Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia (62 page)

Read Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia Online

Authors: Michael Korda

His bodyguard soon joined him there, and shortly afterward he ran into the first of Allenby’s troops, Indian cavalry troopers of the Fourth Cavalry Division manning a neatly ordered machine gun post, who at first wanted to take Lawrence prisoner. This was the first significant meeting of Allenby’s troops advancing eastward from Palestine and the Arab army marching north toward Damascus, and neither force was impressed with the other. To the British, the Arab irregulars seemed like armed and “liberated” natives running amok, while the Arabs were not impressed by the spit and polish of the Indian troopers or the severe discipline imposed on them by their officers. Lawrence remembers that when he rode on to meet Major-General Barrow, the meeting was something less than a success. To begin with, Barrow was a confirmed believer in strict discipline, who had published an article before the war in which he argued that fear of his superior officers was the best motivating force for a soldier, a point of view to which Lawrence was temperamentally opposed. Then, Lawrence thought Barrow had advanced too cautiously, stopping to water his horses too often, and saw no reason why Barrow should think it was his job to take Deraa when the Arabs already had possession of it. He took a certain pleasure in the fact that the presence of his camel made Barrow’s horse “plunge and buck” as they rode together into Deraa.

Barrow’s own memory of meeting Lawrence was dramatically different. First of all, Barrow denies that he rode into town with Lawrence at all, and says they met for the first time at the railway station, opposite the sharifian headquarters. Wherever they met, Barrow was already in a state of high indignation. He was shocked by the condition of the town and the Arabs’ open looting. “The whole place,” he wrote, “was indescribably filthy, defiled and littered with smouldering cinders and the soiled leavings of loot. Turks, some dead and some dying, lay about the railway station or sat propped against the houses. Those still living gazed at us with eyes that begged for a little of the mercy of which it was hopeless of them to ask of the Arabs, and some cried feebly for water…. In all this there was nothing that was uncommon in war. But a revolting scene was being enacted at the moment when we entered, far exceeding in its savagery anything that has been known in the conflicts between nations during the past 120 years and happily rare even in earlier times.

“A long ambulance train full of sick and wounded Turks was drawn up in the station. In the cab of the engine was the dead driver and a mortally wounded fireman. The Arab soldiers were going through the train, tearing off the clothing of the groaning and stricken Turks, regardless of gaping wounds and broken limbs, and cutting their victims’ throats…. It was a sight that no average civilised human being could bear unmoved.

“I asked Lawrence to remove the Arabs. He said he couldn’t ‘as it was their idea of war.’ I replied ‘It is not our idea of war, and if you can’t remove them, I will.’ He said, ‘If you attempt to do that I shall take no responsibility as to what happens.’ I answered ‘That’s all right; I will take responsibility,’ and at once gave orders for our men to clear the station. This was done and nothing untoward happened.”

Lawrence seems to have felt that he got the best of Barrow, and thought he had confused the general by his “exotic dress and Arab companions.” Reading Barrow’s account of Deraa in the hands of the Arab army, one is not so sure. Barrow knew that Lawrence enjoyed Allenby’s confidence, but his feeling seems to have been basically that of a major-general who thinks a temporary lieutenant-colonel is not doing his job properly. As for Lawrence’s attitude toward Barrow, it may have been at least in part colored by his dislike of Indian troops; he confessed to sharing the Arabs’ disdain for them: “At least my mind seemed to feel in the Indian troops something puny and confined … so unlike the abrupt, wholesome Beduin of our joyous Army,” he wrote. But his “joyous Army” was busy looting and cutting the throats of the Turkish wounded, and what Lawrence dismissed as “subservience” may merely have been the behavior of trained, professional troops who knew the meaning of the phrase “good order and discipline.” However, allowance should probably be made for what Lawrence had gone through in the past forty-eight hours.

Years later, after the war, when Barrow and Allenby were chatting in the study of Allenby’s London house, Allenby, according to Barrow, “tapped

The Seven Pillars of Wisdom

in his bookshelf and said: ‘Lawrence goes for you in his book, George.’ I replied to the effect that I was not taking any notice of it, and he said, ‘No, that would be a mug’s game. Besides, we know Lawrence. He thinks himself a hell of a soldier and loves posturing in the limelight.’ “ Of course we have no way of knowing if this conversation took place in exactly those words, or the degree to which Allenby was merely putting Barrow, a fellow general who was a guest in his home, at ease; but one suspects it is another example of the fact that Lawrence’s dislike of regular soldiers was reciprocated to some degree by most of them, and that even Allenby’s unwavering support may have faded ever so slightly after the taking of Damascus.

