How Soon is Now?: The Madmen and Mavericks who made Independent Music 1975-2005 (17 page)

Read How Soon is Now?: The Madmen and Mavericks who made Independent Music 1975-2005 Online

Authors: Richard King

Harper, aware that he had entered an idea in decline, scanned the Rough Trade release schedule, which by the label’s standards was looking pretty thin. ‘When I walked in, the Raincoats were about to release the

Moving

LP,’ he says. ‘They’d been there a

while. Rank and File were about to release an album. It was those two, The Fall, and that was more or less it. Distribution had that freak-show counter-culture side going on. There was a guy called Nazi Doug who had a BMW motorbike and was in Death in June. It was that lot in the warehouse and the remnants of a record company that was more or less in tatters.’

*

The early draft of Blanco y Negro’s release schedule was looking no more promising than Rough Trade’s. Despite being given the go-ahead and budget by Rob Dickins at Warners, Travis and Alway were struggling to decide on what their new label was for.

‘Rob Dickins’ attitude was, “If the two of you come together, to me, with ‘We want to sign this,’ I will do it, but if you don’t do it like that, I can’t” … it’s a perfectly reasonable attitude,’ says Alway, ‘but Geoff and I couldn’t agree on anything. I know that he thought that I lived in a bit of an ivory tower because I didn’t tend to go to gigs, and, believe me, Geoff Travis went to gigs, the guy was just everywhere. I would rather get my inspiration for records by sitting at home all evening watching

The Avengers

, that to me, was A&R, but to Geoff – you had to be on every new group and I just thought, “Well …” but there was definitely now a commercial ambition.’

Alway’s first idea for Blanco was to rehabilitate Vic Goddard, the erstwhile leader of Subway Sect who had, through a combination of over-zealous management and personal problems, fallen through the cracks after punk. Alway, who was sure Goddard still had plenty of untapped genius to release, saw Goddard as a figure for the emerging jazz and torch-singer scene that, through bands like Working Week, was becoming the soundtrack to the gradual regeneration of Soho.

‘Vic had his sort of demons at the time,’ says Alway. ‘I don’t know how to describe somebody like that, really. He was so hard

up he did demos for Geoff where he only had two strings on the guitar, and he’d be singing this song in his bedroom and you could hear his mum on the tape, going, “Vic, tea’s ready” … on the tape, “All right, I’ll be down in a minute” … and that’s what he gave us … brilliant, completely.’

Travis, who had already released Subway Sect records years earlier, was concerned that Alway, whose influences were firmly located in the daydream gauze of the Sixties, was becoming regressive in his tendencies. ‘I always wanted to have something in there that was unexpected,’ says Alway. ‘The records that inspired me were “L.S. Bumblebee”, and “I Love You, Alice B. Toklas”, which I thought was incredible. I liked all the wrong records. The Electric Prunes record I liked was

Mass in F Minor

which everybody hated, because the Prunes had been shafted by David Axelrod, but I thought David Axelrod was an absolute genius.’

Alway’s ideas for working through his inscrutable knowledge of lost psych-pop ephemera couldn’t have been further from the kind of music Travis was envisioning for Blanco’s

Warners-assisted

route to market. Travis had something much more MTV-friendly in mind. ‘Geoff wanted to sign Wet Wet Wet,’ says Alway, ‘and he wanted to sign Cyndi Lauper – and I didn’t see Blanco as the vehicle for that.’

Harper knew Alway’s habits reasonably well, and was aware that his more recherché tastes would be unable to match Travis’s more upwardly mobile ambitions for Blanco. Travis had witnessed the cold market realities of the early Eighties music business and knew what was achievable and what was going to fail. Alway, whose levels of impatience ran high, was ignoring the practicalities of running a newly formed joint venture, especially one funded by a successful no-nonsense corporate executive like Dickins. ‘Alway was busy living a fantasy world,’ says Harper. ‘He

was falling out with Geoff and Michel – Michel was just Michel in Brussels doing pretty sleeves, but Geoff and he weren’t seeing eye to eye. There were acts that Mike wanted to sign that Geoff didn’t agree with, so Mike signed them anyway.’

