Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia (69 page)

Read Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia Online

Authors: Michael Korda

Lawrence relaxes with Clare (seated, far right), with two of her friends, and dogs.

Clare and Lawrence, then Aircraftman Shaw, in the

Biscuit.

Clare is at the wheel.

Lawrence, at the wheel, puts the

Biscuit

through its paces at high speed, towing a water-skier

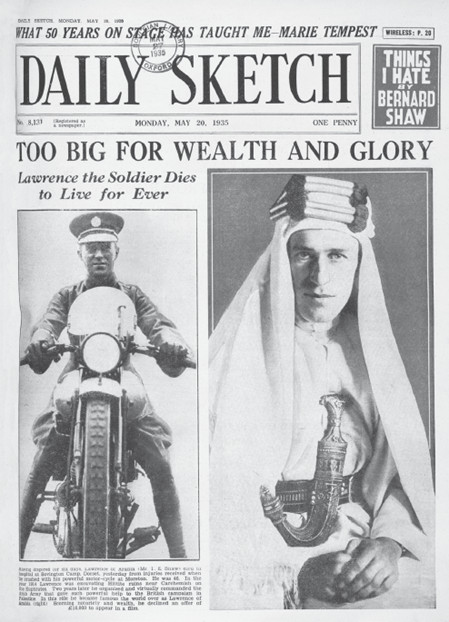

Front page of the

Daily Sketch,

announcing Lawrence’s death.

Eric Kennington’s bust of Lawrence for the memorial in the crypt of St. Paul’s Cathedral, London.

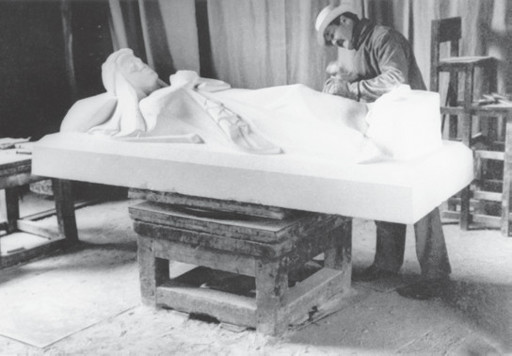

Eric Kennington works on his effigy of Lawrence.

Eric Kennington’s effigy of Lawrence, in St. Martin’s Church, Warcham, Dorset.

Lloyd George did not immediately inform the cabinet of his spur-of-the-moment gentleman’s agreement with Clemenceau, no doubt because he knew that some cabinet members would object. Nor was Clemenceau anxious to let his foreign minister, Pichon, know that he had just given away the oil of Mosul and the city of Jerusalem to the man who was known in Britain, not for nothing, as the “Welsh wizard.” Clemenceau soon came under attack from French imperialists and rightists for having betrayed France; and Lloyd George had inadvertently agreed to keep in place just those clauses of the Sykes-Picot agreement that most of his cabinet thought should be dropped or modified.

The day after this extraordinary example of impulsive personal diplomacy, Lawrence arrived back in Britain from France and went straight to see Lord Robert Cecil, to tell him about Feisal’s unfortunate reception in France. Cecil, as always sympathetic to Lawrence, immediately sent a note to Lloyd George asking him to meet with “Colonel Lawrence (the Arabian)”

[sic],

who wished to warn him of Clemenceau’s plans to undercut British and Arab aspirations in the Middle East. Because Lloyd George, unbeknownst to Cecil, had already agreed to those plans, the prime minister carefully avoided meeting with Lawrence, who was instead fobbed off with an invitation to attend his third session of the Eastern Committee, three days later. The opinion of the members was still strongly against the Sykes-Picot agreement—even Lawrence’s old opponent Lord Curzon spoke scathingly about the arrangements for Syria, describing them as “fantastic” and predicting (correctly) that they would be a source of “incessant friction between the French and ourselves, and the Arabs as third parties.”