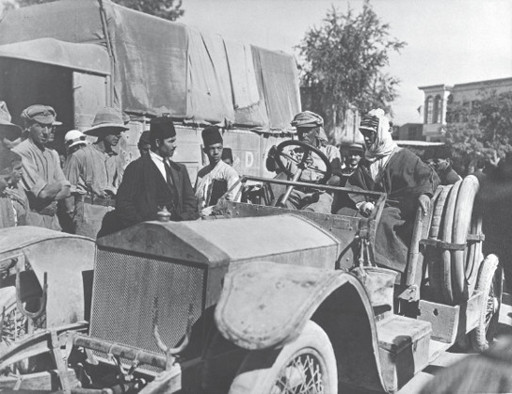

In any case, the conversation between Barrow and Lawrence at the railway station in Deraa set the tone for the future relationship between the British and Arab armies now that they had at last met east of the Jordan. Lawrence left Deraa and camped out in the open for the night with his bodyguard, for the last time; then at dawn he set out for Damascus in his Rolls-Royce with Major W. F. Stirling, who was wearing khaki and an Arab headdress. The road was blocked by Barrow’s rear guard, so Lawrence had Rolls, his driver, take the car to the old French railway, from which the Turks had stripped the rails, and they drove over the gravel ballast as fast as they could. At noon, Lawrence saw Barrow and his staff watering their horses, so he switched from the Rolls-Royce to a camel and rode over to annoy Barrow further. Barrow, it seemed, had expressed the natural belief of a cavalryman that the horse travels faster than the camel, and was astonished to see that Lawrence’s camel had caught up with him. He asked when Lawrence had left Deraa. “I said, ‘This morning,’ and his face fell. ‘Where will you stop tonight?’ was his next question. ‘Damascus,’ said I gaily and rode on, having made another enemy."

*

Lawrence was perfectly right about that. Barrow would not forget him, and since he survived Lawrence long enough to serve in the Home Guard in 1940, and did not write his memoirs until the end of World War II, he managed to have the last word. In any case, Lawrence was about to infuriate a good many more people on his way to Damascus, and after he arrived there.

Lawrence continued to be irked by the methodical advance of Barrow’s division, with forward scouts and a cavalry screen thrown out in the regulation positions, since he had been told there were no cohesive Turkish forces between here and Damascus—information which, even if he considered it true, he apparently did not pass on to Barrow. That it was actually

not

true seems borne out by the fact that about halfway to Damascus Lawrence found Nasir, Nuri Shaalan, Auda, and their tribesmen attacking a large column of Turks, who were putting up an orderly resistance. Since the Turks had mountain guns and machine guns, Lawrence drove back to seek support from Barrow’s leading cavalry regiment. He encountered an “ancient, surly” colonel of the Indian army who very reluctantly “upset the beautiful order of his march” by sending a squadron to attack the Turks, only to withdraw them when the Turks opened fire. Since he had promised the Arabs British support, Lawrence was furious, and turned back to find one of Barrow’s brigadier-generals, who sent in the horse artillery and the Middlesex Yeomanry, which succeeded in making the Turks abandon their guns and transport, and stream into the desert. There, “Auda was waiting for them, and in that night of his last battle against the Turks the deadly old man killed and killed, plundered and plundered, captured and captured, till dawn came and showed him his work was finished.” These were the last remnants of the Turkish Fourth Army, and when Auda had put an end to them, all meaningful Turkish resistance from Damascus south ceased.

