How to Be Black (9 page)

Authors: Baratunde Thurston

I

n addition to not being able to swim, black people also allegedly don't travel, but I traveled a lot during my childhood. My mother thought it was essential to mix things up, and we were constantly taking economically efficient road trips in our Nissan Datsun B210 station wagon. She loved that car and wielded it almost as if it were a part of her body. By the time I graduated from high school, we had traveled from Nova Scotia, Canada, to Disney World in it. I can only recall one plane journey in my childhood, but we moved about by Amtrak train quite often. When I was twelve, we took a nearly three-week train trip around the entire United States and deep into Mexico. In many of the places we visited, we chose highly efficient, low-carbon-footprint accommodations, also known as “camping.”

The Mexico part of that epic train journey was a trip itself. I met travel writers in Los Mochis, saw forest fires from our bus on the Mexican highway near the U.S.-Mexico border, and heard country music blasting out of a car stereo for the first time in my life. I didn't know it was even possible to blast country music! I'm not sure I thought it wasn't possible. I just know the thought had never crossed my mind before that day. I've been a changed man ever since.

All these trips, however, paled in comparison to the journey I was privileged enough to take to Senegal in the summer of 1995, just after graduating high school.

One of the French teachers at Sidwell had established a ritual of taking his students to France every summer. Joining one of these trips never concerned me since (a) I was a Spanish student, and (b) they cost a serious amount of money. My senior year, however, word spread that Monsieur Gueye

*

was not going to France that summer, but to his home country of Senegal. This got the attention of every black person associated with Sidwell, and the opportunity was the daily focus of attention in the Thurston household for months until I boarded the plane.

For me, bearing an African name, having matriculated through a West Africanâinspired rites-of-passage program, and being my mother's son, going on this trip was no choice at all. It was a duty. My mother was especially excited to go but couldn't afford to send us both, so I represented the entire family: myself, my sister, my mother, and those who came before but never got to return. I was honored, humbled, and excited! I read as much as I could in the library

*

and planned my packing list. We were told that bartering was a major form of commerce and U.S. goods could fetch a good price, so I rummaged through my clothing, toys, and other possessions identifying anything dispensable.

This was also my first foreign travel to a country that required a passport, and in the process of applying we discovered a

small

technical problem: my name wasn't actually Baratunde Rafiq Thurston, not legally at least. I never knew there was any issue with my name before this. As a kid, you just accept what your mother tells you, with no concern for or awareness of “paperwork” and “laws.”

But all official records still had me with my father's surname, making me Baratunde Rafiq Robinson. That just sounds so strange to me, even now. It doesn't sound like me, and it isn't. My mother located a DC lawyer to help her quickly file for an official name change based on the extensive paper trail of school records, communion documents, and other reports demonstrating that I was known as “Baratunde Thurston.” Miraculously, we were able to get me a passport with the Thurston name in time for the trip. A few vaccinations later, I was off to The Source Code of Blackness.

On July 25, 1995, our group met at National AirportâI still refuse to call it Reagan Airport; National for life!âand we took group photos and hugged the family members we were leaving behind. The girls on the trip had dressed up slightly, wearing nice shorts or slacks and solid-color tops. The guys dressed like we were going to just kick it on the stoop, as usual. We rocked oversize white Ts, baseball caps, and Timberland boots. After a quick hop to JFK Airport, we boarded Air Afrique and flew to the east, my brother to the east, my brother to the east, my brother to the east . . .

I

'm not sure just what I expected. Would there be a version of the Walmart greeter but specifically for black Americans on a roots-discovering pilgrimage? “Welcome home, brother! We have waited many years for your return! Your African name is . . .” Would there be some version of the Hollywood Walk of Fame, still-wet concrete into which we would dip our hands and feet to prove we had made the return trip? Would there be a special place in the mountains, surrounded by all the creatures of the mother continent bowing their heads in respectful celebration, and behind them a fountain from which pure, pristine, unadulterated blackness flowed?

Wow, that's not a bad idea. African nations seeking to boost tourism could probably convince at least a few American blacks that The Fountain of Blackness existed within their borders. Certainly a part of me, and perhaps all of us on the journey, was looking for something: a more tangible connection to our ancestry; a validation of our Afrocentricity; something to justify the investment in red, black, and green medallions and Black Power fists. We at least wanted some good deals on kente cloth!

Monsieur Gueye had arranged for us to stay at a downtown Dakar Sofitel Hotel with views of the city and the ocean beyond. The hotel was clean and just what you'd expect from any modern urban lodging. What I did not expect to find was a previously unheard-of flavor of CNN, called CNN International. It was like the CNN in the United States, but they seemed to engage in this peculiar activity known as “reporting” and were less focused on distracting the viewer with swooshy graphics. Don't worry. CNN International isn't easily available in the States.

We rolled around much of the capital by bus. I took photos and referred to them as “drive-by shootings,” because living in an actual crack-inspired DC war zone led me to believe this was funny.

Shot:

An armed guard stands at attention, his hands clasped behind his back and his automatic rifle slung across his chest. His uniform is a red, buttoned-up military jacket and red cap embroidered with a golden ring of fabric, plus jet-black pants, complemented by an expressionless jet-black face. Behind him lies the large, white presidential palace, separated from this black man with black pants and black gun by a wrought-iron black fence.

