How Soon is Now?: The Madmen and Mavericks who made Independent Music 1975-2005 (35 page)

Read How Soon is Now?: The Madmen and Mavericks who made Independent Music 1975-2005 Online

Authors: Richard King

*

Shellyan Orphan were the exemplar of what might be called ‘Merchant Ivory indie’. Their debut album (for which Rough Trade managed to afford Abbey Road) was named after an orchid. A notable performance by the band on

The Tube

included a string section gently playing while a painter got to work on a Cubist-style piece behind them.

†

The video for Dinosaur Jr’s single ‘Freak Scene’ was filmed in the back garden of John Robb of the Membranes’ house in Manchester, which shows that at least some of the British bands Blast First displaced were disinclined to hold a grudge.

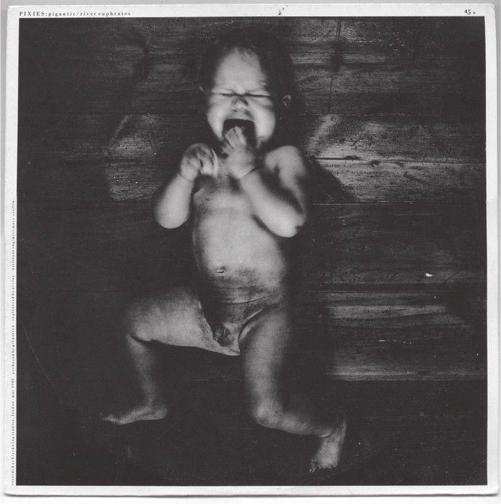

Pixies,

Gigantic

BAD 805 (

Vaughan Oliver/4AD

)

W

atts-Russell was finding the growth of 4AD more and more difficult to negotiate. Along with Vaughan Oliver and Colin Wallace, by 1987 he had a staff of around six, including his partner Deborah Edgely and Ray Conroy who managed Colourbox. With his unwavering attention to detail as focused as ever, Watts-Russell was starting to spread himself thinly over a growing release schedule. Despite employing a small workforce, he was still micromanaging every aspect of the label to ensure that its reputation and aesthetic remained intact; he was

overstretched

and increasingly reliant on his energy reserves and stress was starting to takes its toll.

‘If I was out of the office I was always in a hurry to get back to check everything was getting taken care of, and then, when I had people there to take care of everything, I kind of lost the plot,’ he says. ‘It was every day, full on. I could never get off all year, then at Christmas I wanted sun, so I went to terrible places like the Maldives. Ray Conroy somehow tracked us down to this very remote place and rang up to say that Alex Ayuli, who was later in AR Kane, at this little company called Saatchi and Saatchi, had enquired about using “Song to the Siren” in a commercial, and I said no. I got another call to say that Alex had tracked down Louise Rutkowski, who I knew and had worked with on the second This Mortal Coil album, and she was going to re-sing “Song to the Siren” for this commercial. I think I swore at him and said, “Tell her not be so fucking stupid,” but that was that,

she did it and suddenly “Song to the Siren” was in this ridiculous ad on televison. Any real knowledge of Rudy and Alex will ruin anything you think of them.’

AR Kane remain one of the most revered yet little known groups of the late Eighties. A duo of Ayuli and Rudy Tambala, AR Kane, after working with Watts-Russell, eventually released two albums on Rough Trade. The band’s music was a seductive hybrid of gently distorted guitar lines, dubbed vocals and drum machines; Ayuli, an advertising copy-writer, is credited with inventing the phrase ‘dream pop’, which described their music perfectly. AR Kane’s songs sounded as though they had been recorded in a flotation tank. Their first release, ‘When You’re Sad’, sounded like the Jesus and Mary Chain after a health regime, its crunching feedback pop delivering a sense of beatific contentment. ‘When You’re Sad’ had been released on One Little Indian, a label owned by Mayking Records, manufacturers to the bulk of the independent industry and run by Derek Birkett.

‘I already had the One Little Indian EP and really liked it,’ says Watts-Russell. ‘Alex came to see me and said, “We’d like to do another record, but One Little Indian haven’t got any money and they keep stringing us along and we want to make a record with you.” Next thing I know, someone buzzed at reception and said, “There’s somebody from One Little Indian here to see you.” Derek was there outside with Paul White, who did their artwork, and this smiley, shaven-headed bloke who, it turns out, was Einar from the Sugarcubes. He’d been to visit me in Hogarth Road in 1981 with some Iceland collective idea. Anyway it soon became clear Derek was going to fucking hit me.’

It was a short walk from the One Little Indian premises to the Alma Road office and Birkett had arrived agitated and

mob-handed

, determined to resolve the issue of, as he saw it, 4AD having stolen one of his bands. His perception of the situation had

not been helped by AR Kane’s failure to tell him they had been in discussions with Watts-Russell. Having caught wind of what was happening, Colin Wallace mustered a response team from the 4AD warehouse, resulting in a stand-off between the two companies. It wasn’t quite the mafia power struggles of Broadway or the

back-alley

thuggery of Denmark Street in the late Sixties but as things threatened to get physical One Little Indian and 4AD started squaring up over one of the most ethereal bands of all time.