Lawrence spent the night in Kiswe, only a few miles from Damascus; and the next day he consulted with Nasir and Nuri Shaalan, and “decided to send the Rualla horse galloping into town,” to alert Feisal’s supporters and Ali Riza Pasha, the governor of Damascus, who was a secret supporter of Feisal’s, that the Arab army was on its way. Allenby had told Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Chauvel, who commanded the Desert Mounted Corps, to let the Arabs go into Damascus first if possible, and with that in mind Chauvel had ordered the Australian Mounted Division to swing around the city and cut the railway line leading to Aleppo in the north and to Beirut in the west. During the day British and Arab forces mixed together outside the city, and Lawrence was anxious that an Arab government should be in place before any British troops entered Damascus. That night he succeeded in sending another 4,000 mounted tribesmen into the city, to support the Rualla sheikhs; then he waited, sleepless, through a breathlessly hot night, illuminated by fires and explosions in Damascus as the Germans blew up their ammunition dumps and stores. At dawn he drove to a ridge and looked out over the city, afraid that he would see it in ruins. Instead, he saw a green oasis of silent gardens shrouded in early morning mist, with only a few columns of black smoke rising from the night’s explosions. As he drove down toward the city, through green fields, a single horseman galloped up the road toward him. Seeing Lawrence’s head cloth, the horseman held out “a bunch of yellow grapes, shouting: ‘Good news: Damascus salutes you,’ “ and told him that his friends held the city.

Lawrence had urged Nasir and Nuri Shaalan to ride into the city before him. He was then temporarily halted by an importunate Indian army NCO who attempted to take him prisoner, and finally drove into Damascus along the long boulevard on the west bank of the Barada River toward the government buildings. People were packed solid along the road, on the pavement, on the roofs and balconies of the houses, and at every window. Many shouted Lawrence’s name as they glimpsed the small Englishman in a dark cloak and a white robe and headdress with a golden

agal,

seated beside his driver in the dusty open Rolls-Royce. “A movement like a breath, in a long sigh from gate to heart of the city, marked our course,” Lawrence wrote, and it was perhaps the proudest moment of his life, the culmination of what had begun just two years earlier when he set out to meet Feisal in the desert.

Whatever pleasure Lawrence may have allowed himself to feel at the taking of Damascus, or at the cheers from those in the crowds who recognized him, was soon erased by the scene that met him at the town hall. The building was mobbed by people dancing, weeping, and shouting for joy; but once he had pushed his way inside to the antechamber, he found a noisy chaos of political rivalry and old feuds boiling over. The leading figures among the Damascenes and the Bedouin were seated at a crowded table, with their followers behind them, all of them armed, all in furious dispute. Seated at the center of the table was Lawrence’s old enemy Abd el Kader and his brother Mohammed Said, on either side of the respected old anti-Turk hero Shukri Pasha el Ayubi, who had been arrested and tortured by Jemal Pasha in 1916. Abd el Kader was shouting at the top of his voice that he, Shukri, and his brother had formed a provisional government and proclaimed Hussein king of the Arabs, even though until yesterday the brothers had been with the Turks. The two brothers had brought their Algerian followers with them and used them to break into the meeting and seize control of it.

*

Since Lawrence believed that Abd el Kader had betrayed his attempt to destroy the bridge over the Yarmuk and also given the Turks a description of himself that had led to his being stopped at Deraa, he was infuriated; but before he could do anything about it, a furious fight broke out in front of the table, chairs went flying, and a familiar voice shouted in such violent rage that it silenced the whole room. In the center of an angry mob of their followers Auda Abu Tayi and the Druse chieftain Sultan el Atrash, old enemies, tore and clawed at each other until Lawrence “jumped in to drive them apart.” Sultan el Atrash was pushed into another room, while Lawrence dragged Auda, “blind with rage,” into the empty state room of the town hall. Sultan el Atrash had hit Auda in the face with a stick, and Auda was determined “to wash out the insult with Druse blood.” Lawrence managed to calm Auda down, and to hustle Sultan el Atrash out of town. He then decided to make Shukri the temporary military governor of Damascus until Ali Riza Rejabi returned and Feisal arrived and sorted matters out. When he announced this to Abd el Kader and his brother, they “took it rather hard, and had to be sent home,” though not before Abd el Kader “in a white heat of passion” had lunged at Lawrence with a drawn dagger, only to be stopped from using it by the intervention of Auda. Lawrence briefly contemplated having the two brothers arrested and shot, but decided that it would be a mistake to begin Arab rule in Syria with a political execution. The entire town was now in a combination of frenzied celebration and open political agitation, with the two brothers and their Algerian followers clearly bent on seizing control before Feisal or the British reached Damascus.