Shot:

Three young boys wave to us as our bus passes along an ocean-side road. They are each wearing pants of a different color: one red, one white, one blue.

Shot:

A group of women heats a large pot of water over a man-made outdoor fire. Whether their purpose is to cook food or launder clothes, I cannot tell.

Shot:

Three men sit against the wall on the edge of an outdoor market. The one nearest us exhales a piercingly lovely wail through his saxophone. Next to him a man seated on the ground strikes his mallet against the wooden bars of a xylophone. The third man plucks notes from his string instrument.

The bus stopped.

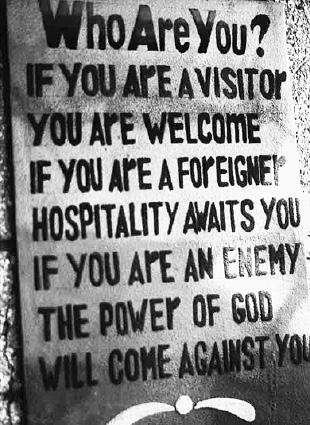

We had to hit up the small, partially indoor market crammed between two buildings on the side of the road. Parents, siblings, and distant relatives would have sent us the thousands of miles back if we didn't return with some “authentic piece of Africa” for them. We spent most of our time in the market looking at “sand paintings,” which are made from a variety of different-colored sands from across the continent to create imagery indistinguishable from non-sand paintings at a far enough distance. I froze when I saw this painted in sand:

The sand painting that purported to welcome people.

Dang! Senegalese folk have some mad dramatic welcome art! In the U.S. we just print

WELCOME

on a mat, and leave it outside our front door. West Africans invoke the wrath of God. I saw that painting, and was like, “I'm a

foreigner

and a

visitor

. I am

not

an enemy. I repeat.

Foreign

.

Visitor

.”

Shot:

My schoolmate Chip sits in the foreground. He's wearing a polo shirt and has a video camera hanging around his neck. We are on a boat. In the background is Goree Island.

Goree Island was the final point of departure for many slaves headed to the Americas and was our next major stop on the trip. Monsieur Gueye had arranged for a guided tour of the compound where wave after wave of captive Africans were housed, processed, and shipped westward across the Atlantic, if not from this exact location, then from others like it along the western coast of the continent.

Walking in the centuries-old footsteps of ancestors is probably the most humbling thing I've experienced in my life. We stood in the cramped cells. We held the weighted shackles. We looked through the infamous doorway of no return that opens directly onto the ocean and offered a one-way ticket to the afterlife for troublemaking captives. At low tide, people fell to a rocky death. At high tide, sharks, accustomed to fresh meals, awaited the occasional plunge.

This was, by far, the quietest portion of our trip. No jokes. No enthusiasm. Silence that sounded like what it was: our awe and respect.

Shot:

Our teacher, Monsieur Gueye, stands under a tree that towers above him. When he was a child he planted this tree.

One of the most enjoyable and shocking parts of the trip was our visit to Monsieur Gueye's village. The adults with us joined the village elders and talked about adult things.

We students hung out with some of the kids there, who took us on a long walk. They all commented on our appearance: “You look so old!” they kept saying to us. Apparently, for our ages, we black American kids had a Benjamin Button thing going on. We joked among ourselves that America had caused us to suffer from racism-induced early aging. After the village tour, it was time for the meal, which is always the highlight of any of my trips.

I remember one of the women of the village “introducing” us to a live chicken. He was really cute. Then she told us we had just met our dinner. I was fine with that. To this day, I count that meal of extremely fresh chicken and couscous as one of the top five meals of my life. I loved it so much I took a picture of it. I was foodspotting in 1995!

Our Senegalese journey ended with a visit to two extremely different places. The first was a resort on the coast. Again, our teacher wanted to provide us with a range of impressions. The resort was hot (physically and metaphorically). I got really excited when I found out there were nude beaches nearby, but then very unexcited when I saw it was heavily populated by fat, naked Germans. That was not the image I wanted of the Motherland.

One of the best meals of my life, foodspotted in 1995.

The last significant stop we made was a cultural center built in honor of Senegal's first president, Léopold Sédar Senghor. Senghor was the man. A noted writer, poet, cultural theorist, and politician, as we learned on the tour, he was the only African admitted to the vaunted Académie Française, a French institution that has existed for centuries as the authority on the French language. Senghor is also well known for creating the cultural-historical concept of Negritude, which sought to elevate the cultural history of Africa to the same level as that of Europe. In his own way, perhaps Senghor was living the tenets of a book we'd call

How to Be African

.

The trip had more than met my expectations. I did buy a crapload of kente cloth at amazing prices. I ate local foods. I purchased “African art.” I returned to a site of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. I dodged aggressive street vendors who were so persistent as to follow us for a

mile

. But the absolute moment of magic occurred while my friends and I were swimming in the Atlantic Ocean.

The waves were smooth and massive. I was in Africa looking west back to America, and I thought to myself, “I could die now, and be so very happy.” It wasn't that I had a desire to die. What I felt, though, was a sense of completion, satisfaction, and contentedness I'd never known before that moment. Making that journey did not make me any blacker, but it completed a circle in my life that I hadn't realized was broken until it was made whole again.