How Soon is Now?: The Madmen and Mavericks who made Independent Music 1975-2005 (20 page)

Read How Soon is Now?: The Madmen and Mavericks who made Independent Music 1975-2005 Online

Authors: Richard King

Stein in the balcony, spellbound by what was happening, was directly involved in the floral carnival. ‘I got hit in the face with one of the gladioli,’ says Stein. ‘I had a phone call from Geoff Travis, all excited about them, and I had so much trust in his judgement that I just jumped on a plane and came over and, oh God, it was amazing and … Geoff was saying to me, “Morrissey,” and I said, “It’s not just Morrissey. You’re very lucky here, this band has two superstars in it,” – and usually I’m a song person, and they certainly had the songs but even I who cared

more about songs than actually the instrumentation – you could see that Johnny was a very special guitarist.’

Having signed the band, Stein secured for The Smiths a first American date, a one-off show at Danceteria in New York; it was The Smiths’ final performance of 1983, on the last night of the year. For a band that had played only its second concert in January, their rise and their work rate had been remarkable. The band had been booked into the club by Ruth Polsky, another industry maverick who would be sufficiently smitten by The Smiths to try, unsuccessfully, to manage the band. The support act was a PA performance from Danceteria’s hat-check girl and Stein’s newest American signing to Sire, Madonna. Stein, at the utmost peak of his uptown and downtown powers, was partying on an epic scale, holding the keys to the city high in his hand, especially after dark.

‘The very first night in America, I played a very woozy set, purely because of jetlag,’ says Marr, ‘no other reason, but then I remember standing in the long, dark corridor of an underground club at half three in the morning, with Seymour saying, “I’m going to show you what New York’s all about right now,” and he did, and I thought, this is one of the things I signed up for.’

‘It just all fell into place,’ says Stein. ‘New York was so magical. I was so crazy in myself I don’t even remember it all. I was out every – every – fucking night and it was just incredible.’

Back in London, Travis and Rough Trade were coming to terms with the impact the whirlwind of The Smiths’ rise had had on the company. Unprecedented for many bands, let alone any that had been signed to Rough Trade, the scale and rapidity of The Smiths’ success was something Travis had previously dared not imagine. The band and the label would eventually define each other’s identity, but something was becoming apparent as pallet after pallet of Smiths releases got packed and dispatched

from Rough Trade. None of the other releases on the label were achieving anywhere near the amount of sales as The Smiths’ output. As Moss had predicted, the band were now in such a considerable position of authority within the company, they virtually owned it. The top-heavy relationship between Rough Trade and The Smiths would become increasingly dangerous to both their futures.

‘It was the only place for us to go,’ say Moss, ‘and I think it worked out well overall, but small businesses are volatile. It’s not just Rough Trade, it’s the nature of it. Bands like The

Go-Betweens

and The Fall all got their noses badly put out of joint, because The Smiths were the only thing keeping the place going.’

*

‘Hand in Glove’ features a harmonica intro, as does the Beatles’ debut single ‘Love Me Do’, making The Smiths’ debut a perfect homage to Loog Oldham and Epstein.

†

According to Liz Naylor, such was Kay Carroll’s distinctive presence and approach to life that, in an act of post-punk will-to-power, Cath Carroll had taken her surname.

‡

Alongside Robert Wyatt’s ‘Shipbuilding’, one of Rough Trade’s most political releases was ‘The Enemy Within’, a 12-inch by Adrian Sherwood and Keith Le Blanc. The record took its name from Margaret Thatcher’s provocative (and contemptible) phrase for Britain’s mining communities and families. All proceeds of the release went to the striking miners’ fund.

New Order,

Thieves Like Us

Fac 103 (

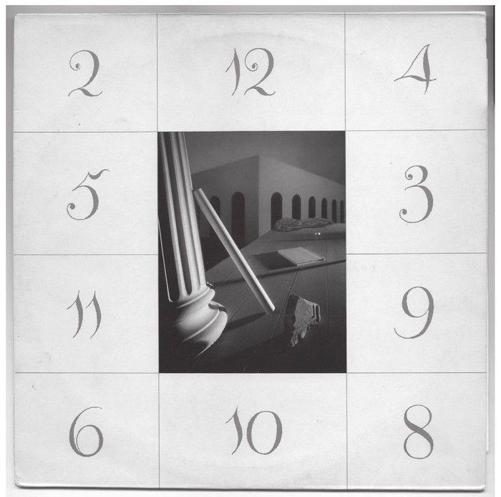

Peter Saville/Factory

)

T

he Smiths were not alone in finding New York clubs a welcoming environment for British bands. New Order and Factory were taken to the city’s heart, a relationship that would be reciprocated by Factory opening their own version of a Manhattan club in central Manchester, a decision that would both define and help ruin the company.