The result of Alway’s capriciousness meant The Monochrome Set and Felt, whom he had brought with him from Cherry Red, would never be in position for their big Blanco-funded break. Another of Alway’s

Pillows and Prayers

stand-outs, Everything but the Girl, were about to feel the full tailwind of Travis’s new commercial instincts. All of which would pass Alway by as, realising how far ahead of Travis, Dickins and Duval he’d gone, he resigned, handed back his shares in the company and retreated home to lick his wounds. Everything but the Girl’s

Eden

, a sophisticated pop record with jazz flourishes in the style Alway had envisioned for Vic Goddard, entered the charts at no. 14, the only band on

Pillows and Prayers

ever to trouble the charts, by which time Alway was long gone.

‘Geoff had played an incredibly clever game,’ says Harper. ‘He’d ended up with complete control of Blanco y Negro just as Everything but the Girl had started to become successful. It was Mike’s idea, but Geoff suddenly had it all and knew how to make it work.’

Blanco y Negro had been taking up a degree of Travis’s focus but his primary concern was still, resolutely, the future of Rough Trade, and especially the future state of the Rough Trade label.

The Blenheim Crescent address, despite its internal sense of ominous fiscal collapse, still had many positive aspects. Having survived the recent culling, it housed a leaner version of Rough Trade: a record company, The Cartel’s London headquarters, a record distribution company, a plugging and promotions company and a booking agency.

It was still the de facto international headquarters of the

independent music industry and still held great attraction to any band attempting to start a career on their own terms, which is why a new Manchester group paid the offices a visit en masse in the spring of 1983.

‘I’d been there a week or two,’ says Harper, ‘and Scott Piering was sitting there and said, “What’s Geoff’s paying you? I’ll give you another £25 and you can help me manage The Smiths.” “This Charming Man” had just come out and the whole thing had gone completely mad.’

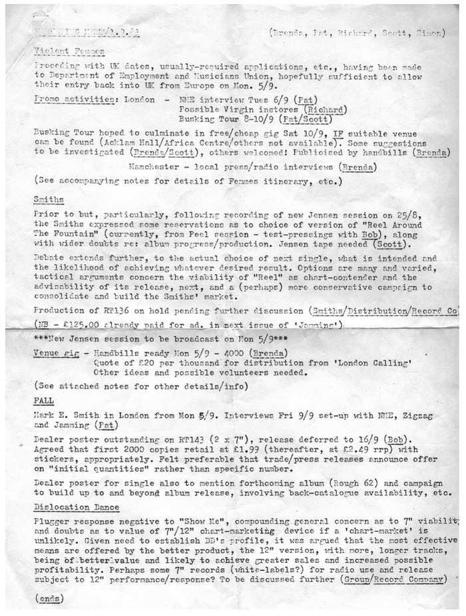

‘Wider doubts’: a memo from a Rough Trade marketing meeting on 1 September 1983 highlights the label’s internal debate about The Smiths’ commercial potential (

Cerne Canning archive

)

W

hatever the ongoing problems of Rough Trade’s finances and the factionalising of the workforce caused by Travis’s dalliance with Warner Brothers, Travis was beginning to realise that if Rough Trade had a future he would need to reconsider its purpose. It had continued to lose acts to the majors, including, in the likes of Scritti Politti and Aztec Camera, bands it had invested in beyond its means. Rough Trade’s role as an incubator for nurturing wayward talent was assured, but that was of little comfort to Travis once the talent had walked out of the door and been buffed up by his corporate rivals. Pushing his broom around the Blenheim Terrace office Travis began to realise that living and working in the moment had been a highly successful experiment for Rough Trade, but one that hadn’t guaranteed the label any future. The answer to these problems, in the form of a quartet from Manchester, was beyond Travis’s wildest dreams.

