgettine monastery at Twickenham, its first nuns and monks being Swedes from Vadstena. Probably they were also why Henry employed the Dane, Sir Hartung von Clux (whom he made a Knight of the Garter) in so many capacities. Hartung led embassies to the Emperor Sigismund and also fought in France. In 1417 he brought four men-at-arms, nine archers and, most unusually, two crossbowmen to the invasion force. Later that year he was appointed captain of Creully and he was among the first to be given a Norman estate.

Henry’s diplomacy reached as far as the land of the Teutonic Order on the Baltic. That extraordinary country, stretching from the Neumark of Brandenburg to the Gulf of Finland, was ruled by celibate German knights who waged war on Europe’s last pagans, the snake-worshipping Lithuanians, and less admirably on the Catholic Poles. In 1410 the latter had inflicted a crushing defeat on them, killing their ‘

hochmeister

’. However, the Order remained rich and powerful, with its capital at the Marienburg and commercial centre at Danzig, it was of vital importance in Baltic trade and still wielded considerable international influence; in 1407 the Duke of Burgundy had tried to involve the

hochmeister

in a war with England. Every year a fleet sailed from Danzig to England, joining the fleet of the Hanse towns en route, laden with Prussian goods – corn, silver, furs, falcons and amber. It took home English cloth which was sold all over Poland and western Russia. It was important for the English to keep on good terms with the knights. In 1419 Friar Netter led an embassy to them, and also to King Ladislas of Poland with whom the Order was still at war.

The man whom Henry used most for diplomatic missions was Sir John Tiptoft, the former speaker and treasurer. He played an invaluable part in the negotiations to isolate France before the campaign of 1417, visiting the emperor and many German princes, the Kings of Aragon and Castile, and the republic of Genoa. He was among the commissioners who tried to manoeuvre the French into accepting Henry’s terms in 1419. During all this time he was also Seneschal of Guyenne, having been appointed in 1415, shortly before Henry sailed on his Harfleur expedition, to the most important office in the duchy.

The king never had time to visit Guyenne, although he demanded more and more money from it. He paid the duchy careful attention nonetheless, as is shown by his appointment of Tiptoft, and by that of Sir John Radcliffe as Seneschal of Bordeaux. He was tactful when dealing with the citizens of Bordeaux, writing frequently to the mayor and burgesses to tell them of his progress and asking them to send him news of themselves. The Gascons were firmly tied to England, partly because it bought so much of their wine, and they rejoiced at their king-duke’s victories in the north. He employed Gascon troops, one of his most redoubtable captains being the Captal de Buch, whom he made a Knight of the Garter. Yet Guyenne had its problems, suffering from dauphinist raids and brigandage. It was essential to make sure of two great southern magnates whose territories bordered the duchy, the Counts of Foix and Albret. This involved Henry in much tortuous diplomacy and a considerable outlay in cash.

Tito Livio tells us that the most devout king of England returned to Rouen to keep the feast of Christmas, 1419. However, although Henry himself may have been given up to devotion during this sacred season of the year, at the same time he sent his captains out to conquer further tracts of France. The English troops, who ‘feared not the death for the recovery of the king’s right … remained conquerors in the field and put their adversaries to flight, of whom they first slew many and many they maimed’. Meanwhile, Henry ‘persevered in the city of Rouen lauding and honouring the sole creator and redeemer of the world’.

10

‘

No king of England, if not king of France

’

Shakespeare,

King Henry V

‘Shall I tell of the ruin of Chartres, of Le Mans, of Pontoise – once a most distinguished and flourishing place – of Sens, of Evreux, and of so many other places which, taken by trickery, perfidy or treachery, not just once but again and again, were completely delivered up to pillage?’

Thomas Basin,

Vie de Charles VII et Louis XI

I

n February 1420 Duke Philip of Burgundy made public knowledge the treaty which he had agreed with the King of England at Christmas. Joint Anglo-Burgundian military operations had already begun. While the Burgundians had no objection as Burgundians to capturing and besieging Armagnac strongholds in northern France, as Frenchmen they disliked intensely the English practice of massacring or taking prisoner Armagnacs who had surrendered only after Burgundians had offered them life and a safe-conduct. Yet somehow the uneasy alliance survived, and even prospered. The two armies captured many towns and cities – among them Rheims, where the kings of France were traditionally crowned.

It was essential for Henry and Philip to obtain the support and co-operation of Charles’s queen, Isabeau of Bavaria, who claimed to be Regent of France. Fat and fortyish – she had been born in 1379 – at her court in Troyes she surrounded herself, as she had always done, with gigolos and a menagerie including leopards, cats, dogs, monkeys, swans, owls and turtle doves. Despite having given her husband twelve children she was notoriously promiscuous. Preachers rebuked her publicly to her face for making her court an ‘abode of Venus’. After Agincourt the English king had told Charles of Orleans that he need not be surprised at being defeated, on account of the sensuality and vices prevalent in France – he was referring to the court of Queen Isabeau. One of her affairs had left her with a bitter and ineradicable hatred of the Armagnacs. In 1417 King Charles had briefly recovered his wits, whereupon the late Count Bernard of Armagnac had informed him that his consort was sleeping with the young Sieur Louis de Boisbourdon; the king immediately had Boisbourdon arrested, horribly tortured, tied in a sack and thrown into the Seine to drown, while imprisoning his erring wife at Tours under a penitential regime. Previously she had been inclined to prefer Armagnacs to Burgundians but this episode made her change her mind. In response to her anguished pleas, Duke John sent 800 men-at-arms to rescue the Queen from a miserable captivity and helped her establish her court at Troyes. The incident had also set her against the Dauphin Charles, who had taken the opportunity to plunder his mother’s treasury. Isabeau was unreliable, vicious-tempered from gout and a prey to agrophobia. Yet, while largely disinterested in politics, she possessed a powerful sense of self-preservation.

The alarming English warrior king was an ally who could ensure her survival and her luxuries. Understandably, any comparison with the Dauphin Charles made the latter seem a doomed weakling in her eyes. When the dauphin’s chosen friends killed Duke John on the bridge of Montereau, they had branded him indelibly as a murderer, however much he might protest his innocence. Besides appropriating his mother’s money and jewellery, he had excluded her from any share of power. Even so, she had tried to reach some sort of understanding with him, but the Burgundians skilfully blocked her attempts. They also ensured indirectly that she was kept short of money – the dauphin being as yet too naïve to offer her financial assistance – and promised her through Duke Philip’s mother (her Bavarian aunt) that if she did as they wished they would see she continued to live as she pleased. In addition King Henry sent a personal envoy, Sir Lewis Robsart, a naturalized Englishman whose first language was French, to convince his prospective mother-in-law that he would give her anything she wanted. As early as January 1420 Isabeau issued an edict publicly condemning her son Charles and his actions, recognizing Henry and Duke Philip as her husband’s official allies. Soon it was widely if erroneously believed that she had confessed that Charles VI was not the father of the Dauphin Charles; while undoubtedly she had taken many lovers and it is not entirely impossible that he really was a bastard, it is extremely unlikely that she would ever have admitted it. (During the mid-1420s her son is known to have been extremely worried about his parentage.) The bastardy story was certainly circulated for all that it was worth by Henry’s agents.