‘An enormous injection of cash happened,’ says Peter Saville. ‘Record sales were significant, and there was nowhere for this money to go. There was no company, no staff, no salaries, there were no offices, there was nothing, out of which came the Haçienda which was a misguided moment of idealism.’

Accompanying the steady and growing flow of money from Factory’s catalogue was an attendant accountancy black hole: running a company with an international million-pound turnover from a flat inevitably meant Factory’s paperwork was a mess. Though thriving on the sense of permanent chaos, Tony Wilson approached Rob Gretton’s wife, Lesley Gilbert, the first of many women who would manage Factory behind the scenes, to put the company’s affairs in some kind of order.

‘There was me,’ says Gilbert, ‘later on there was Lindsey Reid, Tony’s ex-wife, and then Tina Simmons took over, and Tina was a person who should’ve been there from the start because she was industry-based and super-super-efficient and on the ball. It was chaos. Although I don’t think it was really that much of a problem, records still got released, things got done.’

Tina Simmons had become familiar with Factory through working with Alan Erasmus. In contrast to Wilson’s permanent on-camera charisma and Gretton’s steeliness, Erasmus was a quiet member in the Factory partnership. Spending much of his time following up leads, Erasmus had met Simmons as a contact at one of the manufacturing companies Factory used in London, getting to know one another over the phone while trying to turn Saville’s sleeve designs into Pantone and cardboard reality.

Rather than ignoring the intricacies of Saville’s sleeve designs, Simmons had tried to accommodate them as best as possible. Impressed by her commitment and thoroughness Erasmus invited Simmons for an interview at Palatine Road where, true to form, she found Wilson, Gretton and Erasmus deep in their directorial obligations – vehemently disagreeing with one another in a haze of blue smoke.

‘It was the most bizarre interview,’ says Simmons. ‘They spent most of the time arguing amongst themselves as to why I should be there … Wilson said “There’s queues of people in Manchester wanting this job – why should I give it to you, ’cause you’re a southerner?” Everything was Manchester, Manchester.’ Wilson was outvoted and Simmons moved up to Manchester and started to try to make sense of the various strands of the Factory business.

Recently the label had set up Factory Benelux and Factory USA. Though giving the impression of international reach, the reality was an elegantly designed Factory Communications logo subtly projecting a corporate identity from some friends’ desks in Brussels and New York.

The ubiquitous Michel Duval, who had been an early partner in Blanco y Negro, along with his own Les Disques du Crépuscule label, ran Factory Benelux in Belgium. Michael Shamberg, a film-maker friend of Wilson with excellent connections in

Eighties downtown Manhattan, was nominally in charge of Factory USA in New York. Though Shamberg had easy access to all the best clubs and fun New York had to offer, there was an inherent problem with the arrangements of Factory USA that was characteristic of Wilson’s priorities.

‘Michael Shamberg set up Factory New York,’ say Simmons, ‘but the distribution and licensing was being done through Rough Trade San Francisco, so all the monies went from San Francisco into New York and then out from New York to us, or not as the case may be.’

Factory Benelux was a reasonably serious proposition. Duval’s background in sleeve design and attention to detail ensured Factory unsurprisingly gained a serious reputation in Belgium, to such an extent that many of the label’s smaller bands played to the biggest crowds of their lives in Brussels. Duval was able to operate his own release schedule featuring one-off Factory Benelux releases by the label’s roster that included New Order. While the tracks in question may have been little more than

off-cuts

or spare recordings, they were nevertheless an example of Wilson’s largesse.

In the UK with barely any promotion other than a Peter Saville sleeve appearing in the racks of the record shops, some sessions and spot plays for John Peel and a cursory announcement in the music press, New Order were effortlessly selling increasing numbers of records.

