How Soon is Now?: The Madmen and Mavericks who made Independent Music 1975-2005 (40 page)

Read How Soon is Now?: The Madmen and Mavericks who made Independent Music 1975-2005 Online

Authors: Richard King

Despite the chart success of Ride, Creation was still permanently on the verge of bankruptcy. ‘Alan’s priorities on what to spend the money on were not necessarily what a bookkeeper would advise,’ says Kyllo. ‘It was absolutely hand to mouth. We were always at the edge of what we could afford to do. Our success was growing and, because of the way that cash flow works, you usually have to pay the bills before you get the money back, so when you’re growing that quickly it creates even bigger cash-flow issues.’

McGee, while never losing sight of the need to hustle licensing deals for his signings in America to pour back into Creation, was distracted by Ecstasy. He had watched in awe in late 1989 as two bands had appeared on

Top of the Pops

on the same night. Two years after Barrett had started promoting them in London when no one else would touch them, Happy Mondays were now in the charts alongside their home-town neighbours, the Stone Roses. It had been a strange journey from The Back Door to Babylon to

Top of the Pops.

‘We used to have an answerphone at Clerkenwell Road,’ says Dave Harper. ‘One of the most spectacular messages ever left on it was from Nathan McGough. He’s eating while he’s talking … going, “Harper, it’s Nathan, I’m managing the fucking Mondays now, so you better fucking pull your fucking finger out, all right?”’

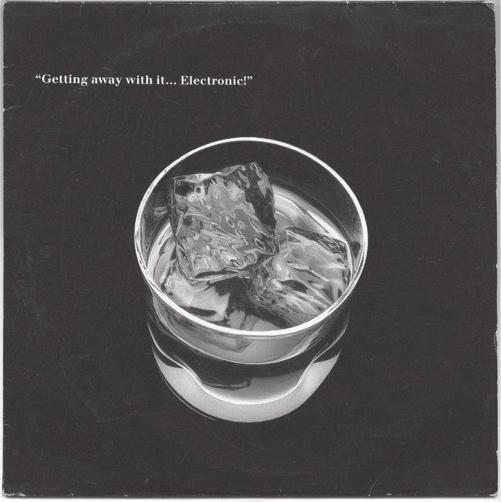

Electronic, Getting

Away With It

Fac 257 (

Peter Saville/Factory

)

A

fter the international success of

Substance

and concentrated periods of touring the US, New Order were determined that the recording of their next album should be a more relaxed affair. All four band members had agreed to start work on solo projects once the album had been completed, giving the sessions a relaxed atmosphere. Such was the leisurely mood in the camp that New Order had insisted on finding a recording studio with a swimming pool and beach access. The only residential studio that could match their criteria was in Ibiza. With perfect timing, the band arrived on an island awash with Ecstasy, and the warm pulse of Balearic beats drifting across the breeze.

‘It was a brilliant fucking holiday,’ says Stephen Morris. ‘It was a bit like going to New York the first time and seeing lofts. The only reason we went to Ibiza is because it had a swimming pool. The place was owned by Judas Priest’s drummer and it was a shit studio. We were there reading the

NME

and it’s like Balearic? That’s here isn’t it? It was kicking off – we’d seen a bit of it at Heaven but it wasn’t really a kicking off vibe.’

In Ibiza New Order experienced the relaxed energies of acid house in its Balearic, open-air, dancing-under-the stars form. They also failed to make any headway on the recording of their album and returned home with barely a drum track committed to tape. They transferred their recording sessions to the Wiltshire countryside and Peter Gabriel’s newly opened Real World Studios at Box, near Bath. New Order were Real World’s first

clients and in late 1988, for a long, almost interminable weekend, the studio was transformed into a West Country version of the Haçienda’s Hot Nights.

‘We finished the record off and Rob decided we should have a party,’ says Morris. ‘A certain group of people talk about it to this day.’

Dave Harper was summoned to the studio for what he had expected to be a playback of the album,

Technique

, and an informal discussion about plans for the release. Instead he was met with scenes of unbridled carnage. ‘I went down on the train,’ he says, ‘and there was Showsec security in the middle of Wiltshire – buses and carloads from Manchester, all of Happy Mondays and their entourage. I walked in and I can’t remember much about it. But Mike Pickering, from that day on, has referred to me as “mad dog”, because, apparently, I axed a urinal off a wall, evidently with an axe.’ ‘That was just the start,’ says Morris. ‘“Dave, Dave – what are you doing … no Dave, put the axe down.” He was pickled.’

Mike Pickering had arrived at Box in the convoy of buses and cars that had been summoned from Manchester to celebrate the album’s completion. As Haçienda regulars and members of the wider Factory circle made their way through narrow country lanes, the effects of the pills that had been swallowed in anticipation started to take hold. ‘They were double-decker coaches and everyone was getting a bit flushed,’ he says. ‘They’d obviously dropped already so they were getting a bit like, “Fucking where is it?” Someone shouted, “Lights!” We all had whistles and everyone started whistling and dancing on the bus. Then we were like, “They’re just lights, it’s just a house, it’s probably some poor old bastard in a farmhouse.” It’s a wonder we survived it really ’cause they were very strong Ecstasies, wow.’

