Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia (66 page)

Read Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia Online

Authors: Michael Korda

Those in charge of Britain’s foreign and colonial affairs were suddenly faced with a range of issues more serious and pressing than the Middle East. What was to be the future of Germany? What was to replace the defeated Austro-Hungarian Empire, which was already beginning to crumble into a number of small, mutually hostile would-be states? Who was to receive the German colonies in Africa, and on what terms? Could a viable European peace be constructed without the participation of the Russians, now controlled by a Bolshevik regime that repudiated all treaties and preached universal revolution? Clamorous advocates for new states like Poland and Czechoslovakia were already appearing, maps and draft constitutions in hand; in the Balkans the Romanians were already demanding almost a third of Hungary as their reward for joining the Allies; the Serbs, on whose behalf the war had begun, were greedy to seize as much territory as possible and create a multinational Yugoslavia; and Zionists were pressing for the rapid implementation of the Balfour Declaration.

More important than all these problems was the fact that the president of the United States was planning to join in the peace talks himself, bringing with him a host of unwelcome ideas, including a “general association of nations.” The New World was embarking on an effort to remake and reform the Old. “Even the Good Lord contented himself with only ten,” Clemenceau grumbled, when he read Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points with the skeptical eye of an old-fashioned French nationalist who already knew what he wanted: Alsace; Lorraine; the Rhineland; formidable, crippling reparations; client states in the east to hold Germany in check; and, of course, last but not least, Syria, Lebanon, Mosul with its oil, and a share in the Holy Land.

At the same time, the prospect of President Wilson’s participation in the peace talks, together with a formidable American delegation,

*

made his majesty’s government more inclined to collaborate with the French. Only by standing together, arm in arm,

bras dessus, bras dessous,

could the two principal European powers hope to resist what they both saw as Woodrow Wilson’s starry-eyed idealism and naïveté.

In the meantime, reports and advice on the Middle East continued to pour in to the Eastern Committee. Both Clayton and Hogarth sent long, detailed recommendations, basically echoing Lawrence’s views. They were quickly countered by an equally long memorandum from Sir Arthur Hirtzel of the India Office, outlining the views of the government of India. These amounted to a sharp reminder that what really mattered was the oil deposits of Mesopotamia, rather than the Syrian Desert, and a warning that it was not worth jeopardizing British interests in Mesopotamia for the sake of nebulous promises that may have been made to Hussein and his sons. Hirtzel expressed polite scorn for Lawrence, whose contempt for the Indian government and the Indian army on his brief visit to Baghdad in 1916 during the siege of Kut had not been forgotten or forgiven: “Without in the least wishing to deprecate [Lawrence’s] achievements and his undoubted genius, it must be said about him that he does not at all represent—and would not, I think, claim to represent—the local views of Northern Mesopotamia and Iraq; of the latter, indeed, he has practically no first-hand knowledge at all.”

Hirtzel also warned strongly against Lawrence’s proposal to place one of Hussein’s sons on a throne in Baghdad as king of Iraq, and another on a throne in Mosul to rule over the Kurds,

*

and suggested that if Britain raised objections to France’s ruling over Lebanon and Syria, the French would hardly be likely to accept British rule over Iraq.

Even the joy of victory did not prevent Stéphen-Jean-Marie Pichon, the French foreign minister, from administering a sharp rap on the knuckles to the British Foreign Office, reminding them that so far as France was concerned, the Sykes-Picot agreement was still in force and that France expected to receive everything it had been promised. Pichon reminded the British Foreign Office of France’s “historic duty towards the peoples of Syria,” just in case the members of the Eastern Committee had forgotten, or might have plans to denounce the Sykes-Picot agreement to President Wilson as exactly the kind of secret diplomacy that the Fourteen Points were intended to prevent.

Much as the British might deprecate the exaggerated territorial claims of King Hussein, or the ambitions of Syrian nationalists, when it came to the Middle East there was more sympathy for the Arabs in London—partly because of Lawrence—than for the French. Lawrence’s capacity for communicating enthusiasm was now concentrated on the task of getting Feisal to the Peace Conference, despite strong French opposition.

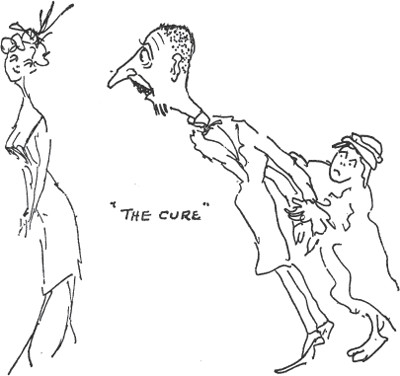

European diplomacy: A diminutive Lawrence tries to restrain Feisal from being tempted by France at the Peace Conference. Cartoon by Sir Mark Sykes.

In this, he succeeded triumphantly. By November 21, when he attended the next Eastern Committee meeting, Feisal’s participation was now considered indispensable by most of the members. “You do not want to divide the loot,” Jan Smuts warned the committee; “that would be the wrong policy for the future.” What Smuts meant, of course, was that the British should not be

seen

to be dividing the loot, least of all in cooperation with the French. They should, in the words of Curzon, “play [Arab] self-determination for all it was worth … knowing in the bottom of [their] hearts that we are more likely to benefit from it than anybody else.” Lord Robert Cecil argued for the presence of a friendly Arab prince and felt “it was essential that Feisal and the British government have the same story.” This carried the implication that Lawrence, the only person who knew Feisal, should be present to coach his friend on a common “story,” one that would—it was hoped—satisfy the Americans without alarming the French.