‘The great thing about Blenheim Terrace was, people could just walk in,’ says Travis, ‘and that’s what happened with Johnny and Andy. They walked in with a tape of “Hand in Glove”.’ If The Smiths benefited from the remnants of Rough Trade’s

open-counter

policy, Rough Trade would benefit far more from a quality in The Smiths that had been absent from their forbears on the label: live-or-die rock ’n’ roll ambition. ‘The Smiths were a real band,’ says Travis. ‘Morrissey might have ended up as a journalist or a writer – who knows. According to people there, Morrissey was just a lunatic around town wasn’t he? They were

in a Manchester tradition, maybe there’s a slightly different mentality there. Johnny rescued him. If Johnny hadn’t have done that who knows what would have happened to him. They saw themselves in the traditions of the Beatles, or the Stones, but most of all they were musicians.’

Joe Moss was the softly spoken proprietor of Crazyface jeans on Chapel Walks near Manchester city centre’s Deansgate. As well as running a clothing business, Moss had an encyclopaedic musical knowledge, particularly of American Sixties R&B and the auteur pop songwriters of the Brill Building – prepossessing musical styles which would leave a huge impression on one of the sales assistants from a neighbouring clothes shop.

‘I had a manufacturing business, wholesale business, and I had a couple of shops in Manchester as well,’ says Moss. ‘Johnny worked next door to one of them. I had a lot of music pictures on the wall and he introduced himself as a frustrated musician. Johnny wanted to be a musician, a professional musician, and whatever it took, he was going to do it. He was a really impressive young man.’

Moss and Marr’s insights and love of monochromatic Sixties culture encouraged the young guitarist to draw on the inspiration they were mutually discovering in the mythic past of hustlers, independent operators and outsiders as they pored over VHS documentaries and out-of-print histories of pop. The ephemeral impetus of writing a single in time for next week’s TV appearance, or the deification of the art of the girl-group song, along with permanently staying one step ahead of the entertainment industry, became a series of codes that Marr learnt by heart, as, desperate for some kind of engagement with music, he stood in any corner of where the action might be.

‘I was a sixteen-year-old walking around Manchester’, says Marr, ‘and all my waking hours were spent trying to be plugged

into the musical mains, whether it was hanging around at gigs, at rehearsal rooms, the record shops, trying to get into clubs. Within all of that, one of the most interesting things was the older, more intellectual people, who were the more radical Sixties guys who’d stuck around, making the connection with switched-on younger people.’

Manchester had its fair share of radicals with a rich vein of anecdotes and ideas to share.

Along with the Granada intelligentsia and the group around Martin Hannett’s hire company, whom Wilson affectionately called the Didsbury hacks, were luminaries from the

northwest’s

counter-cultural past, a lineage that started with the English Beats and had been reawoken by punk.

‘People like Brian Epstein appeared to be very maverick,’ says Marr. ‘I got to learn about Joe Orton, and that quality definitely resurfaced during the early Eighties. Andrew Loog Oldham was very important to me, his story and his attitude and legacy, without an understanding of which it would’ve been very difficult to just form a four-piece group out of nothing. It even made me want to make my first 45 rpm record with a navy blue label, which is what I did.’

*

The Smiths’ debut single ‘Hand in Glove’ would be dressed in the same blue livery as the mid-Sixties releases on Loog Oldham’s Immediate Records label. As well as influencing his ideas about song structure and providing a context in which to develop them, the well-heeled ideas of Loog Oldham and Orton had a definite influence on Marr’s guitar sound. Lean, plangent and mercurial in its flourishes of melody, Marr’s style, which he had worked night and day to perfect, blurred the divergence between

rhythm and lead guitar to produce a rigorously distinctive voice that was, particularly in the context of the synth-heavy Eighties, utterly unique.

‘I knew sixty Manchester bands and musicians that all played quite well,’ says Moss, ‘but I’d never heard anything like Johnny.’