‘The hedonism was out of control,’ says Harper. ‘When the E

hit, it was insane. At the party at Real World it was bacchanalia gone mental. I’ve been back there dozens of times over the years and never recognised the place. It was the end of the world. People didn’t recover for days on end.’

Pickering was DJing as the party reached yet another peak. As he started looking through his record box, his concentration was broken by the arrival of Graeme Park, his colleague at the Hot Nights. ‘He went, “Do you want to swap over?”’ says Pickering. ‘I went, “Fucking hell, mate, I’ve just come on.” I honestly thought I had. He went, “Mike, you’ve been playing for nearly five hours” … “Whoosh, fucking hell.” It was fucking amazing. And the best thing about it was, Peter Gabriel didn’t know.’

New Order’s first public engagement for the promotion of

Technique

was a

Top of the Pops

appearance for the single ‘Fine Time’. The track was the album’s most overt reference to the Balearic sounds they had encountered on Ibiza. Another point of reference was the single’s dichromatic sleeve – a picture of dozens of pills. The

Top of the Pops

performance was another highlight in the band’s ongoing attempts to break with the programme’s formula. After previously disastrous attempts at playing live on the show, New Order agreed to mime. As the cameras rolled, Peter Hook stood stock still with his hands in his pockets and his bass worn over the shoulder like a rifle, while Bernard Sumner danced wildly in front of the microphone. Sumner’s style of dancing would start to become familiar to television audiences as the man whose moves he had copied, Bez from Happy Mondays, followed New Order into the charts. ‘Bernard loved the Mondays,’ says Harper, ‘loved them. On

Top of the Pops

, Bernard’s wearing dungarees and he’s raving, looking insane. They’d gone mental’.

‘Fine Time’ was released in November 1988, in the same month Factory released Happy Mondays’ second album,

Bummed

. The

album was met without much fanfare. Tony Wilson scheduled the band for an appearance on his new Granada television music show,

The Other Side of Midnight

, and the band remained a lively, if little-known, phenomenon. Jeff Barrett, who was now the band’s PR man, ensured that interest was kept up, but the record’s audience, despite the cachet of a launch party at Heaven and a handful of glowing reviews, was stubbornly small.

Bummed

had a cavernous, almost whale-song, quality that left most reviewers perplexed; the fact that the promo cassette listed the first track as ‘Some Cunt from Preston’ (later renamed ‘Country Song’) only added to the general sense of apprehension around the band. Within a few months the record’s qualities would start to reveal themselves. As the proliferation of Ecstasy increased,

Bummed’

s dark energies began to take hold. Wilson had hoped that the Happy Mondays would become the rock ’n’ roll band for the Ecstasy generation and he would be proved right. But it would be a slowly evolving process before they were anointed as the raver’s Rolling Stones; and once the band had been crowned it was a position they would struggle to maintain.

‘Tony’s theory about why the Mondays failed was that there wasn’t a middle-class person in the band,’ says Nathan McGough. ‘He said the bands that always survive may have had working-class roots in them, but you need a middle-class kid in the band. They’re the ones who actually really understood the context of the band, and where it sat culturally within society. So that’s what the Mondays lacked. I guess the middle-class person within that outfit was me.’

McGough had been asked to manage the band by Shaun Ryder, a decision that had infuriated Wilson. ‘I was summoned to Tony’s house,’ says McGough, ‘and Wilson said to me, “You’re not managing this band,” and we’d been friends for, like, eight years or something. “You’re not welcome in the Factory office.

You annoy everyone …” Mike Pickering mediates at this point. And Wilson went, “Fine, right, I want a contract,” and I was like, “That’s the greatest news I’ve ever heard coming from you, because at least now you’re going to have to state what you’re going to do for the band and it’ll cost you a bit of money as well.” So we did a deal, God knows how much, but enough to get things going.’

Happy Mondays had first come to the attention of Factory through Pickering and Rob Gretton, who had seen the band perform at the Haçienda. A Factory affiliate, Phil Saxe, who later became the label’s A&R, was given the challenging task of managing them. The band’s debut LP

Squirrel & G-Man

was released in 1987 to a handful of positive reviews but little else.

*

To all concerned, even their handful of supporters, Happy Mondays appeared to be another addition to the Factory B-list, but Wilson remained committed to the band and was convinced of their potential – the largest credit on the sleeve of their 1986 single ‘Freaky Dancin” read in block Modernist capitals: ‘Executive – Antony Wilson’

†

– yet however much he liked the idea of the Happy Mondays as a street gang ready to take on the charts, he was resistant to any thought of serious investment in the group.