‘There were somewhere between 50–70,000 people,’ says Saville, ‘usually young men who would buy everything and

anything

that they released, so it meant that New Order could

continue

without a record company, without advertising, without promotions, without ever joining the industry, because that 50 or 60,000 sales, concentrated usually within one week of release, would force the release into the playlist, where we didn’t want it.’

New Order’s anti-career business model suited both the band and the label, allowing them to operate entirely at their own pace and within their own framework. It also validated Wilson’s ideas about the meaning of Factory. New Order entering the charts without recourse to interviews or videos featuring the band, proved its ability to be an ideas-first organisation, more a

think-tank

for a new northern creative identity rather than anything as prosaic as an indie label.

Tina Simmons arrived in 1983, after the release of New Order’s third single, ‘Blue Monday’. Had she been there as the record was being put into production she would have witnessed Factory’s working methods – an incredibly detailed sleeve, a stand-alone single release with little promotion and no attention to any of the record’s costs – blow up internationally, as the single became an enormous worldwide hit and Factory’s finances, for the first time, took a huge loss.

‘“Blue Monday” was us getting into Euro disco,’ says Stephen Morris, New Order’s drummer. ‘It was driven by Giorgio Moroder and then going to New York. It was in that kind of order and doing “Blue Monday” was trying to glue those things together.’

Immersing themselves in the production of their first album

Movement

– while an unravelling Martin Hannett tried unsuccessfully to finish the record with them – had been an introspective but productive process, one during which the band’s Bernard Sumner had changed some of his habits.

‘I guess for a long time after Ian [Curtis] died I was really depressed and sad,’ says Sumner. ‘Then I started smoking draw and I found when I was smoking draw that electronic music sounded great, and I started taking acid. Electro music:

E=MC

2

by Giorgio Moroder, Donna Summer albums, early Italian disco records – it had a wonderful effect on me. I loved the precision of it, the precise little blips.’

Recorded at the same sessions for the band’s second album,

Power, Corruption & Lies

, ‘Blue Monday’ was New Order making expressive use of precise little blips with an economy and elegance to which they added a seductive English dourness. While it might have been inspired by the erotic assertiveness of Donna Summer’s ‘I Feel Love’, ‘Blue Monday’ replaced Summer’s euphoric declaration with a question, ‘How Does It Feel to Treat Me Like You Do?’ Thanks to ‘Blue Monday’ the dance floor underwent an intervention of passive-aggressive northern introspection.

The single gained an unstoppable commercial momentum due to the combination of it being playlisted on daytime radio and it reaching a hitherto oblivious Club Med 18–30 demograph for whom ‘Blue Monday’ had become the soundtrack to their fortnight away in the sunshine, where the local Mediterranean DJs playing the song relentlessly, mixing it together with its Italian disco source material.

The single’s floppy-disk-inspired sleeve – the most widely known and purchased Factory artefact – was Saville at his most creative and innovative, incorporating the technology at the heart of the music into his design, all at a cost that ensured Factory and the band lost money on every unit sold. ‘When I finally did “Blue Monday”, the famous bone of contention, nobody at Factory saw the design,’ says Saville. ‘It went from me to the printer. Who would see it? Tony couldn’t approve it, New Order didn’t approve it. I would talk to Rob, because I felt that that was responsible. I said, “Have they seen it?” He said, “Yeah …” This was typical Rob. He said, “Hooky hates it, Stephen really likes it.” “And Bernard?” … “Don’t mind really.” And that was it.’

‘The sleeve is fantastic,’ say Morris, ‘but we were absorbed in making music, and Saville did his thing. He would mention the Futurists’ work and we just thought, “Marinetti, who’s he play for?”’

The band’s continuing disregard for the conventions of the industry were maintained throughout the run of ‘Blue Monday’ in the charts. The band insisted playing live for the supporting

Top of the Pops

appearance, a feat that put them beyond the technical expertise of the show’s engineers. The result was an awkward performance that sounded completely out of character on the programme, only adding to the band’s detached reputation.

With a single taking up residence in the Top Ten, Gretton as usual asked Richard Thomas to book them a London show. Rather than capitalising on their crossover momentum by

playing

Brixton Academy or the Town & Country club, New Order promoted ‘Blue Monday’ with a concert near Surbiton. ‘We did Tolworth Recreation Centre for “Blue Monday”,’ says Thomas. New Order may have become multiplatinum pop stars with ‘Blue Monday’, but their total indifference towards the capital only grew stronger.

