Here Comes the Night (35 page)

In the twenties, boisterous singer Texas Guinan used to shout “Hello suckers” from atop a piano on the premises, but the West Fifty-Fourth Street institution had been the unofficial clubhouse of the record business for some time. Leiber pulled up a chair and joined the two pirates. Of all things, Jerry Leiber had never met George Goldner before.

“Can you believe this schmuck,” said Weiss, puffing a cigar. Goldner had been going through tough times and he apparently had come to Weiss to see about working for Weiss’s Old Town label, a marginal operation at best. Weiss, like a lot of his bunch, mistook being a pain in the ass for being funny. He took pleasure in rubbing Goldner’s face in it for Leiber’s benefit.

Goldner

was

one sorry son of a bitch. After losing his End and Gone labels two years earlier to, guess who, Morris Levy, Goldner spent the next year and change doing Levy’s dirty work on record promotion, a field Goldner practically invented and at which his skills were unsurpassed. He left Levy nine months before and had not been able to get a single thing going in the meantime. He was broke, down on his luck.

He had submitted a remarkable letter in 1964 to the register of copyrights at the Library of Congress: “This is to acknowledge,”

Goldner wrote, “that the attached schedule of compositions which contain my name as writer should properly have the name Morris Levy in my place.” The schedule listed forty-nine such compositions, including “Why Do Fools Fall in Love.” He lost his publishing, his labels, and with this single document, his copyrights. By some inexplicable accident, all the songs previously credited to Goldner actually should have been credited to Morris Levy. Once again, Levy took everything.

His French cuffs, perfectly presented, Leiber noticed, were frayed. Weiss offered Goldner some chump change. Goldner tried to negotiate, but Weiss excused himself to go to the bathroom. Leiber turned to Goldner and asked if he would be interested in doing something with Leiber and Stoller. Goldner asked for the keys to Leiber’s office and left Al and Dick’s to listen to acetates.

The next morning, Leiber went to work and found George Goldner, not a hair on his head out of place, standing behind Leiber’s desk, holding a disc. “On my life,” he told Leiber, “this is a hit record.”

Leiber hated the track, but his partner Mike Stoller always thought there was something there. Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich produced the number with a girl group called the MelTones brought to them by New Orleans bandleader and entrepreneur Joe Jones (“You Talk Too Much”). Barry and Greenwich wrote the song with Phil Spector, who first cut it with the Ronettes, and then with the Crystals, but refused to release either. After back and forth with Spector on the publishing, Barry and Greenwich and Mike Stoller took Jones’s vocal trio—who thought they were going to be called Little Miss and the Muffets—into the studio and recorded the song “Chapel of Love.”

It was one of a stack of unreleased masters left over from the UA deal that had built up since they closed down their Tiger and Daisy labels the previous November. Leiber and Stoller formed a partnership with Goldner, whom Stoller had never met before either, and started Red Bird Records. As Goldner predicted, “Chapel of Love”—by the

time it was released, the group was renamed the Dixie Cups—shot to number one in a dizzying six weeks after it was released in April 1964.

They didn’t know it at the time, but Red Bird Records was the beginning of the end for Leiber and Stoller. They were kids from Los Angeles who hit the big time in the record business before they knew what had happened to them. With their own musical career in decline, they had compensated with savvy, knowing work as music publishers, slowly expanding into the record business, a realm, as it turned out, they knew nothing about. With the label’s first release number one and more hits in the pipeline, at first, they had to deal with success, which is infinitely more difficult to handle than failure.

RED BIRD LAUNCHED

sixteen charts hits in twelve months during the absolute peak of what came to be called the British Invasion. Received wisdom holds that the onslaught of fresh, exciting young British beat groups wiped out the cobwebbed old music business in New York, which was hardly the case. Not only was much of the early days of the British beat movement based in the New York rhythm and blues scene, but many of the Broadway rhythm and blues moguls continued, regardless, to thrive and prosper. Berns was not the only one having the best year of his life on the charts.