‘Derek came up,’ says Wallace. ‘All the boys in the warehouse stood in reception waiting for him, and I think Derek got a bit of a fright. His bark’s worse than his bite really. I became really good friends with Derek afterwards, but we were like, “You’re not gonna come up here and cause trouble, pal.”’

The conversation that followed was an animated debate between Birkett and Watts-Russell as the former accused the latter of pinching AR Kane. ‘Derek was furious,’ says

Watts-Russell

. ‘“You fucking don’t do that! You fucking stole my fucking band!”’ Putting the disagreement to rest, Watts-Russell signed the band for a one-off release and the vague agreement to work on a further release. AR Kane’s first release for 4AD was the

Lolita

EP. Its sleeve image was of a naked girl with a knife behind her back that perfectly captured the blissful menace of the music. It was also a premonition of the events that were to follow.

‘We did the

Lolita

EP,’ says Watts-Russell. ‘Jürgen Teller did the photo for the sleeve. They said the thing they were disappointed with at One Little Indian was that they had been promised they could work with Adrian Sherwood and they didn’t. I said, “Work with Martin Young from Colourbox, he’s much better.” That was my innocent suggestion.’

The result of the collaboration between AR Kane and Colourbox was a one-off release by M/A/R/R/S, a band name consisting of the first letter of each of AR Kane and Colourbox’s

forenames. After a bad-tempered recording session, M/A/R/R/S had managed to come up with just two tracks in the studio, ‘Pump Up the Volume’ and ‘Anitina’, along with a lingering resentment towards one another.

‘They made the record,’ says Watts-Russell, ‘and they fucking hated each other. “Pump Up the Volume” has got one guitar part by AR Kane, the B-side has got Steve programming the drums, and that’s it, that’s the extent of the collaboration. AR Kane were really happy with it, Colourbox and their manager, on the other hand, were conscious that this was going to do something.’

‘Pump Up the Volume’, a collage of beats and samples threaded together over as modern and propulsive a rhythm as a studio could produce in 1987, was the record that Colourbox had always been threatening to make. As tough and funky as anything heard on pirate radio, it had an effortless and infectious groove; its use of samples was sufficiently futuristic and visionary to ensure it sounded startlingly contemporary.

‘Colourbox came to me and said, “We don’t want ‘Anitina’ on the B-side. We don’t want it to be M/A/R/R/S,”’ says

Watts-Russell

, ‘and I said no. The reason I said no was because the Colourbox singles had come out in ’86 and ’87 and Martin had been in the studio for a year and a half. So I thought no, don’t screw it up, it’ll take him another year and a half to do the B-side. Whatever. So this war started.’

Watts-Russell, his workload stretched even further, became a mediator whose primary function was to say no to the rival factions. Caught between the two camps, Watts-Russell cut his losses and decided the single would go ahead as planned and be credited to M/A/R/R/S, ruining his four-year-old relationship with Colourbox in the process.

‘We agreed that this was going to be a joint single,’ says

Watts-Russell

. ‘I fell out with Colourbox and told AR Kane to fuck off,

because their behaviour just got dreadful; it was all just fucking awful. What happened with “Pump Up the Volume” was, we were a staff of five or six and I saw the impact it had on my employees – that they loved it. They loved the fact that they could be on the phone to contemporaries of theirs in the industry and say how great, excited and jealous or whatever they were. It was Rough Trade’s first-ever no. 1, and I was really proud of that, but it was the closest I ever got without drugs to a nervous breakdown.’

Upon its release ‘Pump Up the Volume’ instantly connected; as a white label it caught fire in the clubs and began picking up plays on daytime radio. Demand was growing to the point where 4AD, whether it wanted to or not, was poised to have its first hit single.

The events that followed took a drastic turn as Watts-Russell received an injunction to cease production of the record. The production team of Stock Aitken Waterman (SAW) had detected a snippet of their track ‘Roadblock’ on ‘Pump Up the Volume’ and, taking their cue from small, streetwise dance labels in America, issued 4AD with a writ.

If he had disliked its methods before, Watts-Russell was now in four-square confrontation with the music industry, with a date in the law courts in the diary to remind him. To make matters worse, away from 4AD, his personal life was adding to the pressure.

‘In the middle of [me] being sued, my cat died and my dad died,’ says Watts-Russell. ‘I remember being in the car with Deborah talking to me and just screaming at her telling her to shut up. I thought I was going to lose it, because she was talking and I couldn’t hear what she was saying.’

The one bright spot on the horizon was Simon Harper, 4AD’s label manager at Rough Trade who faced the challenge of negotiating ‘Pump Up the Volume’s uneasy chart life alongside Watts-Russell and provided invaluable support. ‘Simon was on

the other end of the phone at Rough Trade going, “We’ve got to get more of these”, because it was flying. We had more injunctions arriving in but we were talking on the phone every day about stock levels. It was a great example of, just, a record taking off – there’s nothing you can do at that stage to stop it or try and make it more successful, it’s just got its own natural momentum and that was absolutely the case with “Pump Up the Volume”. It suddenly just exploded.’