While never really interested in succeeding in London, now the band, Gretton and Wilson had even turned their attention away from their home town and were spending as much time as possible in New York.

‘I got the idea for the bass drum sound on “Blue Monday” from going to Heaven,’ says Sumner. ‘Then the next step was, we went to play in New York a lot, the Fun House and Paradise Garage, and there was a New York version of that electro, Puerto Rican sound, with a gay disco influence, a mixture of dope, acid and clubs.’

‘It was very refreshing to go over there and see people having a good time with a total sense of innocence about it,’ says Morris. ‘There were no preconceptions about, it was just having a good time.’

The band at every level was absorbing the gentle sense of hedonism, the infectious thrill of the clubs. ‘We’d sleep during the day. We’d get an alarm call for half past eleven at night, meet in

someone’s room – we’d all drop a tab of acid except for Rob,’ says Sumner, ‘and Michael Shamberg would drive. We’d go to about five clubs in a night, and we’d all just go mad. Very much how E turned on people later. It happened with us with acid in 1982.’

New Order’s image also changed. The raincoats and shirt sleeves of Joy Division were replaced by polo shirts and slip-on shoes. The band now dressed with a hint of the casual or Perry Boy look; a Manchester City Eighties terrace mix of French and Italian high-end tennis clothes, polo shirts and pastel colours (although they continued to wear leather jackets as a punk badge of honour).

‘Rob always dressed like that anyway,’ says Morris. ‘He was into the casual thing, and bought shirts for us and I suppose he styled us. We had to get rid of the fucking raincoats; it was a

semi-unconscious

thing – you’re getting away from the raincoats with the music and you’re getting away from that with the clothes as well.’

The band recorded the follow-up to ‘Blue Monday’, ‘Confusion’, in New York with Arthur Baker, a producer at the heart of the city’s club scene. The video, a narrative of the song being mixed to quarter-inch tape then played in the Funhouse by Jellybean Benitez as the band, Baker and the DJ gauge the crowd’s reaction on the dance floor, is highly evocative of the New York culture in which the band and label were now immersed: kids of all races straight off the street in sneakers and high socks break-dancing to the Funhouse’s enormous bass bins.

Such a seductive environment caused ideas to ferment in Gretton, Wilson and the band’s heads. Wilson and Gretton in particular started having a series of after-hours conversations all based around the question, what if we could repeat this experience in Manchester?

‘It wasn’t straightforward,’ says Morris, ‘and it still isn’t straightforward. We got into going to clubs and doing music to

play in clubs and it had a big effect on us. Tony and Rob saw lots of big warehouse spaces and thought, “What have we got a lot of in Manchester?”’

If a combination of Factory and New Order were going to entertain opening a club, Gretton had a clear idea of whom he’d like to run it. Mike Pickering, a friend of Gretton through a shared passion for Manchester City away-days had left Manchester for Europe, odd-jobbing his way around kitchens and had settled in a large disused space in Rotterdam. ‘I met these people who’d squatted in an old disused waterworks on the banks of the river Maas,’ says Pickering, ‘and they had this big hall, Hall 4, which was full of pigeon shit, and each person that squatted there was either an artist, musician, electrician or a sound engineer.’

Hall 4 became a contemporary performance space and Pickering, using some of his Manchester connections, started booking No Wave bands who had made it out of the Lower East Side, along with some of his friends from home and the odd legend. ‘We put on loads of stuff. I don’t know how the fuck we did it to be honest. We had Captain Beefheart. Tuxedomoon lived there for a while. James White and the Blacks, Arto Lindsay and DNA – and I got a Factory night with A Certain Ratio and Section 25 and I started DJing a lot.’

Gretton, who had chosen dates in Belgium as a water-testing exercise for New Order to start performing again away from the glare of Manchester or London, was impressed by the scope of Pickering’s booking policy and its broad-church functionality.

‘Rob saw it,’ says Pickering, ‘and he said, “You’ve got to come home, ’cause I want to do a club.” So I almost immediately went back and lived with him and Lesley in Chorlton.’