Moss heard The Smiths play every day on and off for six months as the band secluded themselves in a rehearsal space on the top floor of one of Crazyface’s warehouses. Rather than play live immediately, the band wrote and rehearsed until they were able to make a note-perfect arrival. ‘They came out just ready to go,’ say Moss. ‘They really did. They had the sound absolutely down.’

The result of The Smiths’ period of isolation was that by the time they were ready to play live, their individuality was apparent from the first song. So much more than the sum of their parts, The Smiths had developed an internal logic about song craft and performance that, together with their name, meant that they stood apart from any discernible influence. The only band they sounded like was The Smiths.

As well as having an armoury of songs, Morrissey and Marr, putting the moves they had studied in Loog Oldham and Epstein into practice, started drawing up a game plan for the band which included, as a priority, the decision not to align themselves with Manchester’s newest and most prestigious company, Factory Communications.

‘The second day Morrissey and I got together,’ says Marr, ‘we laid out this manifesto. Really, it was just two young guys verbalising their pipe dreams but incredibly every one of them came true, and in that discussion we planned to sign to Rough Trade. The very fact of not signing to Factory was a statement in itself. It’s become part of the Factory story that they could’ve signed us and we tried to get a deal with them and turned them

down but that was never on the cards, I would’ve never let that happen.’

Through Morrissey the band had a connection with Rough Trade. Richard Boon, having wound down New Hormones, was on the verge of moving to London to work alongside Travis as, among other things, the editor of Rough Trade’s in-house trade magazine,

The Catalogue

. Of greater significance was a more personal connection. Linder, Morrissey’s oldest friend and confidante, had not only been Boon’s housemate but had also designed Buzzcocks’ early sleeves.

‘I could talk to Morrissey’, says Boon, ‘and he could talk to me and we did have a bit of history, having known each other around Manchester for ages. It was Linder who wanted the rented room in Whalley Range. Essentially Manchester then was a village – now it’s a 24/7 full-on city. Money didn’t used to mean anything and everyone in Manchester knew that Morrissey was going to do something but he didn’t particularly get on with Wilson. He was always sort of in the margins from that first flush of ignition of bringing the Pistols, but, within the village, he obviously wasn’t the village idiot.’

The Smiths’ decision to ignore Factory was one Moss wholeheartedly agreed with. The band’s desire to be perceived as a separate phenomenon, sharing only a superficial geographical similarity, was made plain when the band played their third-ever gig at Factory’s newly opened Haçienda. Making sure the stage was sufficiently bedecked with flowers and holding a bunch for almost the entire set, Morrissey was keen to let his fellow initiates of Manchester’s punk awakening know that an aesthetic difference was opening up between them. In one of the first pieces on The Smiths, Morrissey instantly made it clear that Factory’s design codes of minimalism and anonymity were, as far as he was concerned, a dead end. Asked why The Smiths had taken to

covering the stage in flowers he was trenchant in his response:

We introduced them as an antidote to the Haçienda when we played there; it was so sterile and inhuman. We wanted some harmony with nature. Also, to show some kind of optimism in Manchester, which the flowers represent. Manchester is so semi-paralysed still, the paralysis just zips through the whole of Factory.

The Smiths’ first appearance at the Haçienda was supporting Factory’s 52nd Street in February 1983. A few months later, in July, they headlined the club to a small crowd; after that show it would be almost another four months before The Smiths played their home town again. ‘The first time they headlined the Haçienda was the last Manchester gig that we did,’ says Moss. ‘There were about thirty people there, some of them on the floor. So we decided then that that was it. We weren’t gonna play Manchester again until we’d made it.’

Before approaching a record company The Smiths had started recording a projected first single, ‘Hand in Glove’, and contacted Boon for advice while exploring the possibility of working together.

‘I remember Morrissey saying, “Can you help?”’ says Boon, ‘and I said, “No, I’ve got no money, no resources, but I know I love it, take it to Simon Edwards at Rough Trade.”’ Spurred on by Boon’s encouragement the trip they would take down to Blenheim Crescent turned into an opportunity to hustle a record deal out of Rough Trade. Simon Edwards, who had become Rough Trade’s de facto label manager, was duly door-stepped by Marr with a cassette of ‘Hand in Glove’.