‘Pump Up the Volume’ became a test case in the legality of sampling, a hitherto unknown aspect of music production as far as the entertainment laws were concerned. The single represented one of the first times the jurisdiction of using or ‘stealing’ another piece of work – via its having been sampled – would pass through the courts. What made ‘Pump Up the Volume’/4AD vs Stock, Aitken and Waterman even more

labyrinthine

and opaque was the fact that the piece of music Stock Aitken Waterman were claiming ownership of had already been taken from another source.

‘The thing SAW were trying to sue us for sampling was something they’d sampled!’ says Watts-Russell. ‘I had to go to cloisters up in the city to sit with wigged people. “Eugh Heullo!” reading a quote from Martin Young in

Smash Hits

saying something like, “We bunged ‘Roadblock’ all over it, they’d taken a bit of this track.” The judge looked down his nose over

half-moon

glasses going, “BUUNGED WOOOADBLOCK all over it!” To this day I believe in saying, if the experts are telling you for certain it’s one thing, for certain it’s not guaranteed. We’d sat with a musicologist we’d hired who confirmed that it wasn’t an infringement of a copyright and then two days later we had to go back and listen to their musicologist outline their version. So I was, “For fuck’s sake, we don’t need this. We’re settling.” We gave [£]25,000 to charity and that was the settlement.’

SAW, a very different company from 4AD but an independent label nonetheless, had shown their street smarts in knowing when to try their luck in the courts. 4AD had got off lightly: ‘Pump Up the Volume’ was almost nothing but uncredited samples.

‘We should have been sued to fuck by everybody,’ says

Watts-Russell

. ‘It was a brilliant record. Eric B and Rakim, who were sampled heavily, thought it was fine. We licensed it to Fourth and Broadway in the USA as they had a lot of the material that we’d sampled and could provide new ones. So it was a completely different version that came out in the USA, with all new samples that we got clearance for. We didn’t get one fucking sample clearance for the original one, that’s how maverick it was. This was done all the time on pirate radio in New York but no one had dared put it on the thing you actually paid money for. This was all pre-De La Soul. It was hair-raising stuff.’

While Watts-Russell’s energies had been taken up with the case, Rough Trade had had to cancel the record from its release schedule or be in contempt of court.

‘Pump Up the Volume’ had caught like wildfire then had to be withdrawn from the market place. The result was that once ‘Pump Up the Volume’ was cleared for release once more, such was the pent-up demand, the single became 4AD and Rough Trade’s first no. 1. ‘M/A/R/R/S sold, whatever, a million records,’ says Watts-Russell, who still single-handedly oversaw 4AD’s production schedule, ‘more than any records I’d ever physically handled – and we didn’t have any overstocks. Whilst I was doing production we never had any overstocks on sleeves never mind finished product.’

At Rough Trade Richard Scott was keen to mark the occasion of Distribution and The Cartel’s first ever no. 1; taciturn to the last, he also recognised that ‘Pump Up the Volume’ had opened a can of worms for both companies. ‘It was our first no. 1,’ he says, ‘and

it was more or less suicide for 4AD. We’d arranged some party in Alma Road in the pub next to their offices there. I phoned the landlord, asking how big a bottle of champagne we could buy, and he was a bit non-plussed, so I phoned Harrods and we got this enormous bottle and we couldn’t get the cork out. In the end we had to cut the top off and push the rest of it in.’

Watts-Russell’s shyness was exacerbated by the stress of the ‘Pump Up the Volume’ debacle but he managed to drag himself across the road to the Alma pub where he stood in the corner, all but absent from his own feast, staring at his shoes as the staff of Rough Trade endeavoured to toast their mutual success.

‘They all came over from the Rough Trade warehouse and someone opened this champagne bottle, this tall, big, black thing, and they must have thought I was a right tosser. I was in the middle of being sued so I went over there for five minutes. I can’t speak in front of more than about three people so I’m sure I didn’t say thanks to anyone and I certainly didn’t drink any champagne.’

In the building next door, Martin Mills had kept a watchful eye on 4AD’s unexpected and unhappy brush with the top of the charts, acting as a counsel and confidant for Watts-Russell who, he had noticed, was under considerable strain. “Pump Up the Volume” being a no. 1 independent record through Rough Trade/Cartel felt different,’ he says, ‘and it was such an explosive no. 1, as well, accompanied by a writ. It was deeply stressful for lots of different reasons: firstly, 4AD was doing something it hadn’t ever really intended to do, which was have a no. 1 single; secondly, there was the Pete Waterman writ, and thirdly there was what turned into being the fighting between the component parts of M/A/R/R/S about money. All of which led, I think, to Ivo’s eventual disillusionment with the music business. In the meantime he was getting wined and dined by majors.’