*

From November 8 to November 21, Lawrence had not only looked after Feisal’s interests but also placed himself as one of the central figures at the forthcoming Peace Conference—for by now nobody could doubt that “Colonel Lawrence” would be part of the British delegation. For a man who denied altogether having any ambition, Lawrence had played his cards as adroitly as Machiavelli.

In fact, Feisal and his exotic entourage, which included his personal slave and the newly promoted Brigadier-General Nuri as-Said, were already at sea, on board the cruiser HMS

Gloucester.

Just as Lawrence had been able, after Aqaba, to summon naval ships and airplanes when he needed them, now he had adroitly managed to have the Royal Navy deliver Feisal to Europe. This was not only proof of Lawrence’s prestige, but a very visible statement of British backing for the Hashemite family and its pretensions. Unfortunately, this move had not been announced to the French government, perhaps owing to a failure of communication, perhaps by an oversight, or more likely because nobody wanted to take responsibility for doing so. When the French were finally informed by their secret services that Feisal would be landing at any moment in Marseille from a British cruiser, they were predictably outraged.

Lawrence was dispatched by the Foreign Office at once to extinguish the fire, and arrived in Marseille, via Paris, with orders to smooth things down and get Feisal to Paris, or, if necessary, to London, with as little fuss as possible. Although the French claimed that Lawrence wore his white robes to greet Feisal, this seems not to have been the case. In photographs of their meeting, Lawrence is in British uniform, but he had borrowed the Arab headdress and

agal

of a Meccan officer. He gave further offense to the French by not wearing the ribbons of a

chevalier

of the Legion of Honor or his two Croix de Guerre. He was regarded in Paris as Feisal’s “evil genius,” and as a sinister agent of the British secret services. Colonel Brémond—France’s former military representative in Jidda and Lawrence’s old bête noire—was ordered to intercept Feisal and Lawrence posthaste, and inform them of France’s displeasure. Regarding Lawrence, Brémond’s instructions were uncompromising: “You must be quite candid with Lawrence, and point out to him that he is in a false position. If he is in France as a British colonel in British uniform, we welcome him. But we don’t accept him as an Arab, and if he remains in fancy dress, he is not wanted here.”

A brief tussle took place at Marseille; the British wanted Feisal to travel directly to Paris; but the French, playing for time, had quickly arranged a leisurely tour of the major battlefields, including Verdun—no doubt to show him how much greater France’s sacrifices had been in the war than those of the Hejaz—as well as a number of factories, to impress him with France’s wealth. Lawrence accompanied Feisal as far as Lyon, where Colonel Brémond finally caught up with them. The French warning regarding Lawrence was read to them, and Lawrence, possibly choosing this occasion to return his cross of the Legion of Honor to Brémond, bowed to French pressure and left Feisal to travel on to Paris alone. Throughout this trying episode Feisal behaved with a degree of dignity and patience that won him great admiration, but did nothing to change minds in Paris about Syria and Lebanon.

The French hoped that by keeping Feisal away from Paris they could persuade the British to confirm the Sykes-Picot agreement before the American delegation arrived in Paris. The two European powers could then present President Wilson with a fait accompli on the subject of the Middle East: a British Mesopotamia, a French Syria (including Lebanon), and some sort of face-saving arrangement in Palestine that would satisfy Britain, France, and American Zionists, for in Paris and London the Jews were—mistakenly—thought to have great influence over the American delegation. In large part because of Lawrence’s skillful propaganda, the British still felt themselves under obligation to Feisal, and deeply uncom fortable with the Sykes-Picot agreement. British troops were still occupying Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine, and were stubbornly (and perhaps unrealistically) prepared to play what would turn out to be a losing hand, supporting Feisal and his father against the French.

As is so often the case in politics, unforeseeable events conspired to make Feisal’s case for an independent Arab government in Syria even less promising than it had been. While Feisal was still being kept busy touring French factories (displaying a dignified, polite, but remote smile of interest), the French prime minister, Georges Clemenceau, arrived in London on what was supposed to be a ceremonial visit. At seventy-eight, the oldest of the Allied leaders, Clemenceau was a man of great intelligence, biting wit, and ferocious energy, nicknamed

le tigre

for his savage and unforgiving political skill, whose uncompromising leadership had saved France from defeat. Stocky, powerful, speaking excellent English (in his youth he had taught French and riding for a time at a girls’ school in Connecticut), with piercing eyes and a bristling walrus mustache, his hands always clad in gray cotton gloves to hide his eczema, Clemenceau was an imposing figure, perhaps the most feared politician in France. Only the prolonged bloodletting of Verdun, the disaster of General Nivelle’s offensive, and the widespread mutinies in the French army that followed it could have brought Clemenceau back to power in 1917. Now, after victory, he was faced with making a peace that would justify or repay France’s sacrifices. Among the Allies, the only leader whom he considered his equal was David Lloyd George, but the two men loathed and distrusted each other, perhaps because they were cut from the same cloth.

Lawrence at the Paris Peace Conference, as part of Feisal’s delegation. Feisal’s Sudanese slave and bodyguard, towering over everbody else, is on the right.

As the two leaders stood together in the French embassy in London Clemenceau, who had no gift for polite small talk, and was determined to cement good relations between France and Britain before Wilson arrived, bluntly asked Lloyd George what he wanted. Lloyd George quickly replied that he wanted Mesopotamia, and all of Palestine, “from Beersheba to Dan,” as well as Jerusalem. “What else?” Clemenceau asked. “I want Mosul.” “You shall have it,” Clemenceau replied. This appeared to be a burst of generosity, but it was followed by a request for Britain’s agreement, in return, to “a unified French administration in the whole of Syria, including the inland area reserved for an independent Arab administration.”