Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia (39 page)

Read Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia Online

Authors: Michael Korda

In May came news of his brother Frank’s death. Frank had been killed while leading his men forward “preparatory to the assault,” as his company commander put it in a letter to Frank’s parents, adding, in a note typical of the futility of trench warfare on the western front, “The assault I regret to say was unsuccessful.” Lawrence’s letters home after he received the news of Frank’s death are odd. Writing to his father, he regretted that the family had felt any need to go into mourning: “I cannot see any cause at all—in any case to die for one’s country is a sort of privilege.” To his mother he wrote, “You will never understand any of us after we are grown up a little. Don’t you ever feel that we love you without our telling you so?” He ended: “I didn’t say good-bye to Frank because he would rather I didn’t, & I knew there was little chance of my seeing him again; in which case we were better without a parting.” The letter to his mother makes it clear that even over a distance of thousands of miles, the old conflict between them was continuing undiminished. Clearly, despite the pain of Frank’s death, his mother was still anxious to be reassured that her sons loved her, and Lawrence was still determined not to say so. His disapproval of the fact that the family was mourning Frank and his slightly defensive tone at not having been able to say good-bye are typical of Lawrence’s lifelong effort to cut himself off from just such emotions—a kind of self-imposed moral stoicism, and a horror of any kind of emotional display. “You know men do nearly all die laughing, because they know death is very terrible, & a thing to be forgotten until after it comes,” he writes to his mother; this is neither consoling nor necessarily true. It is exactly the kind of romantic bunk about war that Lawrence himself was to dismiss in some of the more brutally realistic passages of Seven Pillars of Wisdom.

Some allowance must be made of course for the patriotic feeling and thewillingness to endure pain and death that separate Lawrence’s generation from those that followed it. These traits are exactly why Rupert Brooke’s romantic war poems seem so much harder to understand or sympathize with than the bitter, angry war poetry of Siegfried Sassoon or Wilfred Owen. Even so, Lawrence’s letters to his father and mother after Frank’s death seem harsh, and full of what we would now think of as the false nobility of war—putting a noble face on a meaningless slaughter. Frank’s own letters home are full of similar sentiments: “If I do die, I hope to die with colours flying.” This kind of high-minded sentiment about the war was shared by millions of people, including the soldiers themselves, although by 1917 it was wearing thin for most of the troops, as bitter postwar books like Robert Graves’s Goodbye to All That and Frederic Manning’s Her Privates We demonstrate. Lawrence, who would become a friend and admirer of both authors, would in the course of time proceed through the same change of heart as they did; hence the savagery, the nihilism, and the sense of personal emptiness that run through Seven Pillars of Wisdom.

*

Then, too, in May 1915, though Lawrence was in uniform, he was not fighting. However determined he may have been to be knighted and a general before he reached the age of thirty—he still had four years in which to accomplish these ambitions—he had not as yet made the first step toward active soldiering, and was beginning to feel a certain uneasy guilt. “Out here we do nothing,” he complained to his mother. “But I don’t think we are going to have to wait much longer.” This was probably not a prediction she wanted to receive with the death of one son on her mind; nor was it accurate, since almost eighteen months would pass before Lawrence was in action.

Communications between Cairo and Mecca, in 1914 and 1915, may be likened to putting a letter in a bottle and throwing it into the Hudson River in New York City in the expectation that it will eventually reach the person to whom it is addressed in London. After the message from Kitchener promising British support for an Arab state was passed on to Mecca, a long silence ensued. This was partly because communications of any kind were dangerous—contact with the British was treason—and partly because Sharif Hussein was extremely cautious. He took the precaution of sending his son Feisal to Damascus and Constantinople, to meet with Jemal Pasha, the “minister of the marine,” who had been put in charge of the campaign to attack Egypt and in general of the entire Arab population of the southeast, and with whom Feisal exchanged courtesies; and to meet more secretly with the Syrian nationalist organizations, to see whether they would support the sharif as their leader, and to try to define exactly what the borders of an Arab state should be. This was a mission that could have cost Feisal his life, but his gift for secrecy and for Arab politics exceeded even that of his elder brother Abdulla. His position, as well as that of his father and his brothers, was made more delicate by the fact that the French consul in Lebanon, François Georges-Picot, on returning to France after the declaration of war between the Allies and the Ottoman Empire, had left behind in his desk drawers a mass of incriminating correspondence with most of the major Arab nationalist figures, including messages implicating the sharif of Mecca himself. All this was now in the hands of Jemal Pasha, permitting him to play a sinister and protracted cat-and-mouse game with Arab political figures—with tragic consequences for many of those mentioned in the documents.

In the summer of 1915, after conversations with Arab nationalists who had made their way to Cairo, Sir Henry McMahon, with the blessing of Kitchener and the war cabinet, issued a declaration promising that after victory Britain would recognize an independent Arab state; for the moment, he did not define its borders. The fact that the British had unilaterally transformed Egypt, which was, in theory, part of the Ottoman Empire, into a “protectorate” with McMahon as “high commissioner” made Arab nationalists nervous about Britain’s intentions, all the more so because the French made no secret of theirs.