As Wilson’s former lodger, and as his friend and collaborator, McGough knew the Factory modus operandi intimately. He was insistent that the traditional Factory approach to marketing and PR – a combination of laissez-faire northern snobbery and

eye-catching graphic design – be re-evaluated for the Happy Mondays. ‘I told Wilson that I wanted a clean sheet and I wanted to get people focused about this band,’ he says. ‘They weren’t gonna carry on in the usual meandering Factory way, just putting it out without any promotion.’

McGough was aided in his approach by the fact the band’s artwork was produced by Central Station Design rather than Peter Saville. Two of Central Station, Matt and Pat Carroll, were cousins of Shaun and Paul Ryder, which helped the studio develop an instinctive rapport with the band’s music. Central Studio used hand-drawn, Day-Glo colours and thickly applied paints in their designs for Happy Mondays that captured the immediacy and hallucinatory energy of the recordings, giving them a vivid visual presence that was distinct from the customary detached Factory aesthetics.

All Wilson’s misgivings about McGough’s suitability to be Happy Mondays’ manager were confirmed by the choice of producer for the band’s second album; one of the few people with whom Wilson had permanently fallen out, the ex-communicated original Factory partner, Martin Hannett. Whatever Wilson thought of the situation, McGough had taken the decision based on the band’s new MDMA-enhanced music, rather than a Machiavellian desire to control Factory politics.

‘Me and Tony banged heads on a number of issues,’ says McGough. ‘The band were heavily into Ecstasy, which was really new, and I thought, well, we’re really making a kind of

drug-inspired

rock music, so it’s gonna need some kind of spatial dimension rather than just a literal recording. So I got together with Erasmus, who rang Hannett and we talked things through.’

Alan Erasmus, as he often did, mediated between Wilson and McGough. It was put to Wilson that if the differences between Factory and Hannett could be laid aside, and if the label was

prepared to demonstrate it still had confidence in the producer’s abilities, Hannett might deliver the kind of epochal recording with which he had made his name.

Still unconvinced by the idea, Wilson agreed that McGough could meet the producer in person. Rumours had circulated around Hannett in his absence from the day-to-day affairs of Factory, and little had been heard from him, other than reports of a disastrous attempt at recording the Stone Roses’ debut album. There were also whispers that his heroin use had hardened into addiction and his physical demeanour suggested that he was in poor health, the kind associated with heavy drinkers.

‘I was really shocked when I saw him,’ says McGough. ‘I’d met him when I was, like, sixteen and he was very slim, good-looking guy. He’d become about twenty-five stone, huge beard, really long hair and a massive overcoat, and he had a two-inch long fingernail, which was used as a corkscrew. Wilson was going mental about it. Anyway he sort of conceded and he kind of patched up his differences with Martin.’

For the recording Hannett had chosen a studio in Driffield, a barracks town nearly 100 miles outside Manchester where, allegedly, Happy Mondays introduced some recruits to the joys of Ecstasy. The band worked quickly and within a month the album had been finished. Any lingering resentment between Hannett and Factory was being dissolved in the producer and band’s experiments either side of the mixing desk, which to Hannett’s delight included round-the-clock doses of Ecstasy. With relations between the producer and Factory MD having thawed, even if the conversation remained a little barbed, Wilson started visiting the studio regularly. As he listened to the tracks Wilson was growing more and more animated by what he was hearing; it was the sound, he was convinced, of a new kind of drug music.

‘The big issue for me and for Wilson was a cultural one,’ says McGough, ‘because the record was made on Ecstasy. They weren’t popping four pills at a time on a Monday night – basically they’d have quarter or a half and use it as a kind of therapeutic state of mind to get into the zone, as was Hannett, so everyone was locked into making an Ecstasy vibe record.’

Wilson was familiar with the Ecstasy vibe. The band had been pivotal in acquainting the Haçienda with the drug and, by proxy, Manchester, setting in motion the club’s transformation from an empty venue-cum-hangout, into the northern equivalent of the Paradise Garage or Danceteria that he and Gretton had initially conceived. ‘The band introduced it through associated drug-dealing friends in Amsterdam,’ says McGough, ‘childhood friends of theirs. Basically, they were given a bag of 15,000 and their mates said, “Right, you knock these out.” They were the first in selling them and kind of got everything going in Manchester. The Hot Nights, on a Wednesday, were the first time you ever saw anyone with their hands in the air dancing on a podium.’

Bummed

’s dirty urban psychedelia certainly captured the

disorientating

vertigo of an Ecstasy rush. It also captured its animated euphoria. On the chorus of ‘Do It Better’, summoning every ounce of self-control he can manage under the circumstances, Shaun Ryder repeats, ‘Good, good, good, good, Double, double, good, double, double, good,’ as the band lock together over a groove that they play with a giddy instability. Although certainly an Ecstasy record, and one of Hannett’s finest productions, there was little on

Bummed

to suggest that the crowd at Hot would be dancing on a podium to Happy Mondays any time soon.