Clearly, Curzon, like Cecil, had not yet been told of the prime minister’s bargain with Clemenceau; but A. J. Balfour apparently

had,

for to everyone’s surprise, since he seldom appeared at the committee, he spoke at length, emphasizing that Britain could not possibly repudiate the Sykes-Picot agreement, and that France’s claim to Syria and Lebanon must be respected to the letter. Balfour’s manner was famously languid and aloof, and even his friends complained that while he seemed urbane, he was ice-cold, but on this occasion he was unusually frank. If the Americans “chose to step in and cut the knot,” that was their business, “but we must not put the knife into their hand.” Balfour was foreign secretary, and while it could not be said that he enjoyed Lloyd George’s confidence, he was the senior Conservative member of the coalition government, and Lloyd George would almost certainly have revealed to Balfour what he still regarded as a coup, a triumph that gave the British everything they wanted in exchange for Syria and Lebanon, where they had nothing to gain. Those whose political instincts were sharp (and Lawrence was certainly among them) must have guessed that the government had in effect abandoned Feisal to make the best deal it could with the French.

On the other hand, the British, being British, were anxious to put a good face on things, and with that in mind the Foreign Office hastened to add Lawrence’s name to the members of the British delegation to the Peace Conference as an “advisor on special subjects,” in addition to being “a member of Feisal’s staff.” Thus Lawrence was placed in much the same ambiguous position at the Peace Conference as he had been in Arabia in 1917. Once again he was called on to manage Feisal on behalf of the British government, while at the same time attempting to secure for Feisal what he already knew Feisal wouldn’t get.

Lawrence himself would describe the postwar experience hauntingly in

Seven Pillars of Wisdom,

speaking for many of his generation who shared his bitterness: “We lived many lives in those whirling campaigns, never sparing ourselves: yet when we achieved and the new world dawned, the old men came out again and took our victory to re-make in the likeness of the former world they knew. Youth could win, but had not learned to keep: and was pitiably weak against age. We stammered that we had worked for a new heaven and a new earth, and they thanked us kindly and made their peace.”

Feisal arrived in Britain on December 10. It is not certain whether

Lawrence went to Paris to meet him, in uniform, or met him on the dock at Boulogne in his white robes, looking—according to Colonel Bré-mond—"like a choir boy” as he came down the gangplank of a British destroyer under gray skies. Since Brémond’s job, as long as Feisal was on French soil, was to stick as close to him as a watchdog on behalf of the French, it seems likely Brémond was correct.

Lawrence stayed with Feisal and his entourage at the Carlton Hotel in London, acting as Feisal’s interpreter, and dressed in a British officer’s khaki uniform, with an Arab headdress. Two days after Feisal arrived, he and Lawrence called on the foreign secretary, A. J. Balfour, to whom Feisal expressed his determination to fight the French if they tried to take control of Syria—a threat that failed to shake Balfour’s majestic calm. Later in the day Feisal had a cordial meeting at the Carlton Hotel with Chaim Weizmann, the Zionist leader who had journeyed to Aqaba to meet with Feisal in June 1918. This time Lawrence was the interpreter, and he made sure to impress on Feisal the importance of good relationships with the Zionists, especially because of American public opinion. Feisal was very conscious of this. One of the formal dinner parties in his honor was given by Lord Rothschild; and the

Jewish Chronicle

commented favorably on his meeting with Weizmann. During that meeting, Feisal had stressed his belief that there was plenty of land for Jewish settlement in Palestine, and Weizmann had said that the Jews would finance and carry out large-scale public works and agricultural improvement to the benefit of both peoples, and that as many as 4 million or 5 million Jews could settle there without encroaching on Arab land.

Lawrence and Feisal would be together in Britain for almost three weeks, during which time the government did its best to keep Feisal busy. The activities included a journey to Scotland to attend a number of “civic functions,” among them a formal visit on board the British battleship HMS

Orion,

where Feisal and Lawrence were photographed seated glumly on the deck, Feisal looking bored and dejected, and Lawrence, a tiny figure in British uniform beside him, appearing cold, and also furious at what must have seemed to him an irrelevant waste of time. The two of them are flanked and dwarfed by the ship’s captain and a rear-admiral smiling for the camera, the admiral apparently the only happy person in the group. Efforts to keep Feisal amused seem to have been no more successful in Britain than they had been in France, especially since it cannot have escaped his attention that he was being excluded from substantive discussions. The visit to Scotland was no doubt primarily intended to keep him out of London and away from the attention of journalists; this perhaps explains why he and Lawrence look more like the victims of a hijacking than honored guests.