Burt Bacharach and Hal David were also cutting through the flood of British pop clogging the charts the first quarter of the year. The team continued to have success with Gene Pitney after “Only Love Can Break a Heart” with songs such as “True Love Never Runs Smooth” and “Twenty Four Hours from Tulsa.” They started a series of remarkable, underrated productions with vocalist Lou Johnson for Johnny Bienstock at Big Top with “Reach Out for Me.”

Beginning with their Top Ten in 1963 for Bobby Vinton, “Blue on Blue,” Bacharach and David became an exclusive songwriting-production partnership. They scored a massive, unlikely hit with a jazz waltz composed on assignment for the title song to the movie

Wives and Lovers

, sung and swung by Jack Jones. But it was the back-to-back Top Ten hits—“Anyone Who Had a Heart” and, especially, “Walk On By”—that established not only Dionne Warwick as the new female pop vocal star of the year, but also Bacharach and David as the hot new young songwriting team after more than eight years of having their songs recorded.

That Dusty Springfield took an Anglicized version of their “Wishin’ and Hopin’” into the Top Ten that summer only galvanized their growing standing. The Dionne Warwick hits reversed the thinning fortunes of Scepter Records, where Florence Greenberg was having difficulty adjusting to life after Luther Dixon.

Bob Crewe was also reaching new heights of success in the midst of the British onslaught with the Four Seasons, who were scoring the biggest hits of the vocal group’s estimable career. Baroque pop productions like “Dawn,” “Ronnie,” and “Rag Doll” gave the group their best chart numbers since they blasted into business with three straight number ones two years before in 1962 (“Sherry,” “Big Girls Don’t Cry,” and “Walk Like a Man”).

Producer Crewe was an extravagantly extroverted personality, a onetime fashion model and pop singer himself, who lived in a sprawling penthouse in the nineteenth-century apartment building on the edge of Central Park called the Dakota. The offices of his company, Genius Music, were in the same office building as Atlantic Records, where a receptionist sat directly opposite the elevator doors in front of a sign that spelled out in six-foot letters GENIUS.

It was also a breakthrough year for Motown Records, the bootstrap independent from Detroit started by former car plant worker and the Jackie Wilson songwriter Berry Gordy Jr., who also wrote Marv Johnson’s hits. His team of ambitious black professionals modeled their production methods on the automobile plant assembly line where Gordy worked and aimed their rhythm and blues records at white teenagers. Gordy liked to gear songs toward everyday experiences,

looking for those low common denominators in his audience, and always, always had a tambourine on his tracks because he thought the radio was the call to church. He discouraged bravura performances and sought a sturdy tunefulness that acted as a reassuring agent against any melancholy or distress that might be part of the song’s emotional landscape.

He often conducted the experiments in the studio himself, but also trained a platoon of songwriter-producers schooled in his philosophies. The unblinkingly candid “Money (That’s What I Want)” by Barrett Strong in 1960 started it off for Gordy and company and they refined their attack until they began consistently hitting their target with uncanny accuracy. “My Guy,” a Mary Wells performance written and produced by top Gordy acolyte Smokey Robinson, made number one in May 1964, followed before the end of the year by the first two of five consecutive number ones by Gordy’s most superb creation, the Supremes, a group whose smooth assimilation of pop platitudes was as remote from the kind of raw desperation of Berns’s records as you could get in rhythm and blues.

Phil Spector was also at the peak of his magnificence. Spector hated to fly, but he was convinced the Beatles were going to make it in America. So when he flew home from London in February 1964, he changed flights so he could fly on the same plane as the lads from Liverpool. He walked down the gangway in a floppy cap behind the boys, as thousands of cheering teens greeted their arrival in New York.

In London, Spector had spent a drunken evening in the studio with another new British rock band, the Rolling Stones, lending his hand to the production of what would become the group’s breakthrough U.S. single, “Not Fade Away.” He was involved in a torrid extramarital affair with lead vocalist Veronica Bennett of his new girl group stars, the Ronettes, whose smash debut single for his Philles label written by Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich with Spector, “Be My Baby,” Spector’s most Wagnerian production yet, went to number two in October 1963.

On his latest creation with the group, Spector marshaled nothing less than the heavens themselves, as he wove thunderclaps and rainstorms into the orchestrations on “Walking in the Rain,” cowritten with Mann and Weil, an ethereal, billowy, self-conscious masterpiece that nevertheless only reached the midtwenties on the charts. Spector countered with his towering “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling,” a song he handcrafted for blue-eyed soul duo the Righteous Brothers once again with Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil.