It was hoped that the declaration of a future Arab state would calm these fears, and perhaps persuade the Arabs to take up arms against the Turks, but all it produced was a note from Sharif Hussein to McMahon, which took almost a month to reach Cairo, and in which Hussein outlined the Arab demands for an independent state in great detail, repeating almost word for word what his son Feisal had heard in the secret talks with Arab nationalists in Damascus and Constantinople. These demands stunned McMahon. Great Britain was asked to recognize an Arab state that extended from the Mediterranean littoral in the west to the Persian Gulf in the east, and from the northernmost part of Syria to the Indian Ocean in the south (excluding Aden, which was already in British hands). In modern terms, this area would include Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Syria, Jordan, Israel, and Lebanon. Since, in the words of Hussein, “the entire Arab nation is (God be praised!) united in its resolve to pursue its noble aim to the end, at whatever cost,” an affirmative reply was requested within thirty days of receipt of the message.

To say that McMahon was taken aback by this message would be putting it mildly. For one thing, the area included a number of powerful Arab leaders who were no friends of the sharif of Mecca, including his rival ibn Saud, who was under the protection of the government of India; for another, the British themselves had designs on Iraq, where British and Indian troops were already fighting the Turks, and on Palestine, which they regarded as necessary for the protection of the Suez Canal. After consulting the war cabinet and the Foreign Office, McMahon set out to write a temporizing note—no easy task, especially given the prevailing phrasing of notes to and from Mecca. His reply begins:

To the excellent and well-born Sayyed, the descendent of Sharifs, the Crown of the Proud, Scion of Muhammad’s Tree and Branch of the Quraishite Trunk, him of the Exalted Presence and of the Lofty Rank, Sayyed son of Sayyed, Sharif son of Sharif, the Venerable, Honoured Sayyed, his Excellency the Sharif Hussein, Lord of the Many, Amir of Mecca the Blessed, the lodestar of the Faithful, and the cynosure of all devout Believers, may his Blessing descend upon the people in their multitudes!

It continues in much the same impenetrable style. The sharif’s notes, equally full of compliments, titles, blessings, and protestations of respect, are even more opaque, so that the sense has to be teased out of each beautifully crafted sentence like the meat from a nut, then parsed the way orthodox Jews parse the old Testament, repeating every sentence over and over again in search of its truest meaning.

Despite the flowery beginning, McMahon’s first message poured cold water on the projected borders of “Arab lands,” as defined by the nationalist groups in Damascus and by the sharif of Mecca. Stripped of its polite decoration, his reply was that discussion of the precise borders of an Arab state would have to wait until after victory. The sharif’s reply to this, in September, took the form of a fairly sharp rebuke, though even an admirer of his, the pro-Arab historian George Antonius, remarks that it “was a mode of expression in which his native directness was enveloped in a tight network of parentheses, incidentals, allusions, saws and apothegms, woven together by a process of literary orchestration into a sonorous rigmarole.” It was not sufficiently florid, however, to conceal the sharif’s irritation at what he describes as McMahon’s “lukewarmth and hesitancy,” which was reinforced by the arrival in Cairo of an Arab officer, Muhammad Sharif al-Faruqi, a Baghdadi, who had crossed over to the British lines at great risk to convey the fact that the sharif’s demands were essentially the same as those of the Arab nationalist groups, and not by any means those of the sharif alone.

After consulting London and his own experts, chief among them Storrs, McMahon replied on October 24 with a letter that was intended to start the immemorial Oriental process of bargaining, setting out Britain’s offer in response to the sharif’s overambitious asking price. McMahon consented this time to give Great Britain’s pledge to the independence of the Arabs within the area outlined in the sharif’s letter, but with certain important exclusions. These included the Arabs’ recognition of Britain’s “special interest” in Mesopotamia (oil); some form of joint Anglo-Arab administration for the vilayats (provinces) of Basra and Baghdad; and the exclusion of the areas to the west of Damascus, which were not “purely Arab,” in other words Lebanon, where the Druses regarded themselves as under the protection of the British and the Maronite Christians as under the protection of France. Further exclusions included—a rather broad sweep—those areas in which Great Britain was not “free to act without detriment to the interests of her ally France,” and those areas controlled by “treaties concluded by us and certain Arab Chiefs,” a polite reminder that ibn Saud and several of the sharif’s other rivals would not be included in Hussein’s Arab state. Nowhere in the letter is Palestine mentioned, unless it is meant to be included in McMahon’s guarantee that Britain would protect the holy places—by which he almost certainly meant the Muslim holy places, Mecca, Medina, and Jerusalem. On the other hand, since Palestine was not “purely Arab"—two Jewish communities were living there, one devoutly Orthodox, the other defiantly Zionist—and was indubitably to the west of Damascus, he may have meant to exclude it, or he simply took it for granted that the Allies were unlikely not to seek some form of control over the Christian holy places after the war.

T. E. Lawrence, by Augustus John.

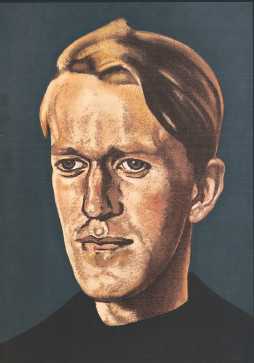

T. E. Lawrence, by Eric Kennington.