‘The myth has it’, says Boon, ‘that Simon said, “I’d really like to move this from being a distribution, M&D [manufacturing and distribution deal], one-off to the label getting involved, but Geoff’s about to leave the building.” And Johnny pins him against the wall saying, “You’ve got to listen to this.”’

Marr, channelling his inner Keith Richards, as he often had to throughout The Smiths’ career, caught Travis walking out the Blenheim Crescent door and let him know that the band were serious and Travis needed to react accordingly. ‘We went down as a band’, says Moss, ‘and Geoff didn’t want to know, but it was Johnny that forced him into having a listen. We told him that if they weren’t prepared to put it out we were going to put it out ourselves, but Geoff immediately agreed to do it, and I was straight in the booking agency part of Rough Trade and Mike Hinc organised us a gig at the Rock Garden.’

Both ‘Hand in Glove’ and its projected B-side had deeply impressed Travis. In his own considered way, having spent a weekend with the tape, he realised like Moss that the band had a rare potential for both commercial and critical success. Determined that the band should sign long-term to Rough Trade Travis began commuting to Crazyface and spending what he calls ‘long afternoons’ convincing the band of his intentions. Apart from Simon Edwards, as far as anyone at Rough Trade label or distribution was concerned, he was in a minority. There was very little enthusiasm either for the tape or for a new Manchester band at Blenheim Crescent. The misgivings of the staff were confirmed a week or two later at the Rock Garden, when the sight of The Smiths on stage, their jubilant major-key confidence and proficient musicianship on full display, was, to the bulk of the Rough Trade staff, perplexing to say the least.

‘The first time they played at the Rock Garden people from the warehouse were just totally bemused,’ says Travis. ‘It wasn’t, “Wow, listen to that song! They’re going to change the course of rock and roll!” That all came later, if it came at all.’

Among the staff at the Covent Garden show was Liz Naylor, who along with Richard Boon was part of the new staff intake at Rough Trade. As co-editor of Manchester’s witty and

vituperative

City Fun

fanzine which had critiqued the original Factory impulse, Naylor had also spent many an hour with Boon in the New Hormones office. An early resident on the Hulme estate, a modernist Sixties series of terraces that had been deserted as a result of Manchester’s overstock of council housing in the mid-Seventies, Naylor had lived in its enclave of

post-punk

bohemianism as the estates became home to A Certain Ratio and Section 25, who could live there cheaply and without interference. From her vantage point on the concrete walkways neighbouring the Russell Club site of The Factory, Naylor had witnessed the circulation of punk energy around Manchester in all its glory, and like Steven Morrissey before her had been left bemused by what she saw as Factory’s stringent aesthetics.

‘I’d never been to Cambridge and I didn’t understand the situationists,’ says Naylor, ‘and I thought Tony Wilson was in a different world, a kind of scary world where people were confident. In a way he was being post-modern before we understood what it was he was being ironic and post-modern about, and I just thought he was a wanker, purely because people were just thrown into something and we were making it up.’

City Fun

was far more supportive of The Fall and Linder’s Ludus project which Naylor and her co-editor at

City Fun

, Cath Carroll, ‘managed’. Wilson took the barbs and spite of

City Fun

in the manner they were intended, as an ongoing critique of the Factory project, determined not to let the label either run away with itself or start overstating its significance in early Eighties Manchester.

‘Manchester was very small and it was really competitive,’ says Naylor. ‘All those major industrial cities functioned a lot more coherently as post-punk, but it felt like Factory were the mill owners and we were the proletariat. You’d go to a club, this is before the Haçienda, and there’d be twenty people there, all

giving each other the evil eye because it was totally factionalised and Factory felt like a very alienating kind of project. I don’t quite see where it brought Manchester together.’