On the grand, confident production, Spector plays a cat and mouse game with the two lead vocalists, only bringing them together finally over the bridge before the explosive final chorus, the conga drum leading the breakdown into a Latinized section that could best be described as a tribute to Bert Berns. The part could have been lifted straight from one of his records.

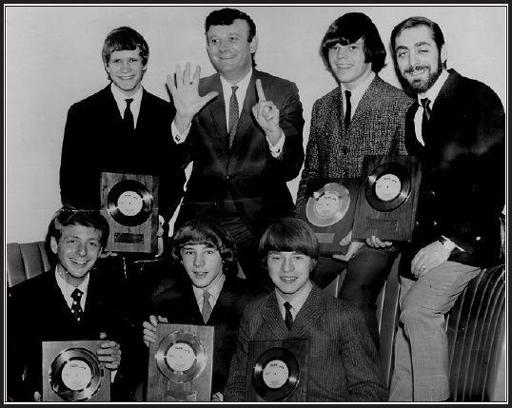

Outside Spector’s domain, Barry and Greenwich were also flourishing at the new Red Bird Records, housed in the Trio Music suite in the Brill Building. They quickly followed “Chapel of Love” with “I Wanna Love Him So Bad,” a Top Ten hit for the Jelly Beans, four gals and a guy, still in high school, from Jersey City. Right from the label’s first release, Goldner was picking hits, promoting Red Bird records on the radio, and making his distributors work them. “George Goldner has the musical taste of a fourteen-year-old girl,” said Jerry Leiber, with more than a trace of admiration.

With Leiber and Stoller acting as executive producers, Barry and Greenwich wrote the songs and produced the records. They conducted the sessions at Mira Sound with engineer Brooks Arthur, whom they knew from his days at Associated Sound where they made the Raindrops records and cut a lot of their demos. Arranger Artie Butler was a gifted young pianist and quick pencil artist whom Leiber and Stoller found working as the tape operator at Bell Sound. They hired him on the spot after watching Butler start the tape rolling in the control room and dash into the studio to play the piano and fix a part

their hired hand botched during the session. George Morton was more of an accident.

Morton knew Ellie Greenwich from Long Island and, visiting their office one afternoon at Trio Music, shot his mouth off with Jeff Barry and walked out having promised to return in a week with a hit record. Of course, he knew nothing about anything to do with hit records, but within a week, he found a group, rented a studio, hired a band, and cut a demo of a song that he wrote in his car on the way to the session. The results, which he brought to Barry a week after his first visit to their office, intrigued Jerry Leiber, who signed the screwball kid and put him to work with Barry and Greenwich. They smoothed the oddball piece into shape, ready for the studio with his group, four girls from Cambria Heights in Queens called the Shangri-Las.

An offbeat pastiche of sound effects, spoken word, soap opera narrative, arrangements from outer space, and the oddly appealing, unaffected vocals by the girls, “Remember (Walking in the Sand)” streaked into the Top Five when it was released in August, although not before another production company surfaced with signed contracts on the group who had to be cut in on the deal.

Morton, whose erratic behavior—now you see him, now you don’t—earned him the name Shadow Morton from Leiber, brought Barry and Greenwich the bones of the next Shangri-Las record, which the three of them (along with Artie Butler) hammered into “Leader of the Pack,” a massive number one hit that vaulted the two sets of sisters out of Queens into the front ranks of the day’s pop groups before they even knew how to pronounce “chateaubriand.” Barry and Morton went out and bought motorcycles.

While Barry, Greenwich, and Morton were so successfully plumbing the lucrative Top Ten teen market, Leiber and Stoller even managed a slight return to making the kind of funky records they liked, such as the starkly mordant blues “The Last Clean Shirt (My Brother Bill)” by Honeyman and New Orleans badass Alvin Robinson’s “Down Home

Girl,” a Leiber-Butler composition that featured especially witty, pungent lyrics from Leiber, although neither record was a candidate for the pop charts. Red Bird was on fire. They could put out what they wanted.